Recently I have been reading some more Home Guard manuals. Camouflage and fieldcraft were something that the Home Guard took very seriously. They were some of their major defences against the superior firepower of fascist invaders. In previous posts I have referenced “The Home Guard Fieldcraft Manual” by Maj John Langdon-Davies. This is recommended reading to anyone interested in camouflage, not just in the context of WW2 Home Guard. Another notable publication was “Home Guard for Victory” by Hugh Slater. His section on camouflage is only a few pages, but well worth a read. Since this book is not available as a reprint and I have been unable to locate an electronic copy I will take the liberty of reproducing the relevant pages below. If you think your pickup is a little too conspicuous the section on camouflaging cars will be very useful. Many military vehicles could learn from this section.

(Incidentally, I’m very impressed at how well the free “a9t9” OCR software handled the small type in an aged 1941 book!)

CHAPTER XIII CAMOUFLAGE

CAMOUFLAGE WAS ORIGINATED some time in 1915 by a small group of young French artillerymen who in civilian life had been cubist painters and associates of Picasso. As painters they had been experimenting for some years with those problems of form which seemed to them to arise from the work of Cezanne. As light field artillerymen they very soon found themselves to be the bull's-eye for the enemy guns, and they applied their civilian knowledge to the problem of concealing their battery from the enemy's artillery observers.

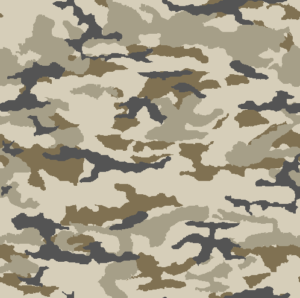

Camouflage covers both concealment and disguise. Any object is seen and recognised first by its form, next by its tone, and then by its colour. The first problem, therefore, is to find a way of breaking up or changing the form of the object you are going to camouflage. Form is indicated to the observer by the shading of the object and the shadows which are cast. To alter the form it is necessary to disrupt and change the normal shading by which the form is shown, and either to eliminate or to alter the shape of the shadow cast by the object. In order to alter the shape of the thing you are camouflaging, disruptive patterns must be painted across its form, using sharply contrasted tones in a line against one another, shading away into one another between. See Diagram 21.

In the distance colour tends to fade, while tones may become more pronounced. Therefore the best way of disguising the shape of an object from an observer at a distance is to use sharply contrasting tones cutting across its shape. All colours fade in the distance, but yellow is the first to lose its saturation, then red and finally blue.

Blue has a greater saturation some distance away than it has near to. For this reason, when camouflaging (for example, a block-house sited on the side of a hill with a wide view, and therefore visible from a considerable distance) the colours used will be yellowish-greys and warm browns with an absolute minimum of blue. Where it is a question of camouflaging an object that we may expect will be seen by the enemy at short range, yellowish colours will not be used, but cold bluish colours will be the most appropriate. In neither case should red be regarded, as a general rule, as a particularly successful camouflaging colour. Pitch black is always very useful.

Obviously the second, though not less important, problem of camouflage, after the question of the disruption of the form of the object has been considered, is to make it merge into, and become part of, its background. Appropriate colours will be used according to where the object is, in a town or in the country. It will be remembered that country colours change quite considerably at least four times a year. In the spring there are yellowish colours, in summer green, in autumn brown, and in winter grey.

In towns, more red may effectively be used. Patterns in towns will tend to be more zig-zag and less curved. Generally speaking white is a bad colour to use in camouflage, but it is not possible to lay down any absolute rules, White could be an excellent way of camouflaging a pill-box in front of a white-painted house in a town.

Light tones are also useful for neutralising any constant dark shadows, such as the shadows at the bottom of fairly deep trenches. In this case, rabbit-netting with fairly light scrim can be most valuable. As a general rule the under sides of objects should be fairly light. In the case of a cubic pill-box the sides should always be painted lighter than the top, and the north side should be the lightest of the four sides, because it is on the one that may be expected always to be in shadow at any hour of the day.

