I have talked about using Claymore mine bags to carry ammunition on a number of instances. I was therefore intrigued by this idea from 1943, called the “Brooksbank” method. All credit to Karkee Web for the images and information:

Method of wearing the fighting order (See Fig. I)

(a) The gas cape folded flat, about 10 in by 12 in, is put on first in the normal manner.

(b) The small pack is slung over the right shoulder and the two valise straps fastened (firmly but not tightly) over the stomach with the bayonet and frog on the right hand side, slung on the valise strap.

(c) The respirator is put on in the reverse alert position, i.e., the haversack goes on the back resting on the gas cape with the sling (shortened as far as possible) on the chest, with a piece of tape on each lower " D " on the haversack coming round to the front and with the left tape underneath the brace, through the sling, fastening on the right with a slip knot. (The right tape therefore will be only approximately 4 in to 6 in in length).

Commentary

Some clarification is in order. The “gas cape” or “anti-gas cape” was a protective garment against chemical warfare agents such as mustard gas. It actually resembled a long, sleeved coat rather than a cape. The model in use in 1943 was provided with long tapes so that the rolled garment could be carried across the back of the shoulders. No webbing was needed to carry the cape in this fashion. In the figure on the reader’s right in figure 1 the tapes of the cape can be made up coming up from under the soldier’s armpits and disappearing behind his neck. The cape could be quickly unrolled down the back and put on without unfastening the tapes. An excellent source of information on these items can be found on this video.

What is possibly not made clear is that the small pack would spend most of its time across the small of the back, and would only be pulled around the side when ammunition or other items were wanted. A photo of how just the pack would be worn is shown on this page.

The Brooksbank method was supposed to save weight. While it does away with the ammo pouches, belt and water-bottle carrier, the soldier still carries his standard haversack contents, plus finding some room inside for carrying individual and squad ammunition. Although called a haversack, not many of the recommended contents  of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

Many of these items should probably have been left with the truck rather than being carried into combat. I recently read a 1940s manual on street-fighting and soldiers were told not to bring their haversacks into action. Urban environments had plenty of shelter so groundsheets and gas capes were not needed. Haversack items that might prove useful could probably be carried by other means.

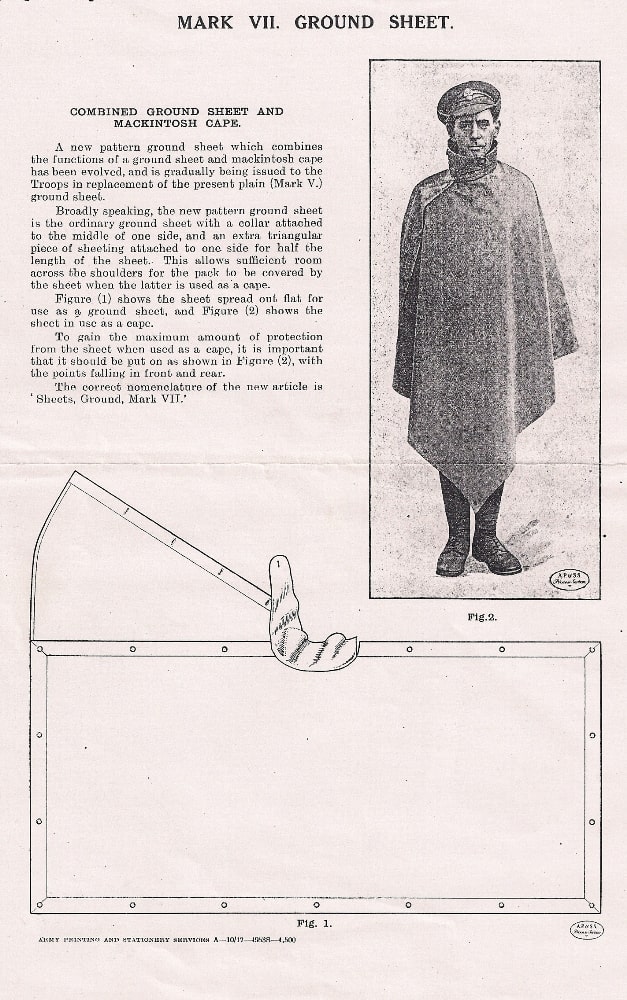

The groundsheet carried at this time is of interest, since this would probably be of some variety of MkVII, and was designed to also act as the soldier’s rain protection. The gas cape was supposed to be reserved for the event of chemical warfare, but in practice might be used as a raincoat.

Many years ago, I travelled down Italy, my belongings packed in a sports bag. At one town I had to walk longer and further than usual to located accommodation. Even though I could swap over the shoulder I carried the bag on the uneven weight caused me to sprain one ankle, resulting in a rather painful couple of days. Since then I have always used rucksacs. I don’t know if that would have been a problem with the Brooksbank method, but do feel more though should have been given to what was carried, as well as how.