In Tom Wintringham’s “New Ways of War”, he states that the first lesson to learn is how to take cover. That is pretty good advice in general!

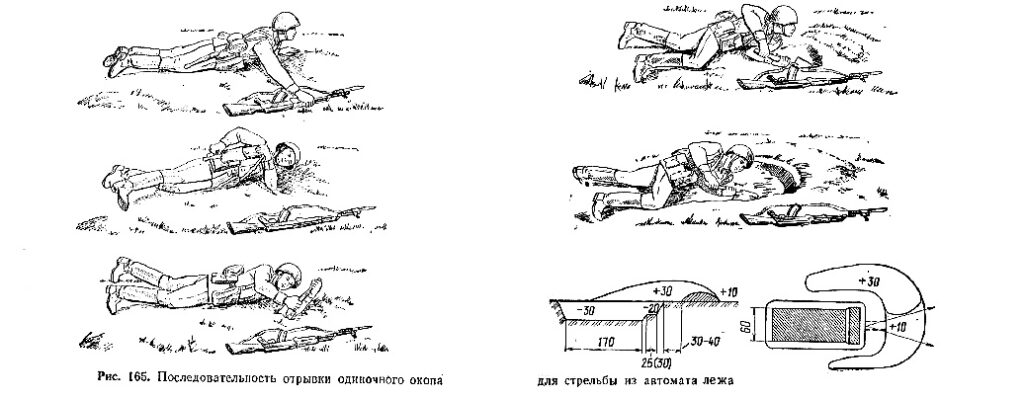

Recently I was thinking about entrenchments. When a soldier halts and expects the enemy, he is supposed to create a shallow trench he can lie in. This rendition of a Soviet soldier nicely illustrates the process:

Military men often have a tendency to try to refight previous conflicts. Things get done a certain way because that is the way they have always been done. This may fail to take account of changes in tactics or technology.

In some 1940s field manuals one can detect concerns that about the vulnerability of entrenchment systems to contemporary artillery. It is suggested that attention should be paid to camouflage to prevent them being targeted.

Within a few decades we are likely to see weapons that can recognize and specifically target foxholes and weapon nests. They may even be able to distinguish those that are occupied.

In the modern era of aerial and satellite reconnaissance, hiding the location of entrenchments is problematic. There is little point in camouflaging the final position when the construction process has been observed and logged. Extensive entrenchments may only be practical if constructed in covered areas such as urban locations or woodland.

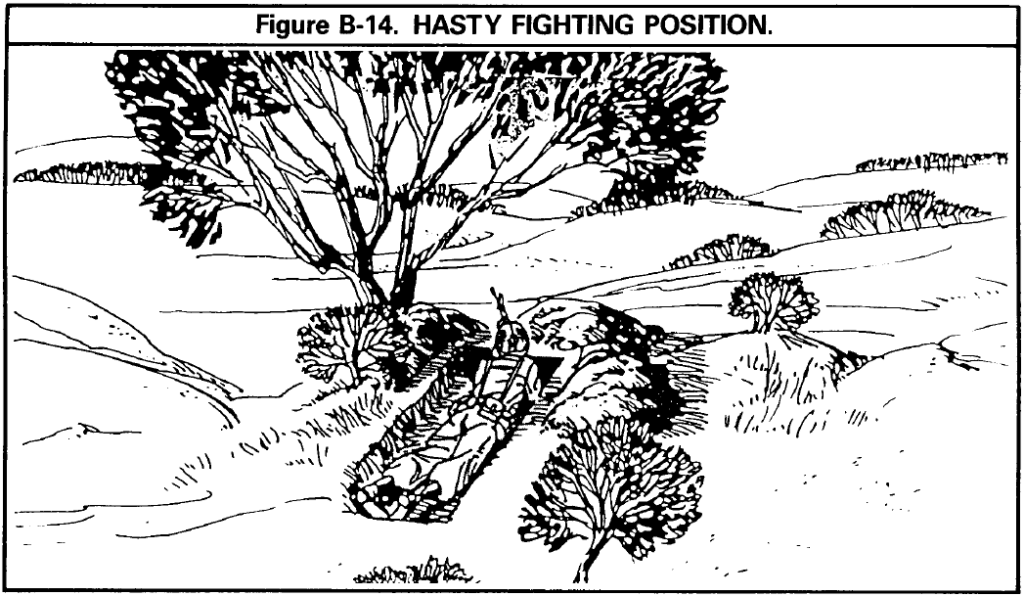

In more practically orientated forces, hasty entrenchment may be more usual.

