My gas bill this previous quarter was much higher than I expected. Made even more frightening by the fact that it was a mild winter and I had barely used the heating. This got me thinking again about ways to save energy when cooking.

A friend of mine once told me that during the rationing of World War Two his mother saved fuel by soaking rice overnight. By doing this she only needed to cook it five minutes. Time to experiment with this method again.

Here is the method that I have ironed out over the last few days:

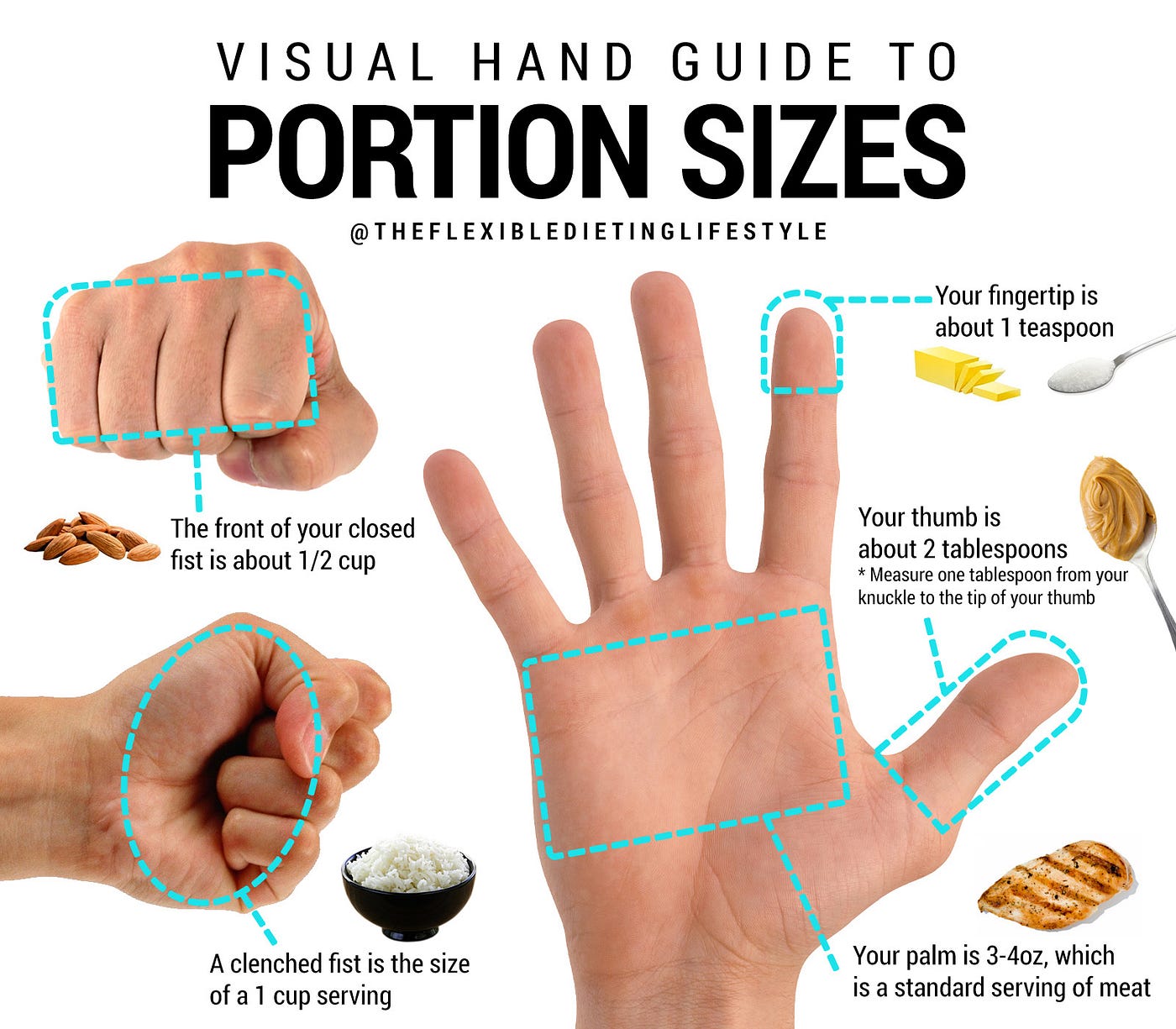

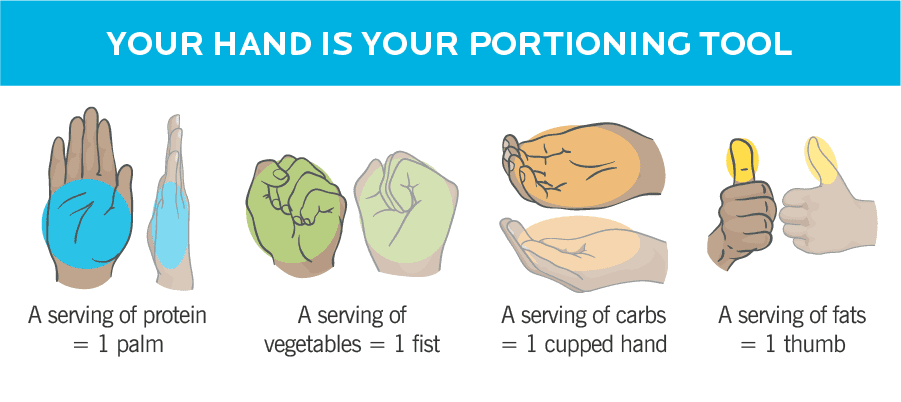

Measure out your rice. 100 g is a generous portion and comes up to the 100 ml mark in one of my measuring jugs. Rather than bothering to weight the rice, I just fill the jug to the mark.

Cooked rice is about three times the volume of dried. A quarter to half a cup of dried rice is good for a side dish. If you are hiking in the snow, a full cup may be warranted.

For this pre-soak method, I generally fill a coffee mug half to two-thirds and top up with water.

Study the apparent depth and volume of the rice so you can estimate a similar amount by eye if necessary.

Place your cup of rice and water in the fridge. The first time I tried pre-soaking rice I ended up leaving it longer than I intended since I spent the next couple of nights down the pub and eating out. The rice sort of started fermenting, so I suggest you keep the soaking rice in the fridge just in case you are delayed. If it is winter, the kitchen is generally cold enough.

Leave the rice to soak a few hours, or better still, overnight.

When it is time to cook, pour the rice and water into a pot.

A broader pot heats up quicker and is less likely to boil over. You may need to add a bit more water to the rice so it is covered by at least a centimetre of water. Add a little salt too. Use a hob of suitable size for your pot.

Cooking instructions on packets of rice generally overestimate the cooking time or quantity of water needed.

If you add too much water, you are going to waste fuel heating it up. Too little and your pot may boil dry before you are done. You will have to experiment on getting the optimum for the pot you use. As in so many things, balance is the key.

Rice needs about twice its volume in water. As a general rule of thumb, ensure the rice is under 25 mm of water. For this method using presoaked rice you will actually need less water since there will be less cooking time.

Cover your pot, bring to the boil and then turn down the heat to simmer.

Give the rice about five to seven minutes.

If you are new to this cooking method, taste a little of the rice to see if it is soft or still a little gritty.

Turn off the heat and let the pot stand, preferably over the still hot hob. The residual heat will continue to cook the rice without expending fuel. This gives you time to finish cooking the other components of your meal.

