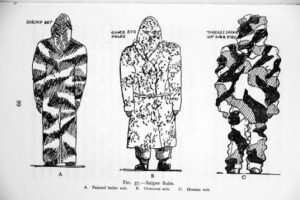

This establishes that khaki (beige)/drab uniforms had been adopted for their resemblance to mud or dirt rather than vegetation.

Further down were two intriguing extracts:

The article from The Times reports some experiments performed to study the effect of uniform colour on visibility. The term “camouflage” would not be coined until the First World War.

A tunic of scarlet, blue or green would be worn with the dress uniform and one of grey used for undress and active service.

More practical might have been to issue the home service helmet in grey and have a more decorated cover for parade wear.

I have been unable to determine how light a shade of grey this was, nor if it was a “warmer” or “cooler” grey.

The suggestion that existing white equipment be stained with an umber solution may imply that it was a warmer shade.

The shade of brown the equipment would have dyed is also unknown. Presumably this was of a similar shade to the grey.

I like the thought that evidently went into this report. Since grey will go with nearly anything, a smarter uniform can be created by just changing tunic colour.

The second extract (shown first on the original page) is an account of a discussion in the House of Commons that predates The Times article and may have inspired the experiments reported.

Soldiers of the Rifle Brigade are described in the report as wearing black when their uniform is actually dark green with black equipment. Although the dark green rifle uniform is often attributed to being a form of camouflage, it was unlikely to be so in practice in terrain other than dark forests.

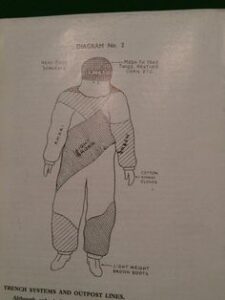

Of particular note in this extract is the discussion of poorly designed uniforms that restrict the soldier.

Jump forward to just before World War Two and you will hear similar discussions.

Then again in the 1970s and 80s.

And if we now look at modern combat wear, we still see overly tailored uniforms that restrict movement, air-circulation and provide poor camouflage.

There were, apparently, some efforts to adopt grey uniforms and in at least one campaign both khaki and grey were used by the British Army. Note that some illustrations show combinations of grey and khaki. Also note references to stained “off-white” equipment.

Shown above is a Coldstream Guards uniform from the Sudan campaign.

The suggestions about dying white equipment seem to have been only partly observed, however, and presumably buckles and buttons were still polished.

It is worth noting that later designs of military uniform covered buttons with a fly front, like a paletot coat.

Indian-based units (the greater part of the British Army) seem to have already adopted khaki.

Khaki uniforms seem to have been cotton drill, while grey were woolen serge.

Which would have been adopted would have been of considerable economic interest to the cotton and wool producers of the Empire.

Wool production was mainly within the British Isles, while cotton production was in the overseas areas of the Empire.

History suggests the cotton growers had the more influence.

So, with a few twists of fate, the familiar image of the Victorian soldier in khaki with white equipment might have been in grey, with umber equipment and bronze buckles.

Perhaps the army might have adopted grey serge for temperate climes and cotton khaki for hotter postings. Or use grey trousers and greatcoat with a khaki service tunic.

Some other armies of the time issued “summer” and “winter” tunics, often of different shades and cloth types.

The Times of March 29th, 1883:

THE COLOUR OF ARMY UNIFORM

The report of the Colour Committee appointed by the Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief to consider and report what colour, suitable for military uniform, is least conspicuous, was published yesterday as a Parliamentary paper. The Instructions given to the Committee were as follows:

"Having regard to the increased range of rifled arms and the consequent exposure to troops to fire at great distances, that exposure of troops to fire at great distances, that exposure continuing and being enhanced as they approach the enemy, it is desirable that Her Majesty's forces on active service should wear uniform of the colour ascertained to be the least conspicuous.

"It is observed that the use of a neutral colour – Khakee – is general in India, and at the same time that at least four colours are generally worn by Her Majesty's troops elsewhere, each of these (except, perhaps, in the case of the green worn by the Rifles) having been adopted without reference to their greater or less visibility.

"It appears, under these circumstances, desirable that, in the first instance, before the question is discussed with reference to other considerations, a scientific enquiry should take place as to the comparative visibility of different colours suitable for military uniform in the field.