Hasty Entrenchments

There is an implication that the trench should point in the direction of the enemy.

In actuality, the trench may be orientated so the soldier can fire obliquely, with the majority of the dirt placed between him and the enemy’s approach.

The hasty trench is about half a metre deep, as wide as the soldier needs and has one end constructed as a firing position with elbow rests etc.

The earth mound should be about 1.5 metres/5 feet thick to deal with bullets such as the 7.62 x 51 mm and 7.62 x 54 mmR.

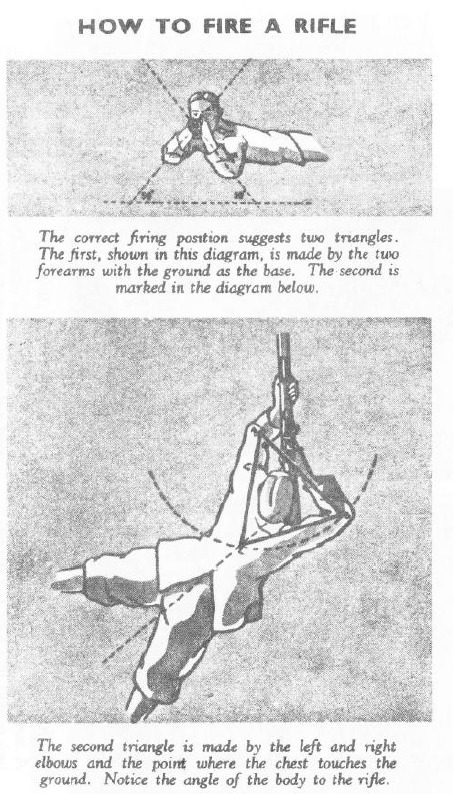

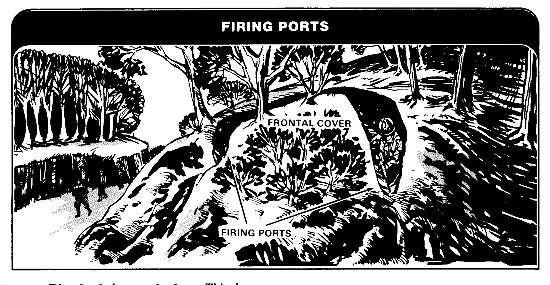

This illustration from an American field-manual better illustrates the latter point. The prone position is the most stable firing position so should be used whenever possible. Many of us are not symmetrical in our most comfortable prone position so the angle of your shallow trench should reflect this if possible.

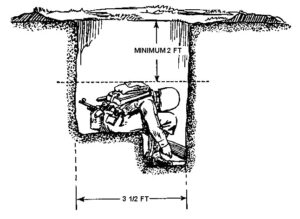

In theory, a soldier should continue to dig his hasty firing position, deepening the hole to make a kneeling and then a standing position.

The position is constructed so the soldier can still rest his elbows, so theoretically a foxhole is a better firing position than standing or kneeling when in the open.

