Recently, I read a very interesting book called “Medieval Sword and Shield” by Paul Wagner and Stephen Hand.

The generic title is a little misleading, since specifically the book covers the fighting system shown in I.33.

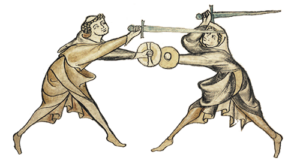

Royal Armouries Ms. I.33, which is the earliest known surviving European fechtbuch (combat manual) and addresses the use of the sword and buckler.

The book “The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship” by Jeffrey L Forgeng has a very nice reproduction and translation of I.33.

The above volumes sit side by side on my bookshelf.

I.33 is not an easy work to understand.

Medieval conventions on artwork make is uncertain as to the actual postures of the fighters, and the text is often less than clear and has some probable errors.

It has been suggested that the manuscript was written for readers already familiar with the system described.

Perhaps there was once an earlier “beginner’s course” manuscript, since lost to history.

If you read I.33, you will appreciate what a sterling job Paul Wagner and Stephen Hand have done in interpreting I.33 into a realistic fighting system.

Their book is comprehensive and logically laid out.

Nearly every technique described is illustrated by a photo sequence, and in most cases the text is on the same page as the photos.

As I know from personal experience, the latter is often much harder to achieve than one might think!

Stab-Knock and Shield-Knock

I.33 only deals with the use of sword and buckler, and the way these are used is distinctive.

The buckler is seldom used independently.

If the sword is held back in a cocked or charged position the buckler is advanced towards the foe.

When the sword is forward, the buckler is kept near the sword hand, and moved so that it is always between the sword hand and the likely approach of the enemy’s blade.

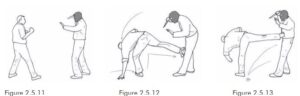

Two of the core techniques of I.33 are “stab-knock/thrust-strike (stichslac)” and “shield-knock (schlitslac)”.

A stab-knock is made when the buckler contacts and controls the opposing blade.

Since the fighter is to keep sword and buckler together, the stab-knock is both an attack and defence in single time.

While the term thrust or stab is used, the attack may actually be a draw-cut or push-cut (aka “file”).

Contrary to the tired old myth that medieval swords were only swung, I.33 shows a number of thrusts.

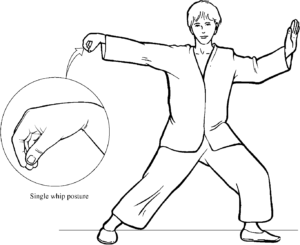

Often the line of the sword obstructs the threat from the foe’s blade. This is reminiscent of the Long Har Chuan variant where an arm punches over an inward parry, simultaneously taking the parry over and striking.

Addressing another common myth: in I.33 a parry or bind with the blade often precedes the involvement of the buckler.

Shield-knock generally refers to binding the foe’s bucker with your own. Ideally. this pins the opponent’s sword and buckler against his body, allowing the fighter’s sword to attack independently.

The latter assumes the enemy has his sword-hand and buckler close together, as recommended by I.33.

Shield-knock is sometimes seen applied to a buckler alone, or sometimes the sword-hand.

If the enemy has not protected the sword-hand with his buckler, then striking his arm with the buckler, preferably edge-on, is suggested.

Shield-knock differs from stab-knock in that the sword may be wielded independently when a shield-knock is used.

Distance, Wards and Counters

I won’t attempt to discuss most of the techniques in Medieval Sword and Shield since they would be hard to understand outside the context provided by the book.

A useful concept that the book describes is that of close distance, wide distance and out of distance.

Close distance is when the fighters can strike each other without moving their feet.

Wide distance is that where a stepping movement is needed to move into striking distance.

Out of distance is where more than one stepping movement would be needed to reach striking range.

Such terminology is fairly common in sword fighting circles but often not so clearly and simply stated in other martial arts.

Another useful concept is the book clearly distinguishes between the terms “ward (custodiis)” and “counter (obsesseo)” as used by I.33.

A ward is a position you adopt before making an attack, while a counter is a position adopted in response to a ward.

It is stressed that one should not “lie” in a ward.

This echoes my own frequent comments about positions and stances not being static and being transitional.

Modern Applications

What can Medieval Sword and Shield teach the modern serviceman or prepper?

More than you might think!

For example, several of the core techniques show elements of Long Har Chuan, and I will deal with that topic further in a moment.

In Crash Combat, I advise the baton and machete user to become familiar with rising and horizontal strikes.

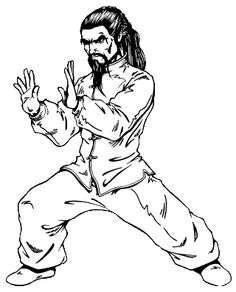

The two most versatile wards of I.33 are “underarm” and “priest’s special longpoint”.

The bucker is held in a similar position for that recommended for the unarmed “alive-hand”.

While we have machetes and other long blades, a buckler is unlikely to be used.

Some of the buckler techniques are not suited to larger shields such as a riot shield.

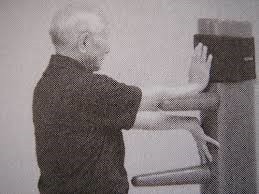

In two of my books I describe using a helmet of entrenching tool in the weak hand to defend from a blade.

The I.33 principle of keeping such a defence between your weapon-hand and the threat is directly applicable.

I.33 shows very few attacks to the hands or arms. The implication is that if the buckler techniques described are used such attacks are highly unlikely.

In combat without bucklers, the hands and forearms will often be targeted, whether a machete, baton or smaller blade is used.

This is why you must keep your hands and yourself moving.

Long Har Chuan and Weapons

As I mentioned already, we can see the core principles of Long Har Chuan being used in some of the fundamental techniques of I.33.

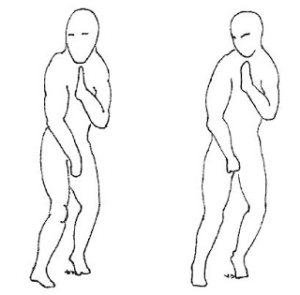

Long Har Chuan boils down to two ideas:

When we make an inward parry, we take over with an outward parry.

When we make an outward parry we simultaneously make an action with our other hand, either a strike or the beginning of another parry.

If we parry a foe’s right hand with an outward parry from our right hand we would move left and hit him with our left hand.

Using a machete or baton has some influence on how Long Har Chuan is applied.

If you have a long weapon in one hand you will likely favour its use.

In offence the weapon has more reach and inflicts more damage.

For defence it has more reach and is less vulnerable than your empty hand.

Suppose your enemy has a machete in his right hand, and you are configured the same.

Your first move will be to bind his blade.

“Bind” has a number of different meanings in blade fighting, and is used here to mean a sustained contact between blades, usually to exert control.

Contact his blade on the outside, with your own, remembering that the strongest part of a blade is near the hilt, so attempt to bind “forte to forte”.

Press his blade to your right and step in to your left. Make contact with his weapon arm with your left hand at the wrist, forearm or inner elbow.

This hand controls, checks and monitors his weapon arm.

This contact frees our weapon hand to unbind and strike at the foe’s neck.

Rather than a broad swing, this may the a thrusting action, resulting in a thrust, draw-cut or push-cut.

If we instead sensed his weapon arm reacting, we might instead strike down at it with our blade.

The procedure is similar for a bind on the inside of his blade, but in this instance his other hand is a potential threat and your should be ready to strike at this if necessary before attacking the neck.

As can be seen, both inward and outward parries/binds are taken over by the free hand to free the blade for use.