Paint is not, of course, the only way of camouflaging. Very often all sorts of nets and structural methods can be most useful. Symmetry is generally the most obvious giveaway of any position. There is, therefore, every reason why pill-boxes should be deliberately built all sorts of odd shapes. The fact that they are generally either square, round or octagonal is more of a disadvantage than otherwise.

CAMOUFLAGING CARS

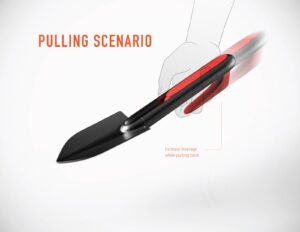

If we apply these principles to the camouflaging of motors, it will be seen that contrasting tones should be painted diagonally across the car. They should be shaded off into one another to spoil the car's form. See Diagram 22.

The roof of the car should, in general, be darker than the sides. The paint used must not shine. Because cars may be expected to be used both in towns and in the country, and at all times of the year, neutral colours should be used. There are, however, on the roads today many khaki cars which, although it is clear that they are intended to be camouflaged, are perfectly obvious, either from the air or the ground, because the tones used are not sufficiently contrasting to have altered or disrupted the tell-tale form to the slightest extent.

The most conspicuous part of any motor car is the shining windscreen. This can be camouflaged by fixing painted expanded metal right across the outside of the glass. This does not interfere to any great extent with the ability of the driver to see out. The wheels and the tyres of a car are also very characteristic and conspicuous shapes which are often neglected, and may give a car away.

From the air, the greatest danger is the shadow cast by the car on the road, which outlines it exactly to the enemy airmen however well the car has been painted. Cars should, therefore, always be parked on the side of the road where there is a broken surface, such as long grass or a pile of stones. Thus the shadow falling on the ground will have jagged edges, and the silhouette will be broken up.

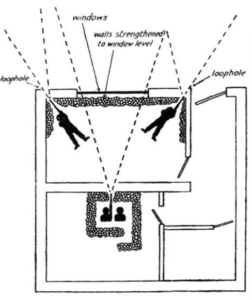

CAMOUFLAGING BLOCK-HOUSES

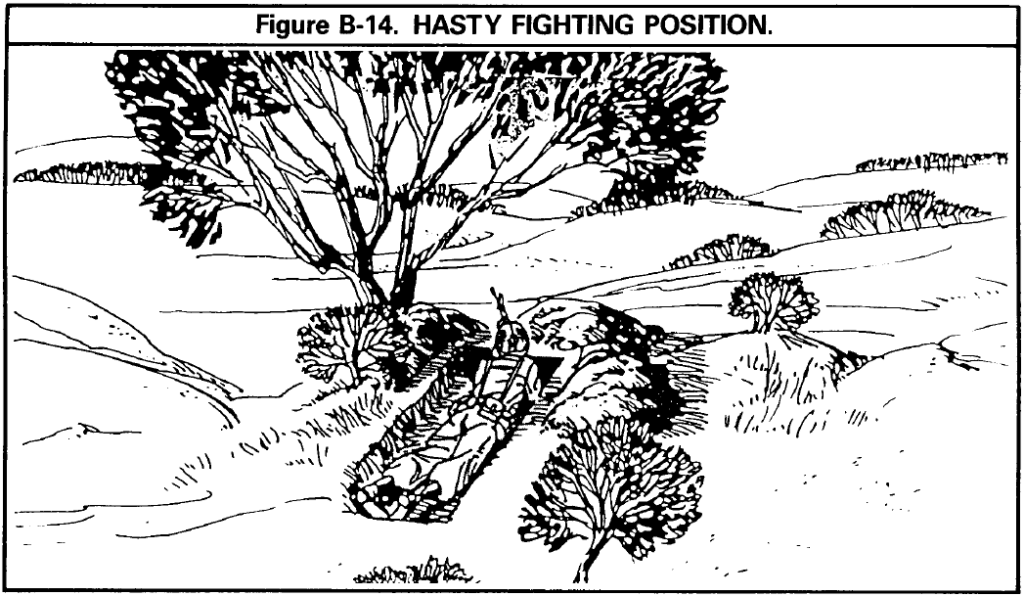

First of all, the block-house must be toned and coloured to merge with its background. It will, however, be remembered that we have got to assume, under modern tactical conditions, that the enemy may approach from any direction. From different angles, the background for a particular block-house may be completely different.

