I will tell you something that most martial arts teachers and self‑defence instructors do not like to admit. Some do not even admit it to themselves.

Many of the techniques you may have learnt will not work if your attacker has a knife.

Switching to a specialised set of anti‑knife techniques is not a solution. In many knife attacks, the defender fails to see the knife before the attack. Poor lighting, crowded conditions or competent tactics by the knife-man are just some of the factors that can hide a blade.

ATACK: Assume That Attacker Conceals Knives. Treat any attack as a potential knife attack. Defend accordingly.

Whenever you learn a technique, you should be asking yourself several questions:

• Will this technique be practical if the attacker has a knife or other weapon?

•Is the attack realistic? Would it reach the defender and is the attacker maintaining a guard?

• How would I counter this technique if I was the attacker?

• Would this technique work against someone not fighting in my style or a particular style?

Today’s blog expands on an observation I made in a previous post.

I noted how frequent it was that many tai chi defensive movements presented the outer surfaces of the forearms towards an enemy.

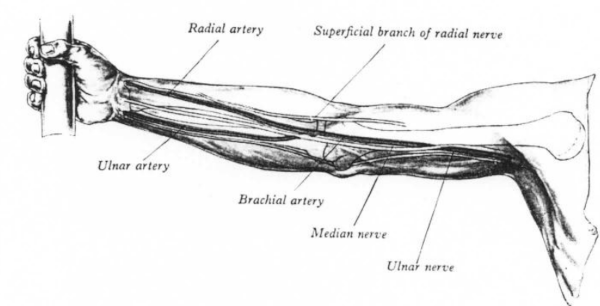

The inner side of the forearm has a deeper covering of flesh. Within these muscles are the radial and ulnar arteries and the radial, medial and ulnar nerves.

A strike to the inner forearm may numb the nerves, reducing the limb’s ability to defend or attack. A cut to the inner forearm may sever one or more arteries, resulting in a potentially fatal bleed‑out.

If you cannot avoid taking a blow or cut, taking it on the outer rather than the inner side of the forearm is preferable.

Cloth, such as your sleeves will help reduce any damage from a knife strike. If you are a law enforcement officer or in a similar role where knife attack is probable, make a habit of wearing gloves or fingerless gloves.

Here I will remind the reader that parrying actions are secondary defence techniques to evasion and avoidance. Techniques such a ginga and dodging will keep away from knives. Parries are used when evasion fails, or as a component of a counter‑attack action to control the weapon hand.

An effective parry does not just redirect an attack, but includes motions that remove potential targets from the path of the attack.

Palm-In Parrying

Many tai chi defensive movements/“postures” place the lead hand with the back of the hand toward the enemy or uppermost. This orientation protects the inner forearm area from the most likely direct attacks.

One of the most obvious example of this is peng/p’eng/wardoff. The lead arm is held curved and roughly horizontal before the body, back of the palm towards the threat. The rear arm is usually held below or behind the lead arm, often orientated so the inner forearm is protected.

In “How To Use Tai Chi As A Fighting Art”, Erle reminds us that in combat the “hold the ball” hand positioning is often made with the lower hand palm down.

combat the “hold the ball” hand positioning is often made with the lower hand palm down.

combat the “hold the ball” hand positioning is often made with the lower hand palm down.

combat the “hold the ball” hand positioning is often made with the lower hand palm down. “In this posture the harder area of the forearm is used to block [parry] the attack and so not damage the soft area of the arm.”

In other movements, such as “Grasp sparrow’s tail” we see the lead arm in a more vertical position, but once again the back of the palm and outer forearm are towards the enemy.

Parries with the outer forearm may utilize the ulnar edge of the forearm, in much the same way that parries with the palm may utilize the edges of the hand. Avoid parrying bone against bone, however.

