Many thanks to Ric Morgan for his donation to support the blog.

Recently I got to thinking about archery. In particular, I was curious about the time of flight of arrows and quarrels. This seemed quite a practical thing to know. I was a little surprised at how little information on this could be found on the internet.

Most modern archers are target shooters, so not particularly interested in how long the arrow takes to reach a static target.

They also shoot at ranges that provide very little insight into, say, bows being used on medieval battlefields.

If you play role-playing games, arrows probably hit in the same turn, which may be the same second, of firing.

You would think there was considerable discussion of flight times among bowhunters, but not according to my search engine.

One target site did inform me:

“Recurve bow arrows can travel up to 225 feet per second (fps) or 150mph while compound bow arrows can travel up to 300fps (200mph). Longbow arrows travel slower due to the weight of the arrows. Even at 300fps, it takes around a second to reach a 90 metre target. You hear your release first followed by the thud of the arrow hitting the target a second later (you can’t see it unless you use a telescopic sight).”

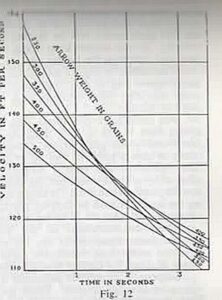

More trawling found me this article, with the following table:

I also remembered an old book I had, which gives the following table:

90 metres in the first second sounds like a good rule of thumb, although I would like to know how this changes beyond this range.

Why does it matter?

If in an emergency situation a bow may be one of your options for defence or food gathering. Much of the information relevant to arrows will also apply to other hand-thrown missiles such as spears or rocks.

Contrary to what you see in action movies, bows are not “silent killers”. Some of the energy stored up in a drawn bow is released as sound.

Your arrow will travel at 100-200 fps, while sound travels at about 1,100 fps. The animal you are shooting at will hear you before the arrow arrives. Many animals survive by being paranoid, so there is a good chance it will begin moving before your arrow arrives.

Thus, you need to lead your target. For this, you need to know time of flight. Calculating lead and other parameters is covered in my book on survival weapons.

While there was very little discussion of time of flight, it seemed initial velocity and kinetic energy seemed to be of great interest to bowhunters.

The V0 of a bow is the equivalent of the muzzle velocity of a gun. Most bows don’t have muzzles.

Arrows lose energy at a pretty steep rate. One of the above sites uses a working figure of 3% per 10 yards. This means that the terminal velocity of an arrow is going to be very different from the V0. Failing a really strong tailwind, V0 is the one velocity your arrow will not be at!

As discussed elsewhere, kinetic energy is something of a red herring when predicting bullet performance. It is popular in the gun press. It is far more impressive to say a round has 2,352 ft/lbs of energy than that it has 1.7 ftlb/sec of momentum!

Terminal performance of arrows is somewhat easier to estimate than for bullets. Arrows mainly rely on cutting to produce blood loss.

Given similar size and configuration of arrow heads, it seems reasonable that the more effective arrow will be that that penetrates more. Just for fun, I ran some figures using the following formulae:

Energy (ftlbs) = [(Velocity (fps))^2 x Weight (grains)] ÷ 450,240

Momentum (ftlbs/sec) = Weight (grains) x Velocity (fps) ÷ 225218

From the above chart, I selected a 450 gr arrow at 130 fps and compared it to a 350 gr arrow at 147.4 fps. These would both have a kinetic energy of about 16.89ftlbs. Since weight is different, so will momentum be.

The heavier arrow is at 0.2597 ftlb/sec while the lighter is 0.225 ftlb/sec. That is about 15% difference.

One would expect the arrow with more momentum to penetrate more due to its higher inertia, but would the difference be significant in real world applications?

Something to think on.

Bow length varied with tribe, intended use and probably the individual. Bows of six foot or longer were known, as were bows of only a few feet. A suggested measure for a bow was the distance from the left hip to the right hand when the hand was held out horizontally to the side. This is about four feet. Some readers will recognize this as

Bow length varied with tribe, intended use and probably the individual. Bows of six foot or longer were known, as were bows of only a few feet. A suggested measure for a bow was the distance from the left hip to the right hand when the hand was held out horizontally to the side. This is about four feet. Some readers will recognize this as