Drain your rice. Turn out onto a plate and serve with a variety of vegetables and a sensibly-sized portion of meat.

This method will prove pretty useful if you are hiking or camping and have to carry your own fuel.

In this case, I suggest that in the morning you place your rice and water in a wide-mouthed screw-top container and let it sit in your rucksack while you are walking. Such a container is a useful addition to your hiking kit since it can be used to prepare other backpacking foods that need a long soak.

I will have to experiment. Have a go yourselves.

derived from a civilian tool favoured by outdoorsmen. Hangers, “short hunting swords” or “couteau de chasse” were useful for chopping firewood, clearing brush and butchering game. They were carried by noble and commoner alike. There are exciting accounts of them being used to hunt game and they were a useful defence against both beast and man. Decorated versions might be worn out court to display one’s affection for hunting. They might also be worn in town as a handy defence against robbers, in many cases being more effective and convenient than rapiers or small swords. Understandably the common foot soldier found the hanger to be a useful implement. In addition to the sword bayonet the hanger is probably the ancestor of both the naval cutlass and the machete, and is why you occasionally come across machetes referred to as cutlasses. Sword bayonets were created to produce a bayonet that also served as an infantryman’s hanger. The yataghan configuration blade provided better clearance for the hand when reloading a muzzle-loading weapon. The blade shape is not without other merits so a number of breech loaders also used sabre bayonets.

derived from a civilian tool favoured by outdoorsmen. Hangers, “short hunting swords” or “couteau de chasse” were useful for chopping firewood, clearing brush and butchering game. They were carried by noble and commoner alike. There are exciting accounts of them being used to hunt game and they were a useful defence against both beast and man. Decorated versions might be worn out court to display one’s affection for hunting. They might also be worn in town as a handy defence against robbers, in many cases being more effective and convenient than rapiers or small swords. Understandably the common foot soldier found the hanger to be a useful implement. In addition to the sword bayonet the hanger is probably the ancestor of both the naval cutlass and the machete, and is why you occasionally come across machetes referred to as cutlasses. Sword bayonets were created to produce a bayonet that also served as an infantryman’s hanger. The yataghan configuration blade provided better clearance for the hand when reloading a muzzle-loading weapon. The blade shape is not without other merits so a number of breech loaders also used sabre bayonets.