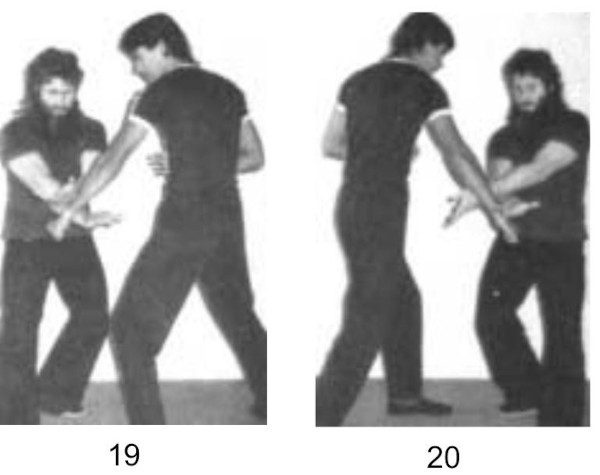

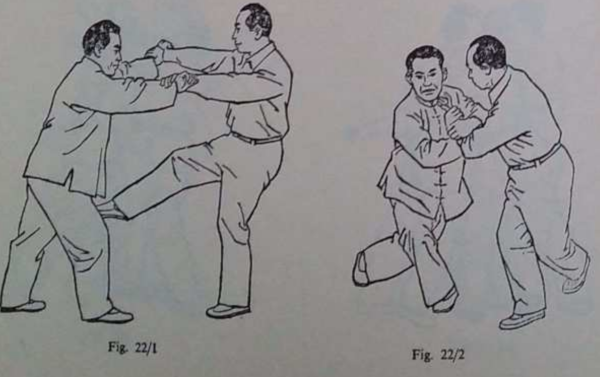

Parries from such movements are often taken with the outer forearm making initial contract. Combined with waist movement, the arm may rotate to redirect the attack. This action may result in the hand being placed palm down on the limb. This contact may be used to grab, hook, redirect, push, control or to sense the foe’s next actions.

For an example, see the illustration of the “Outside Crane” in “Attack, Avoid, Survive”. Contact is made with the back of the hand and the hand rolls to hook the fingers over the arm.

Such contacts should be transitory. Leave a hand in contact too long and the foe may try cutting it.

For those familiar with wing chun, it will be appreciated that tan/taan sau/sao is an outer forearm towards the enemy configuration.

Palm-First Parries

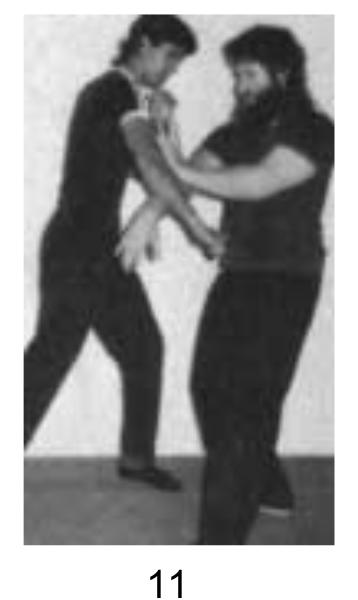

Of the tai chi movements that do not present the back of the hand, many instead make initial contact with the palm or fingertips. Many of these use an approach angle that still protects the inner side of the forearm.

Under parries with the palm, I choose to include those movements that make initial contact with either edge of the palm. This is the “knife‑hand” between the base of the little finger and wrist, and the “reverse knife hand” surface between the base of the thumb and wrist. A contact made with the edge of the hand may roll into a contact with the palm. A contact with the palm may transfer to the a palm edge.

It is also possible to employ the edges of the palm when making palm-inward actions.

Remember that palm‑first actions may be parries or strikes. In fact, the only difference between a strike and a parry is often one of context and opportunity.

One of the aspects of simultaneous attack and defence is that one body-part may attack as another defends. Another aspect is that a defence may also attack and an attack also defend.

The back of the palm is also a striking weapon. For example, from peng, either hand may deliver a potent backhand strike under the jawline to the Stomach‑9 point on the side of the throat.

Less potentially lethal, the back of the hand may simultaneously hit the points above the eye and under the cheekbone.

Quadrants of Parrying

In previous writings, I have talked about the “quadrants of defence”. Most attacks may be parried by either a inward or outward parry, and will require either a high or low level parrying action. Your parrying response thus constitutes either a rhomboid or a rectangle, depending on the fighting method you train in.

The “back‑of‑the‑hand” or “palm‑in” parries are very well suited to outward parries.

From “hold the ball” or “grasp the sparrow’s tail” the arm is easily dropped to swing outwards for a low parry or flicked up and outward against a higher attack. Because tai chi teaches you to hold your arms relaxed, such actions can be very fast and strong.

The outside of the forearm in the primary contact area, although the back of the hand may slap an attack off line. More of slapping‑style parries a little later.

Inward back‑of‑the‑hand parries may need a bit more practice.

The high inward parry may be made as a chopping action, contact area most likely being the ulnar edge of the forearm or the knife‑edge of the hand. Allow your arm to relax and power the motion by a waist twist and footwork.

