Recently, my computer began to lag, so I ran a chkdsk on it. This took some time, so I decided to read in the more traditional manner.

My choice was a printed copy of Richard F. Burton’s “The Book of the Sword” (1884). I have dipped into this book on occasions, but never actually read it from cover to cover.

Throwing Stones

In the introduction and preamble, Burton discusses humanity’s need for weapons, their disposition to violence and the forms and possible inspirations of early armaments.

I was particularly struck (pun intended!) by the discussion of hand‑throwing of stones.

Humans, however, are able to throw with sufficient accuracy to deliberately hit and injure an intended target. Indeed, there are indications that aptitude in this ability may have been an evolutionarily selected trait and have contributed to human sexual dimorphism.

In the Iliad, duelling heroes pick up great rocks and hurl them at each other.

Classical armies are believed to have included units of stone throwing warriors, known as “petrobóloi” or “lithobóloi”. Since these terms mean “stone-thrower”, some of these references may alternately refer to men armed with slings or catapult‑type war engines.

A little later in history, the Roman Vegetius states: “[Legionary] Recruits are to be taught the art of throwing stones both with the hand and sling.” and “Formerly all soldiers were trained to the practice of throwing stones of a pound weight with the hand, as this was thought a readier method since it did not require a sling.”

It is worth bearing in mind that accurate use of a sling is very difficult and requires considerable time and training. Having legionaries lob stones at enemies was much more practical.

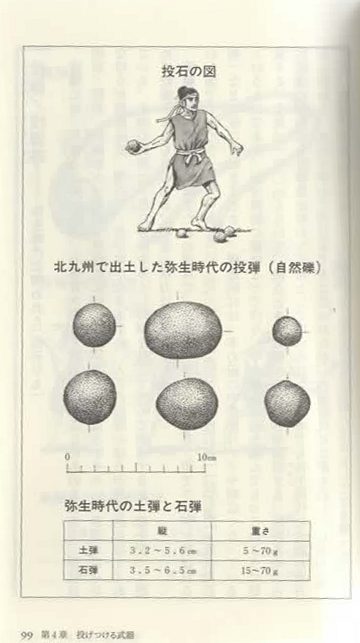

Japanese armies also had low-ranking warriors whose speciality was throwing stones (ishinage/ishiuchi/inji/sekisen/tōseki/isi arasoi/isi gassen), the stones known as tsubute. (“Classic Weaponry of Japan”, p.156, Serge Mol)

Burton gives several examples of stones used in hunting or war (p.16): “Diodorus of Sicily (B.C. 44)…says that the Libyans [possibly a generic term for North Africans] ‘use neither Swords, spears, nor other weapons; but only three darts [javelins] and stones in certain leather budgets [bags/sacks], wherewith they fight in pursuing and retreating.’”

He also describes how raiding “Arab Bedawin”, rather than use their matchlocks, will pelt an enemy with rocks, causing him to uselessly expend his ammunition.

Burton also remarks: “As a rule, the shepherd is everywhere a skilful stone-thrower.”

In “The Art of Attack” (1906), p.153, Henry Swainson Cowper notes: “Stone throwing as a method of attack would come natural to our earliest forefathers, like the use of the simplest club. Indeed such use might precede the last named, since no branch could be used without some trimming, while suitable stones lay ready almost everywhere.” and on p.159, footnote 2, “It seems natural for man, when irritable to " chuck " the nearest available object, whether a stone or a decanter, at the offender, whether that be a dog or a relative.”

As well as being a weapon system for hunting and war, stone‑throwing has been used for a number of other purposes.

Stones may be used to bring down fruit and nuts from trees. It is probable that thrown stones have been used to drive predators and scavengers away from a kill, and birds and other animals away from the crops and herds. Thrown stones have been used for duelling, as a means of execution, and as an exhibition of disapproval, discouragement, harassment and religious devotion. I even encountered suggestions that throwing stones could be used for stress relief (other than the obvious option of throwing them at whoever bothers you!).