Deliberate Firing Position

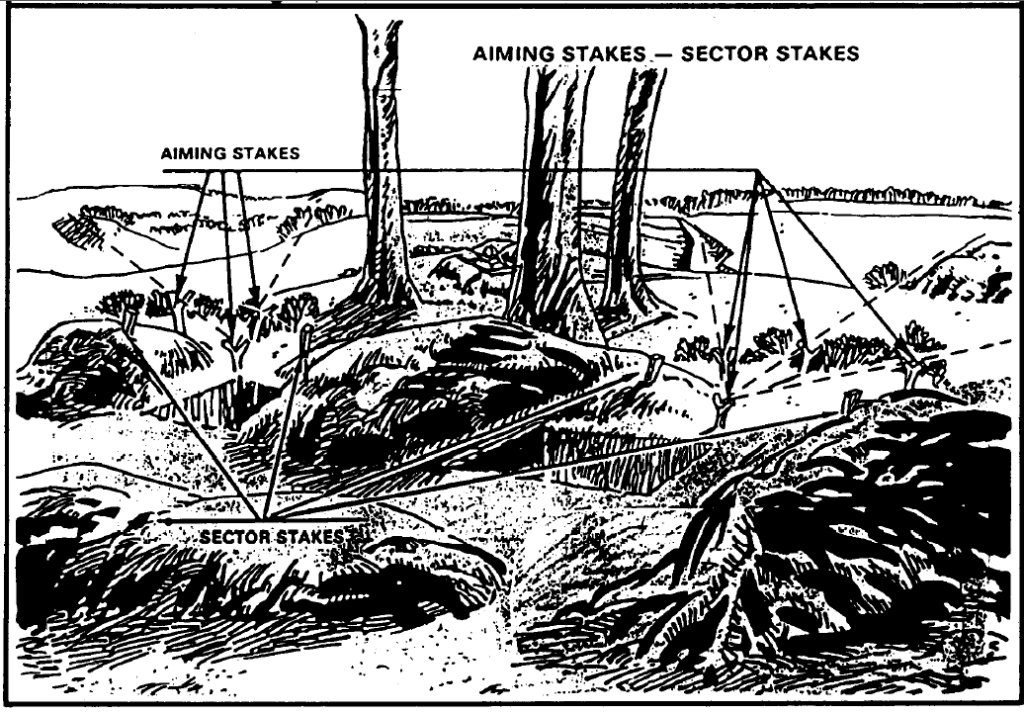

Field manuals show what a “deliberate” fighting position should look like.

Typically, it is a rectangular hole perpendicular to the line of enemy advance. Turning a shallow hasty position into such a construction seems to involve a lot of earth moving!

Improving the Hasty Position

Perhaps there is a better way?

Once you have dug your hasty prone-firing position and camouflaged it, leave it alone! Instead, ramp the rear end downwards and construct a slit trench, 60-75cm wide and 1.5 metres deep. Given time and materials give this overhead cover. Creating a seat means less earth to remove and this can also serve as a fire-step.