The low inward back‑of‑the‑hand parry I find a little more awkward. You need a sort of combined swinging/thrusting action, with a waist twist to power it and take potential targets out of the way. This resembles the low parry of karate, but is thrust inward. A hikate action can help with the waist action.

Palm‑first parries, including knife‑hand and reverse knife‑hand actions, may either parry inward or outward. Their drawback is that using the hand rather than the forearm, the defender must be more accurate and there is a greater probability of failure.

In addition, certain palm parries will expose the inner forearm to attack. Favour palm parries that keep the outside or the forearm uppermost and/or towards the enemy.

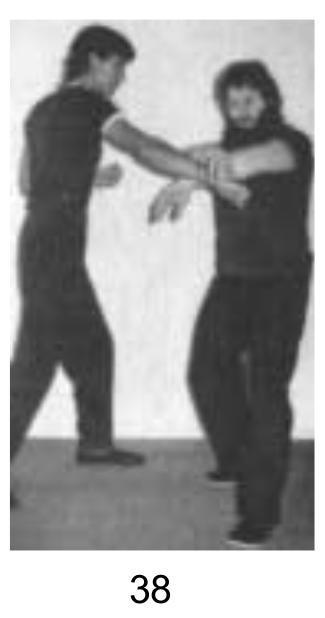

When practical, use double‑handed parries rather than single‑arm inward parries. The outward parrying arm of the pair will probably be in a back of the palm outward configuration, with the outside of forearm available to parry.

Some parrying actions that used crossed arms were described in the last post. Practice these so the outer sides of the forearms are always outward/uppermost relative to the enemy/threat.

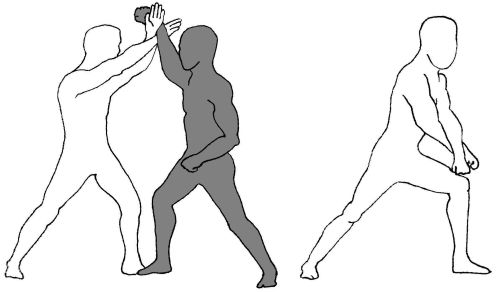

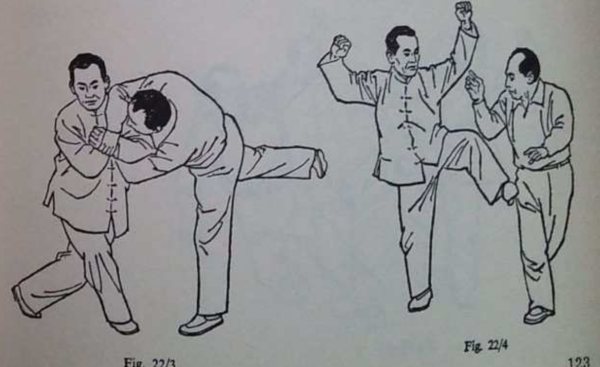

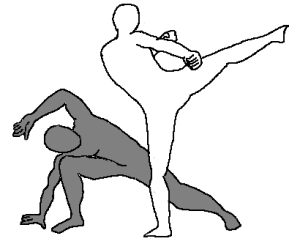

Double‑handed parries need not be made with the arms touching each other. See the illustration of an “inside crane” in my book. The rear arm makes an outward parry with the outside of the forearm and the palm inward, and the lead hand makes a knife‑hand parry with the outer forearm upwards.

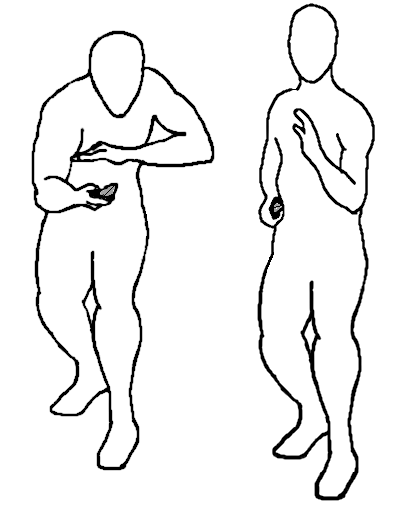

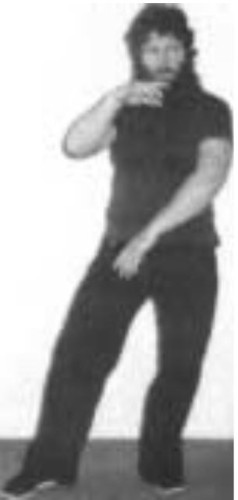

Ready stances such as boxing ready, fighting ready and p;eng hinge should be practised with the back of the hands and forearms towards the enemy.