"His Royal Highness has recommended to the Secretary of State that two or more persons of undoubted scientific authority on the question of this character should be invited to co-operate with a small number of officers with a view to carry out any practical experiments which may be necessary for the complete discussion and utilization of known facts on this subject.

"A committee composed as follows: President. – Lieutenant-General Sir. G.J. Wolseley, G.C.B.,G.C.M.G.; members – Major-General R.B. Hawley, O.B.; Major-General J.H.F. Elkington, O.B.; Director of Clothing – has been appointed to consider this question.

"Professors Abel and Stokes will co-operate with the Committee, and as the utility of the enquiry will depend upon the nature of the questions submitted to these gentlemen, it is recommended that this should be arranged with one or both of them beforehand.

"The Committee will cause experiments to be made as to the visibility of various colours, and the relative merits of – scarlet, green, blue, khakee, and gray (warm or cold shade); and report what colour suitable for military uniform is under all the ordinary conditions of war, the least conspicuous.

"Supposing the colour found to be the least conspicuous is not scarlet, green, or blue, does it possess such advantages over those colours that the Committee would recommend its general adoption.

"It is recommended that the practical experiments necessary to test the various colours had better be carried out at Aldershot.

"C.H. ELLICE, A.G"

The following is the report of the Committee:

"On the termination of the experiments by the scientific members of the Committee and on the rendering of their report, the Committee desire to lay before the Secretary of State the conclusion to which they have come, after careful consideration of that report.

"In accordance with the instructions of his Royal Highness the Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief, at the first meeting of the Committee Professors Abel & Stokes were consulted on the best means of carrying out the scientific inquiry as to the comparative visibility of different colours suitable for military uniform in the field. A detailed account of these experiments will be found in their report, which is submitted herewith.

"It may be briefly stated that a series of experiments were carried out under varying conditions of weather, atmosphere, surroundings, and background – the object being to make them as exhaustive as possible. Various members of the Committee were present during these experiments, which were under the immediate superintendence of Professors Abel and Stokes.

"The result was to eliminate all the colours at present used in the dress of the Army, and the glaring conspicuousness of white and scarlet was at once evident.

"On the other hand, the neutral colours, more particularly the Indian 'Khakee' and certain volunteer grays, were indistinct even at short distances, and, in comparison with the Army colours, all but invisible at long ranges.

"The question was in the end narrowed down to a shade of gray, which, besides its character of invisibility, stands exposure to rain and sun without fading.

"The Committee recommend that this gray (now worn by the 3rd Devon Volunteers) should be adopted as the service dress of the Army.

"As it would, however, be unadvisable to break entirely with the traditions attached to the red uniform of the British Army, the Committee recommend that red or scarlet (and blue or green for corps wearing those colours) should be retained for full dress; but that on all other occasions the gray should take the place of the present undress. By this arrangement the Committee think the advantages, as recruiting, to be gained from an attractive uniform will be retained, while at the same time men and officers will become familiar with a colour which, there can be no question, is the best for active service. The Committee consider that the greatcoats and trousers should be of this gray colour, and that a gray helmet cover should also be issued.

"Intimately connected with the question of the colour of the uniform is that of pipeclayed belts and white haversacks. White, under all but very exceptional circumstances, is the most conspicuous colour of all, and it would avail little to substitute gray for scarlet if the white accoutrements are retained. By the use of an umber colouring (of a similar nature to pipeclay) the belts may be made nearly invisible at a distance, and its employment permits their colour being changed at will.

"This colouring, as prepared by Professor Abel, has been practically tried and found to answer remarkably well. The Committee therefore recommend its general adoption throughout the Army, the umber belts to be worn at all times on active service.

"The haversack, instead of being of white material, should be of the same colour as the belts.

"No practical test was made as to the conspicuousness of the shining metal portions of the soldier's uniform and accoutrements, but it is evident that in sunlight these would attract the eye, and so weaken the advantage gained by the use of gray uniform and brown belts. The Committee therefore recommend that all ornaments, buttons, &c., of the gray uniform should be bronze, and not polished; and that on active service a brown lacquer should be applied to the bayonets, metal scabbards, and all other bright portions of the accoutrements.