One might also reflect at the various sports and fun‑fair or carnival games that involve throwing balls or other stone‑like objects.

Stones deemed most effective as missiles were those of 0.5 to 0.75 kg (figure 6). The stones used naturally weathered into spheroids, and diameter of suitable missiles was approximately that of a tennis ball, which would be around 67 mm, incidentally very close to that of an M67 grenade (64 mm).

Another interesting feature of this study was that the simulated target was a 57 kg antelope at 25 metres.

In a genuine survival situation, a thrown stone may be useful for more than just squirrels, rabbits and birds!

Not all stones are created equal, and good throwing stones may not be as readily available in some environments as you may wish.

Cowper (p.150) notes that the natives of Tierra del Fuego carry a little store of stones for throwing in the corner of their mantles. Many other stone throwing peoples also carried stones on their person.

Undoubtedly, stones were often selected for suitable mass, and for regularity and consistency of shape. Shaping and polishing stones to create better missiles is not unknown.

“Ancient Chinese Hidden Weapons” by Douglas H. Y. Hsieh suggests carrying a bag a foot deep and seven inches across to hold suitable “locust” (sharp) stones encountered, or two bags each holding six pebbles. Readers can probably think of other practical uses for a bag of stones.

Hsieh's book also suggests “Anyone who intends to jump down from a height in poor visibility must use a stone to see if the ground is safe”.

Despite this long and broad history, the potential of hand‑thrown stones is often overlooked by survivalists.

In modern times, we associate stone‑throwing with rioters and hoodlums.

Survival manuals that describe field expedient weapons generally ignore the use of stones, other than as ammunition for slings and hand‑catapults/slingshots.

Rubber and elastic perish and break.

While a sling is easily constructed and has formidable power and range, learning to use it accurately enough to hunt with will probably involve weeks and months of practice.

As an aside, if you do have the cordage to make a sling, you may be better off making a bolas! The bolas is a clubbing weapon as well as an entangling one, so is related to the thrown stone.

Bolas are best used in open terrain. Bushes and trees give them problems.

Cords of more than a metre may be used for bolas, and heavier weights than those suggested in FM 3‑05.70 used. Blackmore (p.327) gives a range of 1 to 1.5 lbs for each weight.

Many people interested in survival or martial arts devote considerable time and money acquiring and learning how to throw knives, axes, shuriken, coins, darts or spikes. Stones are far more likely to be available in a defensive or hunting situation.

In his book Shuriken-Do, Shirakami suggest women carry several golf balls in their bags. Hold one in each hand and throw the pair in quick succession.

If you are serious about keeping yourself fed or defended, putting in some practice at throwing stones by hand would be prudent.

A practice range for stone throwing is easily constructed, even when out in the wilds. A tree, post, mound or object hanging from a tree may be used as a target.

Start learning at a range of about three metres. Increase distance and reduce target size as you improve. Cups or buckets on their sides make good targets,

“Shuriken An Illustrated Guide” by Fujita Seiko in the section on stone throwing (Tsubute Jutsu, also known as Ishi Hajiki Jutsu) gives the useful advice: “You should always aim to hit above your actual target while your hand should drop down below your target as you throw. For example, if you want to strike an enemy in the face, your hand should drop down to his chin as you throw…To throw properly you need to understand how to aim, stand with your foot facing your target and throw as if you are trying to impale it”.

In the illustrations a right handed throw is shown with the left foot forward and the left hand pointed toward the target. Hold some “reloads” in your free hand.

Throwing Sticks

Throwing stones may be supplemented by throwing sticks.

Compared to a thrown stone, a throwing stick has a greater chance of hitting a target, and a greater range.

In their very simplest, a throwing stick is a piece of wood picked up off the ground or broken from a tree and thrown at a target. Such simple throwing sticks are useful for knocking fruit out of trees, or casting a bear‑line over a tree branch.

