Decades ago I wrote a piece called something like “Travelling the World with a 30 Litre Pack”. This was so long ago it was on a floppy disc and it only ever got read as a print-out. That article is long since lost, but the experiences that contributed to it has also fueled many of the articles on this blog. I was asked if I could attempt to reproduce the article, since much of it is still relevant to travelers today.

Firstly, I will point out this was not intended for wilderness expeditions or camping trips, but for holidays in areas where youth hostels or similar accommodation was available. On the trips where I expected to also do some camping, I carried a larger pack and more gear. Thinking back, I never personally made any of my trips with just a 30 litre pack. My daysac was smaller, and I already owned several larger packs. Money was often tight so I never got around to buying myself a nice 30. That said, one of the people who read the original article was inspired to spent nearly a month traveling around India with just a small pack.

One advantage of a larger pack is that you can carry a packed daysac inside it, which saves a lot of unpacking and packing when you want to dump the gear you don’t need for a few hours of sightseeing.

One of the products of my travels was “Uncle Phil’s List”, so I will use its categories for the following description.

The first category was “shelter”, which divides into shelter, sleeping and clothing.

Accommodation was in hostels or budget accommodation. The former were preferred for their social aspect, and I have many fine memories from such stays. The only thing I needed to carry for shelter was a credit card and a YHA membership card.

My daysac carried (and still has) an all-weather blanket, which over the years has been put to many uses.

Many youth hostels do insist you have a sleeping bag liner. Mine got accidentally placed in the laundry on my last day at a hostel. My current one was sewn from the sheets the apologetic warden offered me as replacement. The top of the bag has some very distinctive cloth added to the top, to avoid this happening again. If I have to unpack in the dark the texture helps me orientate the bag. There are silk liners, which look really nice, but again, I have never been able to justify the expense.

I also carried a Merlin Softie one-season sleeping bag. This packs to the size of a rugby ball without using compression straps. Very useful when the bedding provided was not up to standard, or when I had to sleep on a bus, train or ferry on an overnight journey. Overnight trips were a useful trick when traveling on a tight budget. Saved on a night’s accommodation and got you to a new place to see.

Careful selection of clothing can save you lots of weight. I encountered travelers who were carrying 20+ kg of clothes!

The trick is to select items that were easy to hand-wash, and just as importantly, quick to dry. I was fortunate that about the time I began traveling there were lots of reasonably priced silk shirts on sale. My basic travel wardrobe was two long-sleeved silk shirts and two short-sleeved. Theoretically, if it was cold I could have wore a short-sleeve under a long, but don’t ever recall this need arising. Denmark was a little chilly, so I brought a thin woolen jumper to supplement my usual gear. I did not know about “ranger rolling” back then. I could probably have packed things even smaller.

Underwear was three pairs of black swimming shorts, the sort with pockets and inner liners. If the day was hot I could easily remove my trousers and be already in shorts. Due to the odd climate inside airliners, for the flight out I found cotton underpants more comfortable. These would probably not be worn again until the flight back. I might wear a cotton tee-shirt for the flights instead of the silks. More commonly, I wore a casual cotton shirt that served as a light jacket for the rest of the trip.

The markets no longer seem to have reasonably priced silk shirts so as mine have worn out I have replaced them with the newer microfibre synthetics.

Just before a trip I would treat myself to some new socks, usually white cotton sports socks. Three pairs of these would go in the bag and a fourth pair worn on the trip out. When I began to get pains in my legs when flying I added a pair of compression socks to my load-out.

I carried two pairs of trousers, basically a “wear and a spare”. Cargoes’ would be fine, although one of my pairs was “smarter”. On some trips I hooked up with friends I had made on other trips. This often involved a family dinner so being able to smarten-up was useful. At the airport I often needed my passport and boarding pass readily to hand, and the large thigh pockets of the cargo trousers was very useful for this.

Since I was carrying a pack, and sometimes had to deal with rough terrain, including cobbled streets within towns, ankle support was a priority. Most of my trips were to hotter climes, so footwear of choice was canvas hiking boots. Honourable mention goes to my Hi-Tech Sierras. I only wore these during holidays, but they did so many miles the soles were treadless by the time I had to retire them. I was most disappointed to discover the line had been discontinued. The Hi-Tech Trilogies I brought as replacement nearly crippled me. My tendons bled and my toes too, if I recall correctly. Brand new white cotton socks soaked in blood. I have a different set of canvas boots now. Unlike the Sierras these have gore-tex. You don’t need gore-tex for what I am using them for, but finding canvas boots without it no longer seemed to be possible. In addition to the boots I also carried a pair of espadrilles or kung-fu slippers. If you have been wearing boots all day it is nice to slip into these when you head into town looking for dinner and a beer.

An important item was a rainproof jacket, ideally a lightweight one that packed into its own pocket or small pouch. The latter quality was far more important than it being breathable or some wonder fabric. I discovered that breathable waterproofs have a finite life, and you get to know that time is up the hard way, during a rainstorm!

