Rummaging through a on-line drive the other day and I came across a filename that was just a string of numbers and letters.

This turned out to be a copy of Air Force Survival Manual AFM 64-5. I had not originally paid much attention to this particular work when I downloaded it along with some other military survival manuals.

Unlike most works of its ilk, AFM 64-5 is concise and very readable. It also contains a number of items of information that do not usually appear in many of the survival manuals that will be more familiar to the reader.

One of the many things that interested me was the manual emphasised that a survivor only needed about three ounces of protein a day.

A surprisingly sound and up-to-date piece of nutritional advice in a book that dates back to the 1950s.

It also flies in the face of the current food-fad of boosting the protein content of everything!

For those of you who did not pay attention in school, your daily protein needs are relatively modest.

Even if you are a body-builder, you are not likely to grow more than a few grams of muscle a day.

Having a little extra protein is not likely to harm you. Most of it just gets peed out.

Foods rich in protein have been noted to increase satiation, which is why items such a nuts are sometimes recommended for snacking.

Excessive quantities of protein consumption may have medical effects, however.

Most protein sources also include fats, oils, salt and other things we generally consume too much of already.

I have become more interested in portion control since I was declared diabetic. Like so many of us, I could do with losing a few kilos. This may help me keep the diabetes under control.

Also, on a planet where much of the population is either going hungry or obese, it seems morally abhorrent to deliberately be eating much larger quantities of food than I need.

Portion control has obvious applications for survival, hiking or prepping. It allows you to more accurately judge how much food per day you will need for a journey or a stockpile.