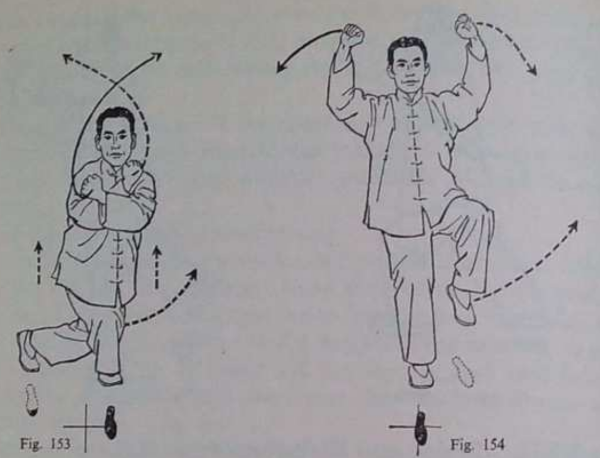

Erle is shown in a variant of p'eng hinge (above). This posture looks non-aggressive, but one arm is positioned ready to defend the upper body, the other the lower and they both may act together.

Another useful pre‑combat stance is to stand with one hand over the other, both around belt‑buckle level.

A defence against a high hooking strike is to bring your hand up to the side of your head, as though brushing back your hair (if you still have some). Ideally this action sweeps across the face on the way. This defence also utilizes the outer forearm area of the bent arm.

Commonly depicted as a blocking action, this can be made into a parry/evasion by turning toward the attack and dropping downward and moving backward. This spiralling action may be used to drive the other hand out in a counter‑strike.

This action may offer some protection against a high knife attack, reducing the severity of an injury at least.

Note that in ginga the bent arm presents the outside of the forearm towards the foe.

Whip/Slap Parries

In “Knives, Knife Fighting & Related Hassles”, Marc Macyoung recommends “whip/slap” parries. These “…originate from the wrist, using the elbow as a pivot point. One way of looking at them is, under control, you throw your wrist at an incoming strike. When done properly, the wrist will arrive at the destination the moment your arm’s motion is arrested. This allows for all of the energy to be transferred into whatever is hit.”

Striking or parrying with a relaxed or semi‑relaxed arm has obvious parallels with the tai chi techniques and principles described above.

When applied with the palm of the hand, the whip/slap parries clearly have a similarity to the tai chi palm‑first defensive moves already described. Obvious applications are as inward or downward parries.

As a parrying technique primarily using the hands, accuracy is needed as well as speed and relaxation.

The hand configuration shown in Macyoung’s book for the upwards whip parry (left) has a clear resemblance to the crane/turtle head/horse foot hand used in tai chi single whip (above). As the relaxed hand is flicked upward or outward, the wrist naturally bends and the fingers trail. Primary impact surface is the back of the hand or the wrist area.

The hand configuration shown in Macyoung’s book for the upwards whip parry (left) has a clear resemblance to the crane/turtle head/horse foot hand used in tai chi single whip (above). As the relaxed hand is flicked upward or outward, the wrist naturally bends and the fingers trail. Primary impact surface is the back of the hand or the wrist area.I have seen a clip of Erle Montaigue conducting a knife defence workshop. A student stabs at Erle, so Erle twist to face right and brings an arm up in an explosive “Paint the fence, Daniel‑san” move, hitting the underside of the knife arm. Much to everyone’s surprise, this impact against the arm knocks the knife out of the student’s hand and high up into the air.

This nicely illustrates that a whip/slap type technique may be used even if the contract area is the outer forearm rather than the wrist or hand. This action is therefore applicable to movements where the back of the hand is towards an enemy.

A parry with the dorsum of a horse foot palm is not just for rising parries. The back of the horse foot hand may be directed as an outward horizontal or oblique parry or even as a downward parry with the fingers raised upwards.

When the fingers of a horse foot hand are horizontal this resembles the fook sau of wing chun, so may be used for indexing a foe.

Elsewhere, I have discussed how the horse foot hand form may be used as a hammer‑fist, reverse hammer‑fist or a downward punch.

As a defensive technique, horse foot hand may both parry and hook over attacking limbs.

The sides of the horse foot hand, or even the knuckles, may also be used to parry/strike at an attack.

Note that these defensive moves have mainly used the palm, knife-hand and hammer-fist, the primary weapons taught in Crash Combat. To these has been added the use of the back of the hand and the forearm.

This is a further illustration of how defensive moves may be used offensively.