Yesterday’s topic logically brings me onto today’s, and another ancient but useful navigation device.

If you have even just glanced through a survival manual, you will most likely have seen the shadow-stick method.

I have previously described this in the context of navigating by the moon. Like the sun, the moon and stars also rise in the east and set in the west.

The method is simple.

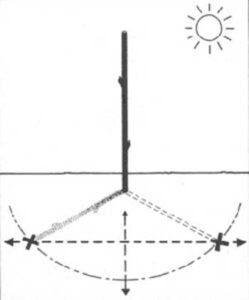

Place a stick or similar in the ground so that it casts a shadow. Mark the end of the shadow.

Wait for at least twenty minutes.

The tip of the shadow will have moved. Mark this new position. The first marker will be west of the second.

Draw a line between the two markers, then run a line perpendicular to this and back towards the base of your stick (gnomon).

This second line will be true north-south. The greater the distance/longer the time between marker placement, the more accurate will be your determination of north-south.

Logically, we will get a more accurate estimate if we take several hours and place a number of markers.

If we do this we will observe that the shadow is longest in the morning and evening, and shortest when the sun is directly overhead.

The arc plotted on the ground will be flattened rather than constant, unlike some illustrations of this method!

When the shadow is at its shortest, it is on the north-south line, and the time will be local midday. The shadow will be shortest at local apparent noon (LAN), which is midway between sun-up and sun-down, so may differ from 1200 hrs.

As well as determining distance, you have also made yourself a crude sundial. This can be useful in determining true local time.

Some countries on the same longitude use different times. China spans several time zones but uses one official time for the whole country!

The principle is simple enough, but it can get confusing which end of the north-south line is north. In the northern hemisphere the sun (or moon) rises in the east and travels west, passing through the south. In the southern hemisphere it goes through the north.

- In the northern hemisphere the shadow always points in a northerly direction. At midday the shadow will point due north.

- In the southern hemisphere the shadow always points in a southerly direction. At midday the shadow will point due south.

Memorize that and solar navigation becomes much less confusing.

In the movies, air-crash survivors usually undertake an epic journey back to safety.

In the real world, your prudent strategy is to stay near the crash site if practical.

Setting up a shadow stick is a practical way to spend the time, and establishing the bearings of visible landmarks may be useful later on.

Suppose, for whatever reason, you need to travel. This decision should never be made lightly.

Thanks to your shadow-stick, you know what bearing you are heading out on, and that of some of the local features.

But we cannot take our compass/sundial with us!

With a few modifications, we can make a portable variant.

If you have ever read about the early days of the SAS or of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), you will most probably have encountered to references to sun-compasses on their vehicles.

In those days, trying to use a magnetic compass while riding in a large lump of steel was problematic. The solution was the sun-compass.

Descriptions of how the sun-compass was used used to be hard to find. Thankfully, this is changing.

The sun-compass is an ancient device, and was used by the Vikings, among others. A version was also used by some Apollo missions on the moon.

As you can see, some sun-compasses are very complicated or sophisticated, so not really something you can improvise.

I am going to describe a less accurate variant that can be easily constructed.

In the previous blog, I described how a circle of 57 mm radius had a circumference of c.360 mm. (The person who taught me this trick had 5 mm and 57 mm marked on the zipper of her jacket. I notched my penknife handle).

Create such a circle on a piece of paper, back of a notebook, etc.

An alternate name for a sun-compass is “shadow board”, which reminds us it can be made with a piece of plank or other flat material.

A folded piece of paper will help us mark off the 45, 90 and even 22.5 degree points.

Each 1.5 cm of the circumference is 15 degrees.

The radius of a circle can be measured twelve times along its edge using a drawing compass, or an improvisation of one.

By folding the marked points together the circle can be divided further into 24 parts, or the drawing compass can be used further.

A nail or pin can be used as the gnomon, but a sliver of wood is more likely. In fact, you do not have to mount the gnomon, just place a shadow-casting object in the centre of the circle whenever you take a reading.

All we have to do now is mark off the circle. This will be a 24 hour clockface so mark off every 15 degrees with an hour.

Remember that the shadow will point due north at midday in the northern hemisphere, so mark 1200 hrs as North/0 degrees (In the south, 1200 will be South/180).

Fill in the rest of the face. You might get something that looks like this:

Using this simple sun-compass is simple.

Hold it level and rotate it until the gnomon shadow is over the current time. If the clocks are adjusted for daylight saving/BST or similar you will have to account for this.

Remember, “spring forward, fall back”, so the shadow will be on the north-south line at 1300hs, not 1200, so you will have to subtract an hour from local time to get the time to read on the dial.

Once you have your sun-compass orientated, use the dial to find the bearing you want. Your portable sun-compass should agree with your base-camp shadow stick.

Pick out a landmark, put away your sun-compass and walk towards the landmark.

An alternate method is to do the same as you did with a shadow-stick. Erect a little gnomon on a board or sheet of paper and plot the tip of the shadow over the course of a day.

Draw a line from the base of the gnomon across the curve where it is at its closest.

To use this version you do not need to know the time.

Rotate the sun-compass until the tip of the shadow meets the curve. The line you drew will point north (or south if you made your sun-compass in the southern hemisphere).

You must use the same height gnomon for each reading, so mount this permanently.

The Ottomani version is suspended from three or four points by cord to ensure that it is level.

You may have realized that if you know the bearing of something, your sun-compass can be used as a crude sundial.

Related to the methods described above is using a watch directly to navigate by the sun.

Remember to adjust time for BST/DST. Substitute “1 mark” for “12 mark” in the above instructions.

If your watch is digital, or you are using your phone clock, use your imagination.

If you become confused as to which end of the north-south (N-S) line is north, check the local shadows.

Hold a blade of grass over the watch-face and see if it casts a shadow. The one direction a shadow cannot point in the north is south.

Useful to recall is “the north gets up around 3 o'clock, goes to bed around 9”.

In other words, the north end of the N-S line will be in the small numbers in the morning, the higher numbers in the afternoon. (In the southern hemisphere replace the word north with south and the motto still works.)

Remember, sometimes shadows are still visible even when you cannot see the sun directly.

The basic watch method is easy to remember: midpoint between “12(/1)” and the hour hand.

The specifics for each hemisphere can be difficult to remember.

It may help to think that “N” for north-hemisphere looks like a “H” for “hour-hand” and that this should be pointed at the sun. A cast shadow will point in the opposite direction to the hour hand.

For the southern-hemisphere, the 2 in “12” looks a little like an “S” so the 12 should be pointed at the sun. A cast shadow should point towards “6”.

Hopefully that will help you use this method.