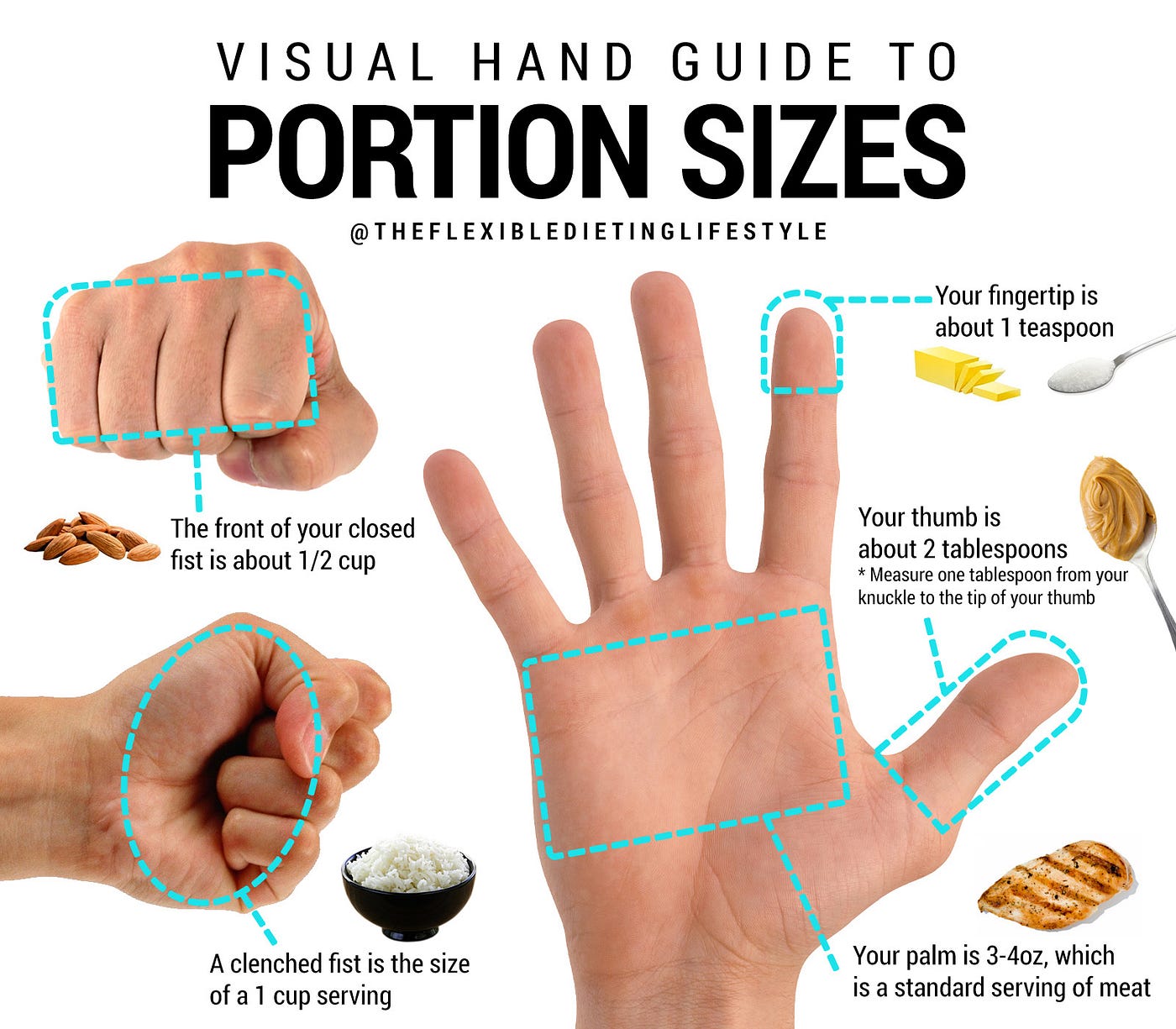

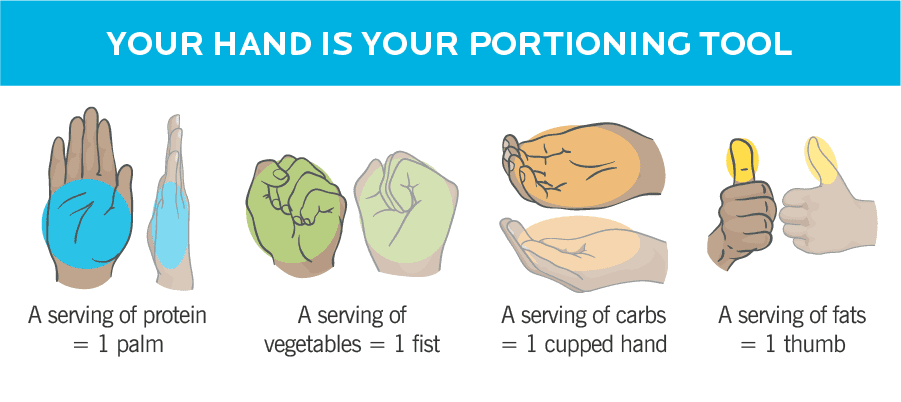

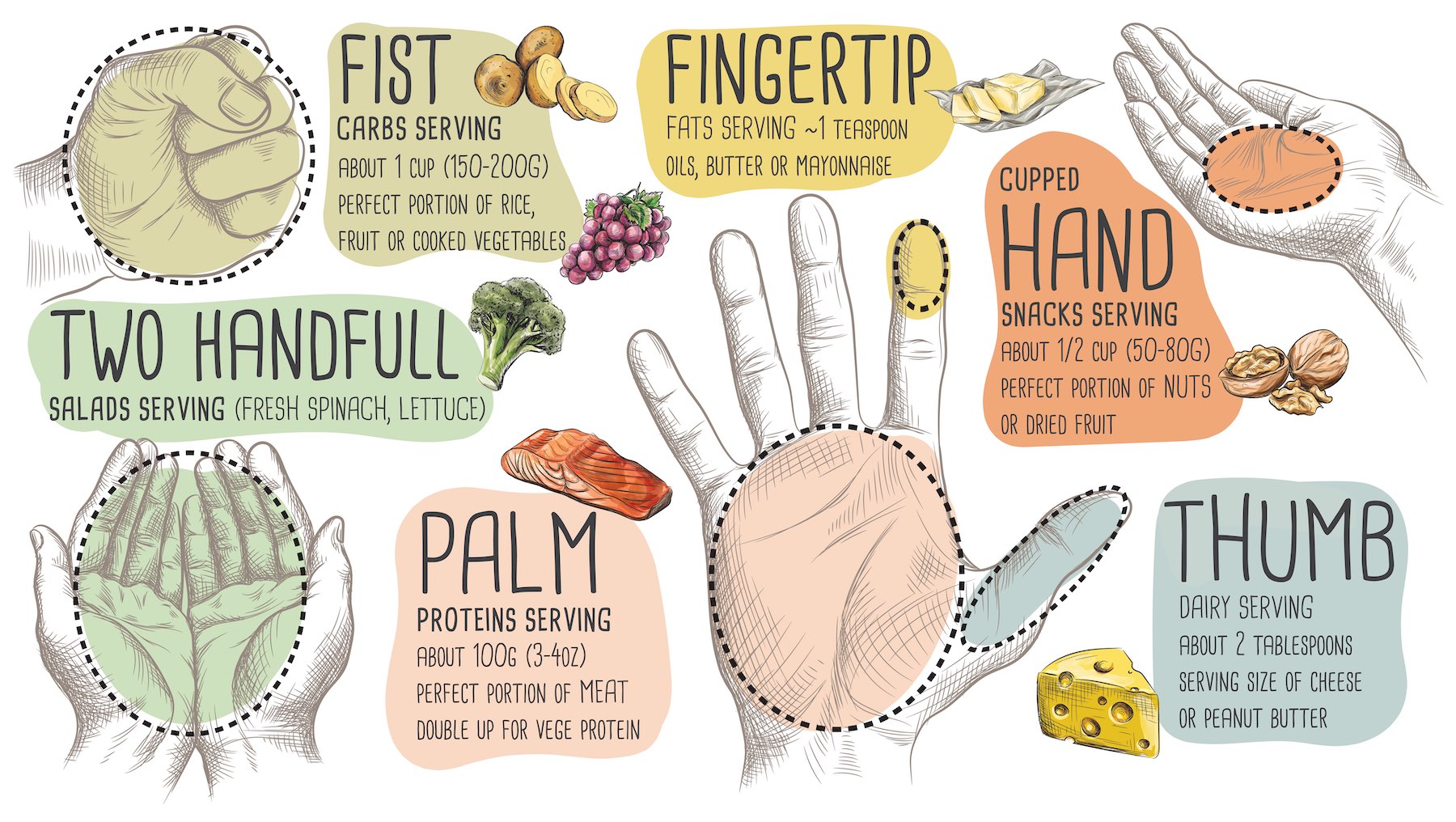

Reading about daily recommendations for protein introduced me to the concept of estimating portions relative to the hands. You will find many websites and illustrations of these. Some differ on the fine details and recommended quantities. My personal take-away may be summarised thus:

Protein

A portion of meat should be about the size of the palm of your hand. This is about the size of a burger, one or two sausages, a small chop or chicken quarter.

Lean meat, and meat cooked by methods that minimise fat content are obviously preferable.

Fish is a little more complicated.

Oily fish has oils and fats, so is treated the same as meat, with a portion about palm-sized.

You may have a larger portion of white fish. A piece should be about the size of your open hand (i.e. palm and fingers, a hand-length). If you like your fish battered or breaded, I recommend baking it in a halogen oven rather than frying it. Quick, easy and delicious!

An old book I have suggests that meat should be used like a condiment, and only consumed in quantity one a week.

I feel that remains sound advice.

Carbohydrates

The carbs that you are most likely to be eating are mainly derived from cereals and grains. This class also includes beans, potatoes, and some vegetables such as sweetcorn. These are all rich in starches, which digest down into sugars. Sugar is also a carbohydrate, but we will deal with that separately later.