This video shows a very simple baton-style throwing stick made from a length of hardwood timber, as long as the arm and as thick as the wrist. Ideally this should be as free of knots and other non‑aerodynamic projections as possible.

Sharpening each end will increase its utility both as a weapon and as a digging tool. The other end may be cut into a wedge shape to aid in removal of loose soil.

More effective throwing sticks will take a little more fabrication.

Throwing sticks may be dived into those that have an aerodynamic cross‑section, and those that do not.

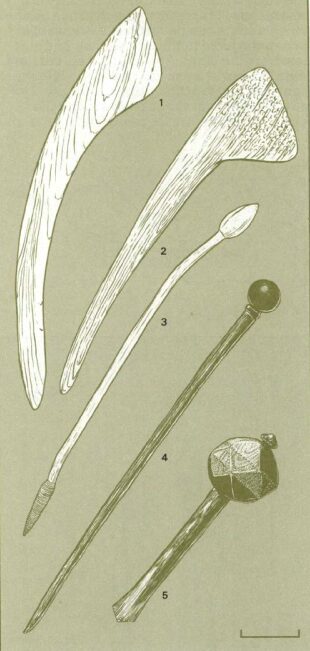

The latter type (above) are often weighted towards one end, and may resemble a knobkerry or shillelagh.

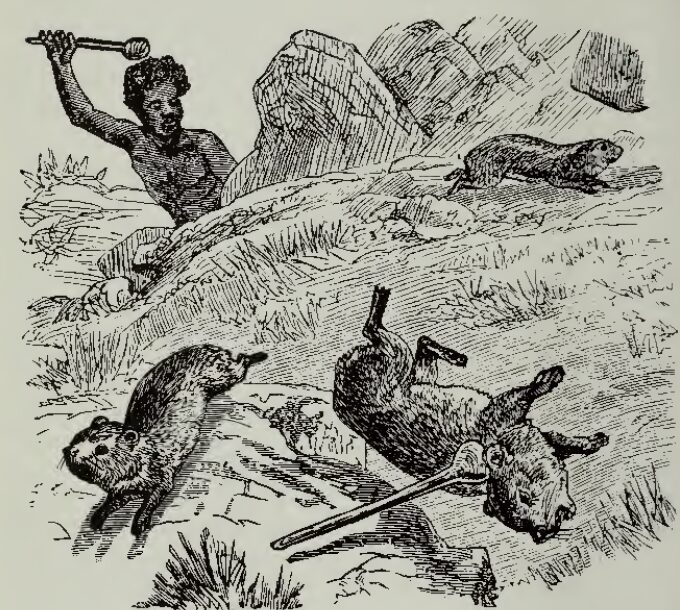

The next illustration is taken from “Hunting Weapons” by Howard L. Blackmore, and shows hyrax being hunted.

Two hunters would work together, about 50 yards apart. Both would throw at the same time so that an animal dodging one club would be hit by the other. When hunting birds, one hunter cast his club above the bird, the other below.

A knobkerry or shillelagh‑type club may be made from where a branch or root grows from a larger part.

The next illustration shows an alternated configuration of throwing club, cut from the junction of where a minor branch joins a major one.

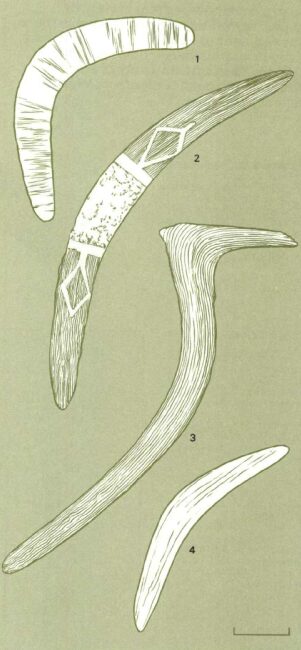

When it comes to aerodynamic throwing sticks, some mention must be made of the “boomerang”.

