Recently I have read books by Tom Wintringham, Bert Levy and John Langdon-Davies. A topic common to all three of these is the visibility of the human face.

If a soldier hears an aircraft overhead it is understandable that he might look up at it. An uncamouflaged human face is visible from a considerable distance so a pilot may observe his observer. Now imagine a company of infantrymen all looking up at an aircraft. Effectively this would be a sudden white flash saying “here we are!”

I recently read that “the secret to invisibility is to freeze like a lizard on a rock”. If an aircraft or other potential threat appears one should take cover if there is any nearby, freeze if there is not. Keep your eyes down on the ground. Only one or two men should observe the aircraft, and then only with adequate face camouflage. In a previous blog post I described a simple framework that could be worn on the back or the pack. These were used by the NVA and Viet Cong when on the march. Any time an aircraft appeared overhead they would drop to the ground and become bushes. Incidentally this also illustrates that marching formations should be irregular.

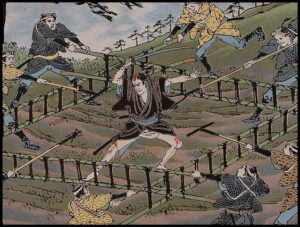

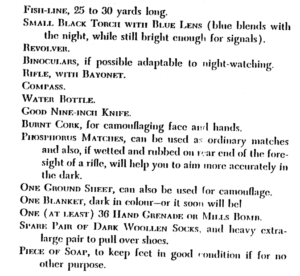

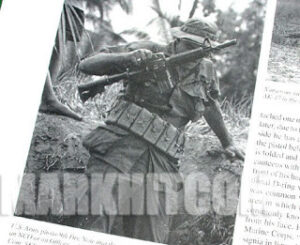

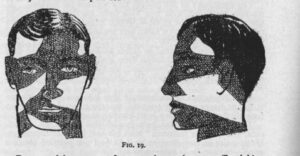

The following image was scanned from Langdon-Davies’ book.

Langdon-Davies notes that eyes are very distinctive and that many animals have colour schemes that make their eyes less noticeable. Often this takes the form of a line, stripe or blob that runs across the eye. Logically, he advocates that a human soldier’s camouflage should do the same. The human nose is another prominent feature so this needs to be shaded to compensate for this. The scheme he proposes was using a single colour of camouflage, such a burnt cork. It was sufficient to disrupt the palest skinned face. Nowadays multi-coloured camouflage kits are common.

Camouflage creams may have advanced a bit but I have to question if the principles Langdon-Davies had described are being observed. It is not sufficient simply to get the face dirty or paint stripes across it. Prominent features such as the eyes and nose must be disrupted. Features that catch the light must be darkened and areas that are shaded must be lightened.

Langdon-Davies was writing for a primarily Caucasian audience but his comments also apply to other skin tones. Human skin can be reflective so needs dulling down. Blue eyes can be distinctive. Shade from suitable headwear can help.

While painting the face can be effective there may be situations where you will need to rapidly remove any facial camouflage. Face painting can be combined with other measures, of course.

A tight-fitting face-net can be distinctive, defeating the purpose of the item. Face-nets or similar devices should be relatively amorphous. In a previous post we saw a face-veil used by German troops. While this was effective it was apparently impossible to run with this fitted. Such factors need to be considered if you have a mobile role. At night a net across the eyes may hinder vision to an unacceptable level.

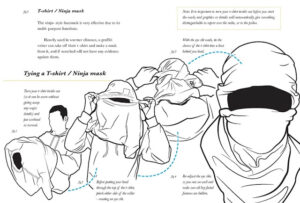

One of the simplest ways to conceal the face is a scarf or bandana across the nose and mouth. Folds in the material help disrupt the shape. Since the face area may be shaded by headgear I’d go for a relatively light coloured material with contrasting disruptive blobs. As I have suggested in previous posts, children’s clothing or cheap t-shirts can be an economical source of camouflage material.

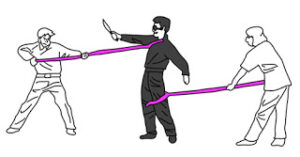

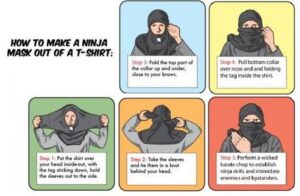

Even if you have correctly painted your face a cloth across the nose and mouth has other advantages. Facial recognition software has become commonplace in the last few years and we will undoubtablely see applications of it more lethal than the camera in your phone. A cloth across the nose and mouth also softens the sound of your breathing, which was one of the reasons the ninja favoured this. A ninja’s disguise might be a simple bandana and scarf. The bandana is folded diagonally and worn over the hair. The scarf is pulled across the face and tucked up under the bandana. When not worn there would be nothing particularly suspicious about these items.

Make a web search of “ninja hood t-shirt” and you will find numerous sites and illustrations of how to make a ninja hood using a t-shirt or sweatshirt. Many of these are tongue in cheek but it should be apparent to the reader that if you use a shirt with a suitable camouflage pattern you may have the beginnings of something quite practical. Add some scraps of scrim and hessian to further disrupt the shape.