The carbs component of your meal should not exceed a cupful.

A clenched fish is equivalent to about a cupful (236-250 ml). The “face” of a fist is about half a cupful.

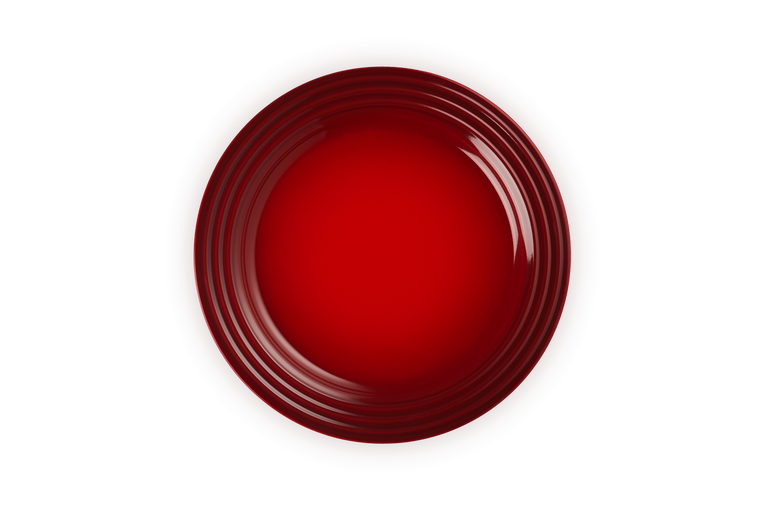

An alternate/additional approach to estimating a portion is that your carbohydrates should occupy about a quarter of the plate.

Some carbs, such as brown rice or wholemeal bread or pasta are a little richer in fibre or nutrients, but there is more merit in having a variety of types.

Fruit and Vegetables

Or more specifically, plant foods that do not count as being high in starch.

Some fruits are high in sugars, which some readers may need to bear in mind.

Generally, the recommended portion size for the non-starchy veg is two handfuls, or about half the plate. And unlike the above, this is a minimum recommended portion.

If you want to add more low-calorie foods such as vegetables, pile them on.

Have a good variety of vegetables to prevent eating them becoming monotonous.

Fingers and Thumbs

Other meal components such as sugar, salt, oil/salad dressing should be used in moderation.

A fingertip is about the equivalent to a teaspoon (5 ml). A thumb is about two tablespoons (30 ml), so half a thumb one tablespoon/15 ml.

