Today I am going to try and bring together some of my ideas regarding survival kit and selection of contents. When possible, I try to approach topics from a different perspective to that echoed on most websites.

Regular readers may know that I have my reservations about the “little tin of gizmos”. Thinking that you are covered because you have a couple of band-aids and a couple of loose fishing hooks and swivels is a recipe for disaster.

Survival kit may exist on several levels. On your person you will have your skin-level EDC. Most of mine is in the pockets of my trousers, although some items are on my trouser belt or key-ring. If you are carrying a bag, it is prudent to have some additional items in your bag. You consume the items in your bag in preference to your skin-level items. Military personnel often have an intermediate level in their webbing load-bearing equipment. Ideally this should only hold ammo, weapons, some water and immediate first aid items but the tendency to add additional gear is common. A larger pack or vehicle may provide higher levels of survival gear. One should always plan for the contingency that one may get separated from bags or vehicles. This is why your skin-level gear is important.

My current planning list looks like this:

Seven Tools of EDC

Hat, Towel, Rope

Medical, Writing, Fire, Knife

Foundation Survival Kit

Blanket, Fire, Knife

Poncho, Water, Toilet Paper, Canteen Cup

Travelling Kit

Navigation, Signalling, Illumination

Washing, Repairs, Food,

Documentation, Money, Clothing, Armament

The item names are memory aids and should be taken generically rather than specifically. “Knife” represents other tools, “blanket” represents sleeping bags and related items and so on.

The Seven Tools of EDC

The Seven Tools of EDC were inspired by the roguku or Six Tools of Travelling. I remember these as three flexible things (hat, towel and rope), three multi-part things (medical kit, fire kit and writing kit) and a knife.

“Hat” represents other protective clothing, such as gloves, goggles and sun-glasses. At “skin-level” this will be whatever headgear and other items suits the current or expected weather. If I am taking a bag I will probably have two hats. One will be to protect from the sun and keep the rain off my glasses, probably a boonie hat. The other will be a warm hat such as a watch cap or headover. If it is really cold spare gloves and headover are a prudent precaution.

“Towel” in this context is a multi-purpose piece of cloth. At skin-level this is a bandanna in my pocket but recently I have also been wearing a shemagh. If I lose or did not bring my hat these can serve as head coverings. Any bag I carry usually has a spare bandanna and/or shemagh in it. In colder conditions the shemagh is replaced or supplemented by a woollen or acrylic scarf.

“Rope” for the ninja may have meant a grappling hook and rope. For me this reminds me to carry some cordage. At skin-level this is a couple of armspans of paracord, a hank of string, a container of dental floss and a retaining cord for my glasses. Packs contain longer lengths of paracord. If heading for the deep wilderness I would have a toggle rope or the modern equivalent.

Medical Kit. On my person I have a small number of plasters, alcohol wipes and pain-killers, plus some personal medication. I have a more extensive medical kit I carry in daysacs, plus a bigger kit in my travelling bags. Medical also includes such items as insect repellent and sun cream. These are usually bag items but certain conditions may require a small supply to be carried on your person. Whenever possible items are consumed from the larger kits before the skin-level kit.

Writing represents communication and recording. In my pockets I carry a pen, pencil and two pieces of chalk (one light, one dark colour). Usually have a phone on my belt. Daysac may contain a notepad in a plastic bag. When on holiday I keep a journal.

Fire Kit. For everyday use this is simply a disposable lighter riding in the bottom of a pocket. I carry a plastic bag with a couple of tissues in, which could be used as tinder. If straying further afield I would add a container of tinder, fresnel lens and spare lighter to my pockets. Daysac has a couple of spare lighters and some candles.

“Knife” represents tools and related hardware. My Swiss Army Knife goes nearly everywhere with me. I also have a Leatherman Squirt and pocket prybar on my person. A diamond impregnated metal card is carried for sharpening.

Foundation Survival Kit

The items on the Foundation Survival List are mainly bulkier “bag” items, with a couple of significant exceptions.

“Blanket” represents sleeping items in general. It includes poncho-liners, sleeping bags, cloaks and long coats. These can keep you warm, even when not sleeping. This category is called “blanket” to remind us about the survival blanket, which is compact enough you can easily fit one or more in a trouser cargo pocket. They are reasonably priced so you can buy a dozen and stick spares in coat pockets and any bags you might carry. As well as keeping you warm, they can keep the rain off, spread out as a signalling panel, possibly even used as a heliograph. One is in the little medical pouch that carries most of my skin-level EDC. For decades now my daysac has carried the survival blanket’s larger cousin, an All-Weather Blanket.

Fire Kit. A fire kit was included in the original Foundation Kit list. It is repeated since the ability to create a fire is an important component of survival. Have a means of making fire on your person, and additional means in your bag. Consume the bag supplies before that on your person.