In modern usage, the term “boomerang” is generally used for returning throwing sticks. To return, a boomerang needs to be launched in a specific direction, relative to the wind. It also needs to be relatively light, making it impractical as a hunting weapon except against lightly-framed fowl.

Non-returning boomerangs intended for hunting and warfare may be up to a metre long, and may have a range of 150 yards (Cowper, p.166).

The term “boomerang” was originally a name only used in part of Australia, and according to many authors, was originally used for non-returning hunting and fighting weapons!

Burton notes (p.33): “The form of throwing-stick, which we have taught ourselves to call by an Australian name ‘boomerang,’ thereby unduly localising an almost universal weapon from Eskimo-land to Australia, was evidently a precursor of the wooden Sword. It was well known to the ancient Egyptians.”

Survival field manuals such as FM 3‑05.70 tell you to make a “rabbit stick” from “a stout stick as long as your arm, from fingertip to shoulder” (p.8‑26) and from “a blunt stick, naturally curved at about a 45-degree angle” (p.12‑8)

Some sources will tell you that a hunting throwing stick should be widest at the centre and thinner and tapered towards the tips. This is an effective form, but even if we restrict ourselves to looking at Australian designs, other forms may be encountered.

The illustration below shows a “beaked” war‑boomerang (3).

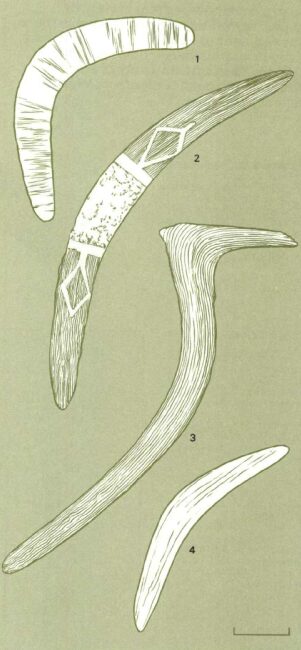

The image below shows an Australian weapon known as a “lil‑lil” besides a more familiar style of throwing stick.

The lil-lil is classed as a club rather than a boomerang, but is also used as a throwing weapon. This design has inspired some weapons that do have an aerodynamic cross-section.

Both the beaked boomerang and lil-lil clearly concentrate mass towards one end rather than the centre.

Cowper shows a wide variety of curved throwing sticks, ranging from gentle S‑forms to sabre, hook and horn shapes.

In other words, you have considerable leeway in the shape of your throwing stick.

FM 3‑05.70 also tells the survivor to “Shave off two opposite sides so that the stick is flat like a boomerang.” which I think is a little misleading.

Aerodynamic throwing sticks often have a cross‑section that is described as “semi‑lenticular”. In other words, the lower surface flat‑ish and the upper convex. The edge formed concentrates the force of impact, hence Burton’s reference to wooden swords or edged clubs.

Cowper notes that some war‑boomerangs have one side flatter, which suggests this may not be as pronounced as seen on “comebacks”. He also mentions an Indian war-boomerang with both sides rounded. There is therefore some leeway in the cross‑section you give your throwing stick, depending on the tools and the time you have.

A practical bow and arrow, or even a good spear take considerable skill to produce in a survival scenario.

Manufacture of a throwing stick is easier and more forgiving. Your chances of bagging a meal with it are also much greater.

Like any other weapon system, you will still need to put in the time practicing!

There are plenty of websites and videos describing how to make and use throwing sticks, so I will not go into further detail here.

Depending on how it was constructed, a throwing stick may serve other purposes too.

Many types are suitable for use as digging sticks. Some knobkerry or shillelagh are long enough to serve as walking sticks, which is handy when traversing rough terrain. Throwing sticks may also serve as hand weapons, useful in dispatching caught fish or trapped animals.

It is a good idea to construct a pair of throwing sticks, providing you with the means to make a follow‑up attack, or defend yourself.