As an aside, I was bemused to see my local pharmacist offering a bag of glucose/dextrose (with a hefty markup!) as “an alternative to sugar”.

Back to school again! Glucose/dextrose is a monosaccharide of glucose. Sucrose is a disaccharide of glucose and fructose. All are digested by the same route and have the same food value. You will see marvellous claims made about honey, but foodwise it is mainly glucose and fructose.

I like a sprinkle of sugar or drizzle of honey on my porridge, but make sure it is only a teaspoon.

Americans tend to write recipes in volumes (cups and spoons), while Brits are more likely to use masses.

If you are a Brit and considering paying more attention to your portion sizing, I recommend investing in a set of measuring cups and spoons.

Very soon you will understand equivalents like that a 40 gram portion of oats is about half a measuring cup, and how much this is compared to your fist.

One of the beauties of the hand measuring system is you always have it “handy”.

Spice is the Variety of Life

It is a good idea to have an assortment of sauces, spices and salad dressings to add extra variety to your meals from day to day.

This recommendation applies to both your home kitchen and your backpack. When you are out in the sticks and may need to eat the same food several days running, a dash of sauce or sprinkle of curry powder or chilli can make a lot of difference.

Snacking

One definition of a snack is eating for entertainment or a non-essential meal. I therefore try to limit my snacking.

Sometimes, however, you do need something quick to tide you over until dinner, or ward off a imminent migraine attack.

The recommended portion for a snack is a handful (about a quarter to third of a cup, or 30-55 mls may be a better measure). This may be a piece of fruit such as an apple or orange, or a handful of nuts, sultanas, cherries or similar.

Protein containing snacks may satiate you better. At other times you may need the carbs and sugars.

A handful of fruit makes a nice dessert to end a meal.

The important point is to stick to the handful portion size. This takes a bit of self-discipline, but you are unlikely to lose weight without this. Self-discipline is a personal property that grows with exercise and practice.

If you are prone to snacking, I suggest you stock up on some dried fruit (apricots, sultanas, etc) and some nuts and seeds.

I found that a plastic sauce container from the takeaway holds about 30-55 ml of nuts, sultanas etc. I keep one with my snacks as both eating bowl and measure.

Packaging and Portions

Actually achieving the above in practice is a little more complex. Often food is marketed in large packets.

For foods such as rice, sugar and porridge that has a long shelf-life, this is great. For other foods, it is problematic.

For example, the recommended serving for a low-fat yogurt (which may be quite high in sugars) is four tablespoons or 60 ml. It is sold in 500 g pots, with the advice to consume within “three days of opening”. Theoretically, for many households, if this advice is followed, most of this yogurt would be thrown-away rather than consumed.

Many snack foods are sold in large packets, and their is a great temptation to finish the packet rather than consume just a handful.

Bread and vegetables are often sold in plastic bags. These bags retain moisture and encourage food to rot or go mouldy. So you throw it away, waste your money and go back to the supermarket for more.

If you find yourself wasting food (or eating too much!) I suggest you invest in a variety of storage containers.

Remove the plastic packaging from perishable foods and store in containers. It is surprising how much better a lettuce keeps in box rather than a bag.

Some foods keep well in the fridge, others do better at room temperature.

Occasionally, inspect the contents of a box and shake out or mop-up any condensation and excess moisture that has accumulated.

This is also the solution to those large bags of snack food. A sealed storage box will keep them from going stale, and let you enjoy the occasional handful over a more reasonable time interval.

Ween yourself onto healthier alternatives such as nuts, seeds and dried or fresh fruit.

Chop Chop

If you have done any Chinese cooking, you will know that food chopped small takes less time to cook and is less likely to be underdone. This applies to the oven, pot and frying pan as well as the wok.

A palm-sized portion of meat or fish goes much further when diced or sliced.

All the ingredients cooked in this fashion may be served mixed together in a single bowl, which I find makes a meal more interesting and varied to consume. Many of my meals involve just a single bowl in one hand, a spork in the other.

If cooking without vessels, divide your food into small pieces before threading it onto sticks for grilling before a fire. Briefly pass the food through the flames or place it on the coals to sear and seal the outside.

Eat the Rainbow

“Eat the Rainbow” is a phrase I only encountered recently, but nicely summarizes something that I have been practicing for decades.

Consider a meal of something like chicken and chips, which is just yellow and brown or orange. Suppose we make it multi-coloured by adding some sliced baby tomatoes, coleslaw, shredded lettuce, a little onion, some mushrooms. Suddenly this meal has got a lot more interesting and more nutritious.

Not only does such a meal look better, it is also more interesting to eat, with a greater variety of tastes and textures.

Tip: Ramekins (or Gü jars!) are useful for one-person oven cooking.