There are a number of shooting systems that claim to utilize a shooter's “natural pointing ability”. While these systems seem to work, I will admit to having been a little skeptical as to just how inherent or accurate such pointing abilities really are.

Today I found an explanation that seems answer some of my doubts.

The writer explained that when you point at something the finger does not necessarily line up with the eye. Point at something and then move your head so you can look down your finger. You will find your pointing ability is much more accurate than you might have expected.

Learning this is rather timely, since this week I read “Shooting to Kill” by Andrew G. Elliot. Shooting to Kill is a manual written for soldiers and home guardsmen in the 1940s.

These include the “Quick Kill” methods based on the book “Shooting to Live” by Fairbairn and Sykes.

“Shooting to Kill” nicely complements the latter work, and not just in the symmetry of the titles!

The Quick Kill method can be described as locking your attention on your target and firing as your gun raises up into your field of vision. Shooting to Kill is written for riflemen but uses a method derived from the shotgun techniques developed by Robert Churchill.

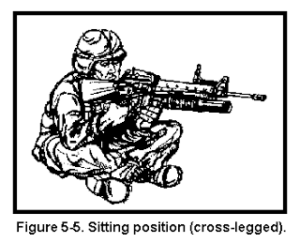

Lock your attention on to the target, or more specifically the part of the target you intend to hit.

Raise your rifle to your shoulder and fire. This is done without trying to (consciously) acquire the sights.

Look, point and fire.

The body, support hand and eye are directed toward the target. The support hand fine tunes the muzzle's position.

The sights can be used if there is sufficient time, to “fine tune” the initial pointing.

If your shouldering action is sound, your eye should have naturally assumed a position where it was looking through the aperture rearsight at the foresight.

The brain automatically centres the foresight in the field of view.

If using a “U” rearsight, the eye should have assumed a position where it was looking across the rearsight at the frontblade, the top of the blade level with the top of the U.

Elliot notes that for most shots the sights are unnecessary if you have mastered this method.

Elliot notes that a rifleman is unlikely to engage targets beyond 300 yards so advocates that the battlesight be used exclusively in combat.

Like many of his contemporaries, he notes that a shooter has little need to concern themselves about the effect of wind, distance or rain at the combat ranges they will be shooting at.

Elliot on wind allowance: “The inexperienced will have heard much about allowance for wind, and the effect of rain on the bullet’s course. These factors can be ignored. In war, most shooting is at 300 yards or less, and at that range, wind or rain have no perceptible effect. In theory, with a strong wind, at a couple of thousand yards, aim should be taken a few feet to the windward, but in practice, except at very long ranges, it is better to ignore this academic principle.”

Traditional shooting ranges were only for zeroing and teaching the very rudiments. All other rifle practice should be combat orientated.

Elliot remarks that he gets respectable scores on the target range without using his rifle's sights.

The key to the technique that Elliot advocates is that the process of shouldering the rifle be sound and consistent.

The soldier or guardsman should often practise shouldering and pointing the rifle, for as much as an hour at a time. He notes this is also a very practical way to build up arm strength.

A firefight is no time to be guessing at target speeds and calculating leads.

Elliot suggests that moving targets be engaged with what would be called a “swing-through” of “smoketrail” method in more modern parlance.

Track the target and increase speed to swing past it and fire just ahead without halting your motion. Aiming point against moving targets was “the tunic buttons”. This automatically shortens the lead if the target is approaching at an angle.

Elsewhere he suggests the belt buckle as an aimpoint. Since soldiers often shoot high one can see the wisdom in this. A lower aim is also needed if a target is charging towards you or at a higher or lower elevation.

Some of the advice in this book needs to be taken in context.

Against an enemy firing over cover, an aimpoint several inches below the top of the cover is suggested.

The .303 rifles of this time had a battlesight zeroed to 300 yards, giving a maximal ordinate of seven to eight inches.

The .300 (.30-06) P17 used by the home guard had a battlesight set for 400 yards, giving a max ordinate of twelve to thirteen inches.

Thus a head shot at shorter ranges needed a significant hold under. More modern cartridges with a 200 metre zero will behave differently.

The book gives advice on a number of other matters.

When engaging low-flying aircraft, he suggests a lead equivalent to the distance between the forefinger and little finger tip of a spread hand held at arm's length. This is about ten to twelve degrees, which is about right for a target moving at around 200 mph.