"G.J. WOLSELEY, A.G., President

"R.B. HAWLEY, D.A.G.

"JOHN ELKINGTON, D.A.G.

"GEORGE D. RAMSAY, Director of Clothing.

"F.A. Abel.

"G.G.STOKES.

"H.C. REYNOLDS, Major, D.A.Q.M.G., Secretary

"July 25, 1882."

OBSERVATIONS.HC Deb 13 March 1882 vol 267 cc781-5:

§ COLONEL BARNE rose to call attention to the dress of the Army, and said, that, had the Forms of the House permitted, he should have been glad to have moved the following Resolution:— ‘That the present conspicuous colour and tight-fitting Dress of the Army interferes with the efficiency of the soldier and causes the unnecessary loss of many valuable lives.’ He had brought forward the subject last year, when the right hon. Gentleman the Secretary of State for War admitted that a change ought to be made in this respect, and suggested that he should bring the matter on when the Estimates for Soldiers' Clothing were discussed. He regretted that he had not done so; but when the time came two-thirds of the House were absent, and he deferred bringing the subject forward, in the hope that it would receive a more satisfactory discussion than it could have obtained last year. Nothing had yet been done in the matter, and he should like to know whether the right hon. Gentleman really intended carrying out what he had said? He did not complain of want of alteration in the uniform of the Army, because those changes had been frequent, and he knew that some of the small alterations which had been made had been of a vexatious character, and had been the cause of great expense to officers. Last year the right hon. Gentleman ordered the stars to be removed from the collars of the officers to their shoulder straps, and this slight change, which did no good whatever, cost each officer in the Guards about £20. The other day he was talking to an old Militia officer, who told him that since the year 1852 his headdress had been changed no fewer than eight times. His (Colonel Barne's) complaint was that the alterations were made in an entirely wrong direction. First, with regard to the colours worn, it had been found by the Emperor Napoleon that the most conspicuous were white, black, gamboge, and then scarlet; thus, the dress of our Army was composed of the most conspicuous colours that could be found. The Rifles, for instance, who ought to be the least visible, were clothed in black, which was the second most conspicuous colour. Modern warfare consisted largely of battles between two lines of skirmishers, each armed with weapons of precision, so that the loss of life was necessarily conspicuous amongst the more conspicuous body. This was proved by the experience of our men in the conflict with the Boers in South Africa, and more recently by the testimony of the Austrians in Herzegovina. Our losses in the Transvaal War were, generally speaking, due to the superior marksmanship of the Boers, and their ability to pick out our men, whereas the English soldiers complained that they could see nothing of the enemy except their heads. It was found that the grey dress of the Rifles was far less conspicuous. That colour was also advocated by Military and Volunteer officers who had tested the point. He also advocated a change of colour on the ground of economy, for the scarlet dye took the oil out of the wool and impaired its durability. He objected to the tight-fitting tunic, because it did not allow the lungs to expand in a natural way when a man began to ascend a hill, or to do any kind of hard work. The regulation trouser was also objectionable, because it gave an immense drag at the knee, especially if it got wet through. He should like to see the British troops dressed in a Norfolk jacket, breeches loose at the knee, and gaiters, with a light helmet, which would not impede the men in their work. He could not move the Resolution of which he had given Notice; but he had ventured to bring the subject under the notice of the right hon. Gentleman, in the hope that he would consider it, and make a move, if possible, in the direction indicated.