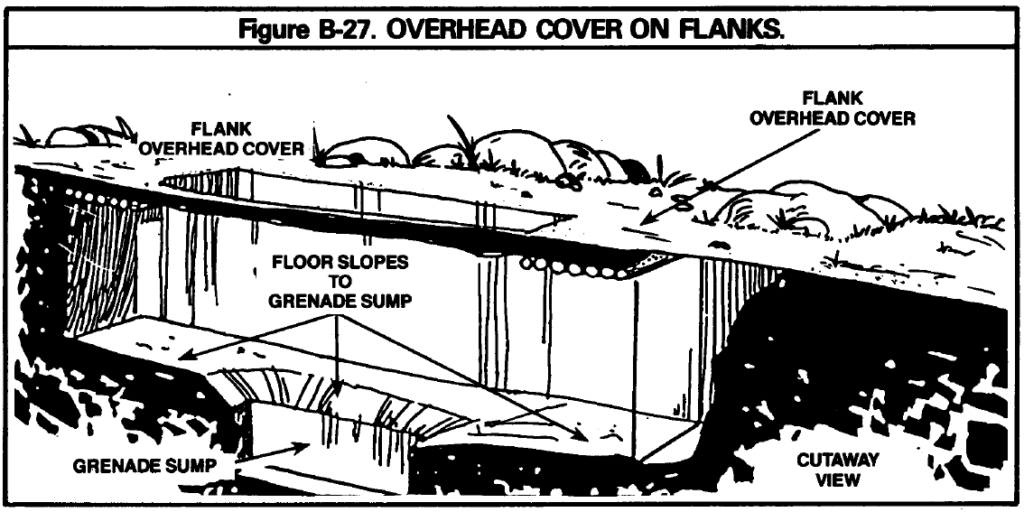

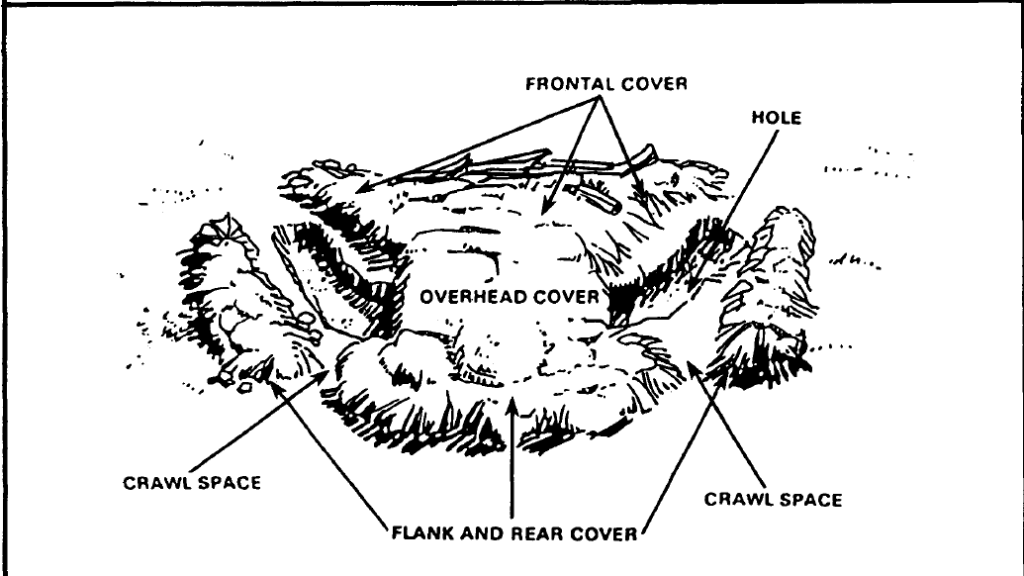

The illustration below shows something along these lines. Two prone-firing positions have been extended back and down and the deep area provided with overhead cover. This works well on a slope.

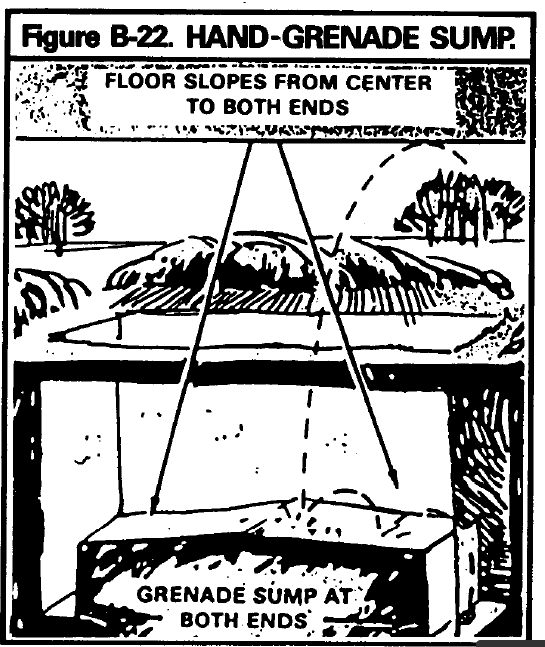

A variation is to dig a pit about 2 metres deep at the foot of the prone position. This acts for drainage. The slit trench is then dug radiating out from this well.

This method allows for vagaries of the terrain and creates a less regular shape when viewed from the air. The slit trench can be extended to create a communication trench if needed.

Below is a WW2 example. A relatively shallow fighting area for the infantry gun. Deeper, narrow armour protection/slit trenches to each side.

This approach provides a protected firing position and a deep protective shelter against bombardment and armour.

It would be interesting to do some time and motion studies to see how this method compares to the traditional “make everything deeper” approach.

It should be remembered that digging deeper is proportionally more labour-intensive than a shallow digging. Considerably extra energy is expended moving the earth up out of the hole. This is even more problematic if the soldier is working alone or lacks a container such as a sandbag or bucket.

Loopholes

The above raises another question.

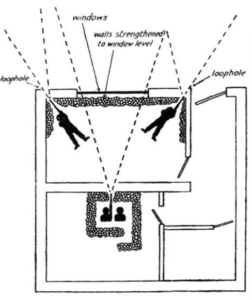

When loopholes are made in buildings, they are usually positioned so that a standing solider can use them. Given a prone position is superior, would it not be more logical to cut them lower in the wall?

Building windows are naturally targeted by enemies, so loopholes at the same level are more likely to catch stray rounds. Placing the loopholes lower would reduce this. Also, loopholes at skirting board level are much easier to cover with a sandbag or two when not in use. Something to ponder!