I carried a lightweight jacket of some synthetic material for some protection against the wind. One of these had a cotton liner which I replaced with one made from a silk shirt. I don’t recall using these jackets much. Often I would use my cotton shirt, fleece or rainproof. I carried a fleece for colder days and evenings. This had a more windproof outer than most fleeces, so was more practical for outerwear.

Clothing included a boonie hat for sun protection, and several bandannas, one in a trouser pocket, the others in the pack. I carried a pair of gloves, although seldom needed them in hot climates.

The secret to carrying so little clothing is being willing to clean it during your trip. You will notice that most of the items I carried are quick-drying materials such as synthetics or silk. The cotton socks are an obvious exception, but these dried pretty well in the climates I traveled in. In such conditions putting on slightly damp socks was not a health problem.

The only laundry gear I carried was a small nail brush. The same soap I washed and shaved myself with served as detergent. Washing socks generally involved putting them over my hands and “washing my hands”. The brush worked well on collars. Often I would step into a shower wearing a silk shirt and clutching a bundle of other items to wash. Hang a silk shirt on a hanger and it dries without needing ironing. In fact, the same is true of cotton tee-shirts!

Moving on to other categories: I carry a lighter as part of my EDC, which covered the requirement for fire. My daysac carried a water-bottle, although this might be moved to the outer pocket of a larger pack if I was carrying one. On more recent trips this has been one of my Platypus bottles, often the larger one with a drinking tube. On some trips I simply brought a large bottle of soda in a local store, then used the bottle for water once the soda was drunk. For most of my trips you could trust the local tap-water, but I did acquire a cup device that chlorinated water passed through it. You might wise to include a bottle of purification tablets instead.

I was seldom anywhere where I could not purchase food. The times I was, a few hours hungry would not kill me. Thus I carried nothing to cook with on hosteling trips. The bag soon acquired some local foods such as fruit, salami, bread and cheese. I can still recall sitting outside the Parthenon, making a sandwich with my penknife and surrounded by feral cats sunning themselves. I learnt to carry a bag of boiled sweets (aka “hard candy”). These provided an energy boost when climbing hills: most sights to see seem to be up hills or high up! And I will admit that offering a sweet to a fellow traveler was a great ice-breaker and gained me some very memorable companions over the years.

My travel medical kit I have described elsewhere. Medication appears in my current load-out, but I did not need such things in my younger days! My daysac included a bottle of sunscreen and one of insect repellent. These days you will have to ensure that the volumes of these are less than 100mls if you intend to travel by air. Another item for your daysac is a roll of toilet paper in a plastic bag. Over the years I refined and optimized my wash kit. This is described here.

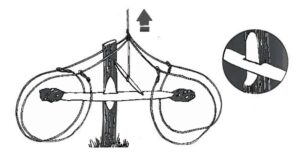

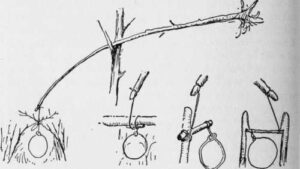

My tiny sewing kit has seen a lot of use over the years, so is something it would be very foolish not to carry. My “spares and repairs” includes a couple of spare rucksac buckles, electrical tape, string and a tube of superglue.

Documents included my passport and any visa needed. Plane tickets: no e-tickets on smart phones back then! In Europe I carried the E111 medical treatment form, but these may no longer be valid. A zipped pouch such as a pencil case proved very useful to hold documents and other miscellaneous items. Traveler cheques, although I doubt modern travelers carry these. A photocopy of my passport, and record of the traveler cheque numbers went in the pencil case. I did have my cheques stolen on one trip, and got all my money back, since I had the numbers to cancel them. Wisely, I carried my credit card in a different place so that was not stolen. A couple of guide books, usually borrowed from the local library at home. Have more than one, since entries can be misleading or inaccurate. A phrasebook. A novel or similar to read while waiting for trains or just sitting in the sun. A notepad in a plastic bag, and something to write with.

I carried my penknife on my person, and often it has proved useful. My daysac included a flashlight of some form, in an outside pocket so it was readily accessible. A telescopic hiking pole was a blessing on steep terrain or when tired.

One of the first things I would do when reaching a new town was locate the tourist office and acquire any street maps they had. My EDC includes a Suunto Clipper compass and this has often proved useful when navigating a strange town.

An item conspicuously absent from my original article was a mobile phone. They were only just coming in, they needed frequent recharging, and you were unlikely to find facilities to charge them, back then. My trips were an escape, so I made a point of leaving all my electronic devices at home, which probably would have been a Walkman back then! Not really being a photographer, I also never bothered carrying a camera.

Few backpacks are totally waterproof, so the contents should be in one or more plastic bags. These needn’t be anything expensive, just intact. If you are traveling with just one pack I suggest you divide the contents with at least two bags. One bag holds your bedding, wash-kit and most of your clothing. The other bag has the items you may need during a day’s sightseeing: medical kit, guide books, raincoat etc.