§ LORD ELCHO said, he entirely agreed with the hon. and gallant Member who had just sat down (Colonel Barne), that an unnecessary expenditure had been thrown upon officers by the alteration in the collar and shoulder straps, also that soldiers should wear a dress thoroughly adapted to the work they had to do, and did not think he could add anything to what he had said. As to the question of expense entailed by the changes in the uniform, such as altering the mark of rank from the collar to a shoulder strap, he believed the cost to an officer involved by the renewal of uniform in accordance with the changes was about £20, which he was bound to say was a very unnecessary expenditure. As regarded the question of convenience and comfort in the matter of uniform, he was an advocate of easy clothing, as the movements of a soldier should not be constrained by his uniform. The clothing of the hard-working navvies was loose, and they wore a strap under the knee to prevent the dragging of the trousers. He believed it was a fact that if two men, equal in all other respects, were set to walk, one dressed in knickerbockers or a kilt, and the other in the present uniform of a soldier, in course of the day the former would very considerably outwalk the other; and, besides, trousers were not so fitted for work as other descriptions of clothing. The Secretary of State for War was the person really responsible for the efficiency of the uniform; and he wondered how his right hon. Friend the present Secretary of State for War, who was a most kind and indulgent man, and about as sensible a one as he (Lord Elcho) was acquainted with, when he went down every day to his office could bear to see the sentries with trousers so tight at the knees and baggy below, that it seemed impossible for them to go up and down hill without splitting them. The trousers were, in fact, the very reverse of what they ought to be. It was the custom to ridicule the "peg-tops" worn by the French troops; but they were much more sensible than the trousers of the English soldier. Then, in the Cavalry, the clothes were so tight that the men could hardly mount, and only did so at imminent risk of splitting their trousers. He hoped his right hon. Friend would give his attention to these matters, which were by no means trivial, but essential to the welfare and efficiency of the Army, and would see especially that good and efficient leggings were supplied. He would now turn to the question of colour. As regards the colour, the War Office Volunteer Committee had reported in favour of the Volunteers being clothed in red. He had on his right his hon. and gallant Friend the Member for Berkshire (Sir Robert Loyd Lindsay), who was a Member of that Committee. He was a great advocate of scarlet, and, having won his Victoria Cross in red, naturally thought there was no colour like scarlet for the British soldier. But he (Lord Elcho) did not share in that partiality, and he therefore obtained permission for the regiment he commanded to retain their old grey uniform; and he hoped that, instead of the whole Force being put into red, they would be turned into grey. When the Army went to India, the soldiers were dressed in a uniform khaki or dust colour, and in the Ashantee campaign the dress of the London Scottish was adopted. At the time of the Edinburgh Volunteer Review, he met Sir Frederick Roberts, after he had been round looking at the troops as they were drawn up, and that officer said— ‘I only wish an order would come out that within five years every Volunteer should be clothed in grey instead of red. I am so struck with grey as being a very much better colour than red.’ He (Lord Elcho) had great hopes that, instead of all the Volunteers becoming red, there was some chance from some thing he had heard—and perhaps his right hon. Friend would tell the House if he was right—that the working dress of the Army would be made grey. He was told that experiments were being made at the present with a view of testing what really was the effect of colour at distances in Woolwich marshes and elsewhere. With the small Army we were able to put into the held these were matters of the greatest importance, for it simply meant whether in action a greater or less proportion of our men were to be hit or not. Recently, wishing to try some experiments with a range finder, and sighting a Martini-Henry rifle, he had a target erected at 2,000 yards distance. Had that target been grey, he would not have seen it at the distance; but he covered it with red Turkey twill, and saw it flaming at the other end like a danger signal on a railway. To give them an idea of the accuracy of the weapon, every shot from that distance would have gone into a space not larger than the Palace Yard, or into a regiment in column. Whether they could see men or not at that distance, would depend on the colour of their dress; and with the view of effecting a saving of life, as well as on the score of convenience and comfort, the question of uniform was one which should be thoroughly gone into.

§ MR. CHILDERS said, he was sure no Member of the House would complain of the character of the remarks which the hon. and gallant Gentleman (Colonel Barne) and his noble Friend (Lord Elcho) had made. He must, however, take exception to one of the remarks of the hon. and gallant Member about small alterations of uniform, and especially about the change made above a year ago in the marks on the collar and shoulder strap denoting rank. For these he (Mr. Childers) was not responsible; but he had clearly informed the House last year that henceforward the Secretary of State would be responsible for changes in uniform, and to this declaration he adhered. As to the particular object of the hon. and gallant Gentleman, he quite agreed in his general position that, putting colour aside, the fighting uniform of a soldier should be as appropriate for fighting as the shooting dress of a sportsman or gamekeeper was for the pursuit of game. In one respect the authorities were hardly responsible for undue tightness of dress, which they did not encourage, and which was the result often of commanding officers wanting their men to look smarter, and tightening their tunics. On the question of colour, he proposed to offer some explanation, when they were in Committee, as part of his general statement. He would only say now, that there was more to consider than the mere question of greater or less visibility, important as that was as a factor in the case.