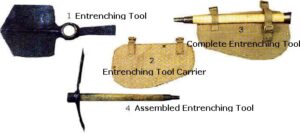

Knife. Another duplication, but repeated for much the same reason. In this context it can be read as “a bigger knife”. Useful as a pocket knife or muli-tool are, they can only get you so far. This category also reminds us to remember other, larger tools such as a crowbar or entrenching tool. Have a fixed-blade knife on your trouser belt. If you lose your pack, webbing or even your jacket or shirt you will still have a useful survival tool.

Poncho includes other forms of rain-proof clothing and shelter items such as tarps, tents, shelter halves, basha-sheets, groundsheets and so on. Any bag of sufficient size should include a means of rain protection.

Water represents a means to carry water, and the means to ensure that it is drinkable, such as water purification tablets. In rural areas a supply of water and purification tablets should be both on your person and in your pack. Consume the water in your pack before that on your person.

Toilet Paper. A roll of toilet paper in a waterproof bag is a prudent addition to any bag. A small bag with a couple of paper tissues rides in a cargo pocket of my trousers. A bag with additional tissues will be added if I am heading off the beaten track. As well as intended use, such tissues can be used for nosebleeds, nose-blowing and as tinder.

Canteen Cup. A metal canteen cup or similar small cooking vessel is a useful addition to the above items. Boiling water to sterilize it will conserve water-purification tablets. It can also be used to sterilize instruments or blades intended for medical uses. Even if you wear a water bottle on your person, the canteen cup is probably best carried as a pack it. The interior can be packed with some of the smaller items listed above.

There is a survival adage that says you cannot live three minutes without oxygen, three hours without shelter can kill you, you can last three days without water and three weeks without food. The Foundation Kit contains the essentials towards keeping you alive beyond three days.

Travelling Kit

What I have chosen to call the “Travelling Kit” are mainly “very useful” rather than essential. Food is obviously essential, but you can last several days or more without it.

Repairs. If away from home, a small repair kit is worth putting together. My compact little sewing kit has seen many uses over the years. This is supplemented by a couple of rucksac buckles, dental floss, a roll of electrical tape and a tube of superglue. A small screwdriver that fits in my Swiss Army Knife corkscrew has been used to repair several pairs of glasses. I have seen it suggested that a piece of glue stick of the type intended for hot glue guns may also be useful. You can even add a little repair capability to your skin-level kit. A small bag of safety pins can deal with tears and zipper problems. Around the pencil I have wrapped a length of electrical tape then bound two threaded needles to its sides.

Food includes food procurement and cooking means. Put together a small fishing kit, with some wire traces that can be used as snares in extremis. Assemble as much of the kit as is practical before hand. Sitting in the wind and rain as the light fades is no time to be tying on swivels! Add the fishing kit to your trouser pocket items if heading into the wilds. The food you carry should include some items that can be consumed without heating or rehydrating. Some boiled sweets/ hard candy is a useful addition to any daysac, giving a quick energy boost when it is needed.

Illumination. There are numerous small flashlights that are suitable for skin-level EDC. The little Photon lights can be added to a keyring, dogtag chain or whistle lanyard. A larger flashlight is a suitable addition to a daysac or larger pack. My daysac has a handcrank model in it.

Navigation. Personally, I have found a small compass a useful addition to my EDC. Even in town it is sometimes useful to know which direction is which. A number of guidebooks have information such as “…the hostel is to the northwest of the piazza”. If travelling away from civilization better maps and compass are recommended. GPS is nice, but you should plan for when it stops working. Without a compass there are other ways to determine direction, which is why these items are under “very useful” rather than essential. Worth repeating is that in most cases where rescue can reasonably be expected your chances of survival are better if you stay put rather than walking out.

Signalling. Signalling assumes there is somewhere out there to signal to. Flares are not much use if no one is likely to be in line of sight. Tell someone where you are going and when you will be overdue. Signalling overlaps with Illumination and Fire, and mobile phones have already been mentioned. Your skin-level kit should include a whistle. Mine is on my key-ring. A small heliograph is easily fabricated. The back of my phone is mirror-polished, so I would use this instead.

Washing. If you do any travelling you should put together a lightweight wash kit. How to put one together is detailed on another page. I prefer mesh bags over the more elaborate, heavier and more expensive wash bags.

Documentation. Travelling may require visa, permits, passports and other documentation. Make sure you have it all before any trip, and store in a waterproof bag. Make photocopies of important documents, such as your passport, and carry then separately to the originals. I prefer to carry some of these things on my person rather than in a bag.

Money. In some environments, one of your most useful tools. Includes credit, debit and ATM cards. Have information on what to do if you lose the latter. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket!

Clothing. How much spare clothing, its type and quantity will depend on trip duration and conditions.

Armament. Carry if you can. The world is full of nasty people who will rob you or hurt you just because they can.