The image above is from a Home Guard manual. Note the two corner men are prone and this allows more efficient strengthening of the walls. The MG team fire out the window, although they are positioned behind an interior wall and use a loophole.

Ideally, wire defences prevent an enemy getting within grenade range of the house. This is seldom practical.

Low loopholes should have a small trench below them outside. Grenades that hit the wall and fall down will explode in the trench beneath the level of the loophole.

Hasty Positions and MRE Boxes

“I hate digging fighting positions, I really do. hate it with a passion. Particularly those full length armpit-deep types. Why? For the same reasons as you. It takes damn too much work, too much time, and too much out of you. And by the time you get around to completing yells, 'Let's go! Fill'er up, pick'er up and move out! Am I right or wrong?

Don't misunderstand me, I know the purpose of a fighting position, they're to protect against small arms fire, indirect fire (art, mortar & fragments), tanks, etc. They're designed to give a defender a better chance of survival during an air or ground attack when the bad guys want to take over your estate property.

As a Ranger. I only believe in hasty, prone, dug-in fighting positions versus those armpit deep ones. Why? Well. just because they're easier. faster, and take less strength to build. But because a soldier can rest and shoot better in a prone position than a standup arm-pit deep position. How in the hell can you sleep standing up? You obviously either have to crawl out of it to sleep, or dig another position just for your sleeping gear, right?

Every time our unit was told to dig in, I didn't question or ask, "What type?" I instructed my men to start with the hasty prone position until they're told differently. If the Commander or 1 SG didn't come by to check up on us, we were good to go! If we were told to go all the way- (AIRBORNE), we just continued digging.

But you know what, it's too damn bad that the MRE cardboard box doesn't come in another color. Wouldn't it be nice if half the box was woodland camouflage and the other half desert camouflage? You just turn the box over to match the surrounding terrain. side you don’t is the part that's facing down or in towards you.

Would it work? Why not? You'd only have to fill up boxes with dirt or rocks and start sucking. You could build a bunker Or even a defense wall, they'd be as good as any sandbag, and be like playing with toy building blocks except bigger. [see “gabion”] But they wouldn't be water proof unless a chemical was added to make them water resistant.

The MRE box would also be a lot easier to dispose of in the field. Troops would fight over boxes because they know it would save them time in digging a position. Think about it, as you fill the boxes with dirt, you're also digging a hole. You wouldn't have to dig down far like a regular armpit fighting position. What do you think?”