This means that camouflaging such positions is very far from a simple matter. The first thing to do is to spoil the block-house's symmetrical shape (although it ought not to be symmetrical, it nearly always will be).

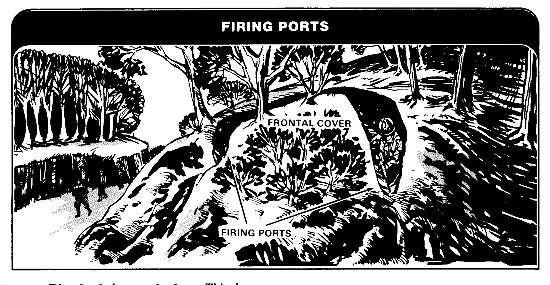

This can best be done by leaning bits of wood-railings and sticks up against it and destroying its silhouette. The loopholes of a block-house will always look like pitch-black rectangles from the outside. Therefore rough black patches should be painted across the loopholes. See Diagrams 23 & 24. Another way of disguising loopholes is to hang netting with light scrim across them.

To the aerial observer, one of the most obvious ways of spotting block-houses, or an artillery position, is to look for worn tracks and footpaths that seem suddenly to end, or for two or three of them that converge at a given point. It is all too easy to make the mistake of wearing a track up to your block-house, because the occupants will naturally tend to come and go the same way, One way of handling this is deliberately to hoe up behind the blockhouse, an artificial path, continuing the real path, so that it becomes, to the airman, a perfectly innocent footpath from one side of a field to the other.

PERSONAL CAMOUFLAGE

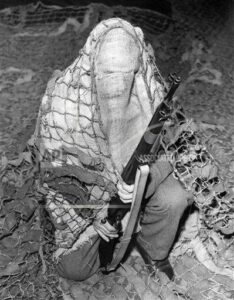

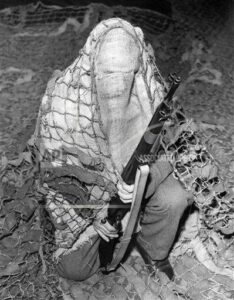

When considering the camouflaging of a scout or a sniper, it will be remembered that his most conspicuous parts are his steel helmet (which is symmetrical and shining) and his face, which, however sunburnt, is always very light in tone. His hands are also conspicuous. The helmet must be painted a matt colour, and disruptive black stripes may be drawn across it. Another way of camouflaging the helmet is to buy at a ladies' hairdresser an old-fashioned hairnet or snood, into which feathers and bits of rag may be fixed for scrim. For raiding parties at night faces and hands should be made black. This can be done either with burnt cork or, better still, with grease paint. During the day, patrols likely to run into danger may find it useful to draw a black stripe across their faces with grease paint. A more simple means of covering the light tone of the face, particularly for anti-aircraft riflemen, is the use of an ordinary khaki handkerchief folded into a triangle and tied across the face just underneath the eyes, covering the whole of the lower part of the nose and the mouth, chin and ears. See Diagram 25.

CAMOUFLAGING BRIDGES AND RAILWAY STATIONS

Because it is almost impossible to conceal the tracks leading into a station, or the river over which a bridge runs, it is difficult to prevent the enemy pilot from finding the bridge or station he is looking for. A determined enemy, prepared to make sacrifices, can, by diving low, secure the necessary direct hits-always presuming that he can see the object he is aiming at. To camouflage bridges or stations, therefore, a method must be found which makes it impossible for the enemy to see his target. Probably the best solution of this problem is to put up a smoke screen over the bridge to be protected. The generators should be placed in a circle at a radius of about half a mile from the bridge or station, and ignited along a segment on the windward side of the vital point. In this way an opaque screen one square mile wide can be placed between the bomber and his target. It would be impossible for him to score direct hits except by the most extraordinary good luck.