Ranger Digest IV, p.66

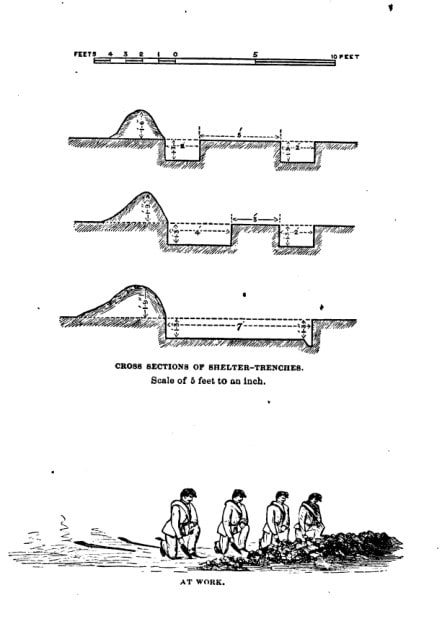

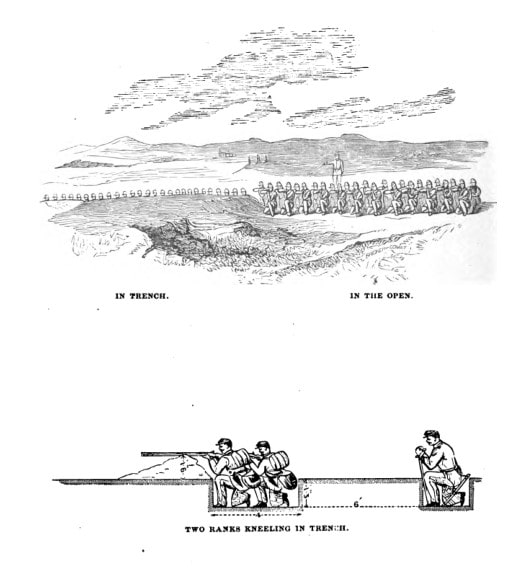

19th Century Hasty Positions

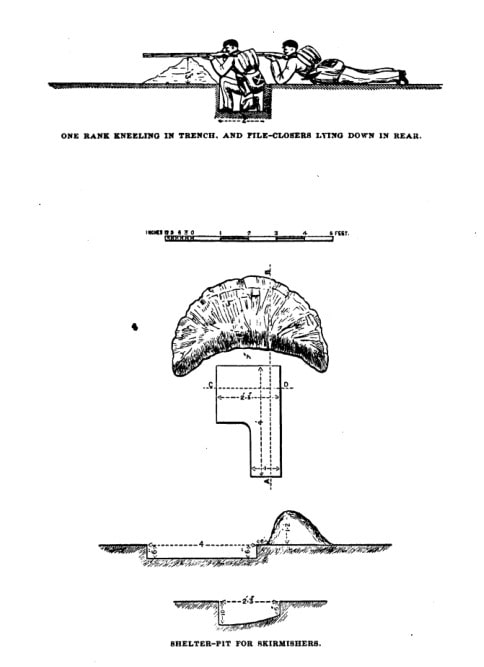

The 1870s trials of Rice’s trowel bayonet mention earthworks thrown up in under twenty minutes. At the end of the report is an attached circular instructing troops how this may be done, and some illustrations.

“The soldier should dig a hole six or eight inches deep, and about twelve inches in width across the top, scraping the earth out to his front; he should then thrust the bayonet into the ground from four to six inches toward himself, from the edge of the hole, pressing it downward, and working the bayonet from right to left, so that the edge of the weapon will cut through the tough sod or other surface.

The blade of the bayonet having been thus worked into the earth some six or eight inches, it will be pressed forward (using both hands at the handle), thus breaking off large pieces of turf, or other compact earth.

The soldier will work in this way, moving backward, until he has broken the ground from three to five feet from the edge

Of the hole; he will then turn or face to his right, take the point of the bayonet in his left hand and scrape all the loose earth to his left, the bayonet pointing from him, making there with a parapet to the front. If the ground is such that after having thus worked backward some three or four feet the men are still in line, the odd or even numbers should be directed to turn to their right, and scrape the earth toward and upon the parapet; this, however, will depend upon the kind of soil in which the line may be working.

A few trials will teach the men the best methods of working and of aiding each other in different soils.

While the men in ranks are busy throwing up the work, the sergeants, or file-closers, should be placing any available obstructions on the work to strengthen it, as logs, Stumps or fences, or may cut sods for-loop-holes, or collect branches to plant on the parapet for a screen ; and, if the trench be thrown up on grass, may cut turf to cover the parapet, so that it may not be distinguished at a distance.

If such materials be abundant enough to render it advantageous, the rear rank, or a portion of it, or if in one rank, certain sets of fours or numbers, may be directed to aid in this portion of the work.

In this way the intrenching would be carried on along the whole front, with the assistance of all the soldiers…

…The trowel bayonet requires the digger to work on his knees. This is but a slight drawback when the work is of short duration, and it is even an advantage when it is being carried out under the enemy’s fire as a man offers in this way a smaller mark for bullets and shrapnel.

Although but little used to earth-works, infantry soldiers who do not work long enough to get tired will attain a great rapidity of execution for it will be to their interest get quickly under cover.

Skirmishers Making Shelter-pits.

Men skirmishing should be able to make cover for themselves. In most instances the men will only have to improve natural cover, but it may be necessary to dig small pits, and each be for one set of fours or for one man only. In a few minutes he can in this way render himself almost entirely safe from the enemy’s fire, and at the same time aim correctly, using as rest either both his elbows or his left one only.

After a little practice, each man will soon ascertain the exact form of pit that suits him.

The depth need not be uniform, should be about ten inches where the man’s body will be, and about six inches in the other parts.

If time admits, a small mound of earth may be built up on each side of the spot on which the barrel rests, order to give cover to the head, or the parapet may be made thicker and the trench deeper. Natural cover should always be taken advantage of when possible. Sometimes it will suffice of itself; sometimes it only wants a little improvement.

It is a known fact that a well-protected skirmish line can easily drive back a line of battle.”