My recent article on the simplicity of the Soviet soldier’s kit made me think about some of the items that are not included in the equipment list.

Specifically, I thought about fire kits.

An idle moment on the internet turned up commercial fire kits with nearly a dozen different types of tinder. They also came with a big price tag!

We all know fire is important for survival, but what do you actually need in your fire kit?

One of the most useful items you can carry are disposable lighters.

Zippo lighters are touted as “the professional’s choice” but in my experience they seem to need frequent refilling.

Interestingly, “Detachment B-52 (Project Delta) Reconnaissance Tips of the Trade” has the advice: “Do not take cigarette lighters as they make too much noise when opening and closing.” This is clearly in reference to zippo-type lighters.

For the same price as a Zippo, you can have dozens of disposable lighters that keep their fuel until it is used.

Take a look around your local pound store and you’ll see them being sold in multiple packs. Invest in a few of these.

Bright colours reduce the chance of losing them in the woods.

Place at least one lighter in each emergency kit that you have.

Put one in each outdoor coat that you own.

Throw a couple in the glove compartment of your car.

A disposable lighter will give your many more ignitions than the equivalent weight of matches. Some disposable-type lighters may be refilled.

Optional: wrap the outside of your lighter with a few inches of duct-tape. Duct-tape is flammable and a small piece may be lit with the lighter and used to get a fire going. It may be used like a candle, as described later. The duct tape is also handy for repairs and other duties.

The only real objection to disposable lighters is that there can be a fairly broad quality margin. Some disposable lighters seem to last for ages, others do not.

Allow for this by having a pair in your main fire kit.

A butane lighter that has run out of fuel can still provide a useful spark, and can be operated one-handed, unlike a traditional flint and steel. For this reason, the disposable lighters that have a striking wheel are preferable to other ignition systems.

Even when the lighter “flint” is exhaused, the wheel may still be used to strike sparks from a ferro-rod. This saves your knife blade, and is handy if your knife blade is of a steel that does not readily throw sparks..

Twice I have managed to run a butane lighter through the washing machine.

The first lighter changed colour from green to turquoise, but continues to work fine.

The second, a flint and wheel type, I found on the floor while unloading the laundry. I picked it up and tried it, and it lit immediately!

Disposable lighters seem to be more tolerant of water than you might think!

I have come across claims that butane gas lighters will leak in low pressure environments. This may or may not be an actual problem if you are a mountaineer. For the rest of us, lighters are a very practical source of fire.

Butane lighters may be difficult to light when the temperature drops to zero or below. In such situations, carry at least one in your trouser hip pocket or an inner pocket where your body heat will keep it warm.

The second thing your fire kit should contain is tinder and something to carry tinder in. Ideally your tinder container should be waterproof.

A 35mm film container is close to ideal. Ideally the lid should be attached to the container body so it cannot be lost. A strip of cord or plastic and some superglue solves this.

While film containers are not as common (or cheap) as they once were, they can still be found from on-line sources. They are sometimes marketed as “geocache” containers.

While researching this I was stunned by a site asking £123 for 15 35mm containers!

Alternate Containers: One reader of this blog informs me he can scrounge pill bottles from local pharmacies. Another suggests that the little tins that the glucose test strips for diabetics come in can be used.

I have access to 50 ml screw-capped centrifuge tubes but to my mind these are a little too big.

At least one brand of storm matches comes with a container that might be suitable. Buying the container alone is nearly twice the cost of buying it filled with storm matches! Not sure if the cheaper examples have a screw-thread cap, however.

Pack your container with cotton wool.

Melt some Vaseline in an old spoon over a gentle heat. You will probably find Vaseline in the same store you brought the cotton wool from.

Pour the Vaseline on the cotton wool.

Pack that down, put fresh cotton wool on top and melt more Vaseline.

Keep repeating until your container is full of Vaseline-impregnated cotton wool.

Cotton wool is an excellent tinder. The Vaseline helps repel water and extends the burning time. You will only need a little, which can be teased out before ignition.

Wrap a little piece of Vaselined cotton wool around a stick before igniting, and then use this like a match/candle. You may also split the end of a stick to hold the cotton wool, or handle it with twig “chopsticks”.

As you use up the Vaselined cotton wool, you replace it in the container with “found tinder”.

“Found tinder” is anything that you find in the field that can be used as tinder.

It includes thistle or dandelion down, clothing fibres, scrap paper, woodworm dust, sawdust, shredded spent matchsticks, bird down, belly button fluff and many other materials.

Some outdoorsmen prefer to have a second container for found tinder.

You want to keep your found tinder dry. Dry it near a campfire or in the sunlight when opportunity presents itself.

Candles are a useful addition to a fire kit.

A small bundle of birthday cake candles is nicely compact.

Whenever you strike a match, use it to light a candle. If your fire won’t light with the first attempt with a lighter, use the lighter to light a candle, and use the candle for a sustained source of ignition.

If your tinder will not light after five seconds of exposure to a lighter flame, try something else.

Candles therefore conserve your supplies of matches or lighter fuel.

The final item I would include in the fire kit is a magnifying lens.

This can be used for fire-starting on sunny days. “The only fire-starter on Earth that isn’t!”

Your compass probably has a magnifying lens on its baseplate but it is worth including an additional one in the fire kit.

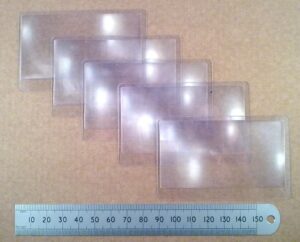

I recently picked up five Fresnel lenses for £1.99, less than the price some companies charge for one, so shop around.

I confess I have not started any fires with these yet since as soon as they arrived the sun disappeared!

The suggestions below is a fairly basic but capable fire kit:

•A pair of lighters.

• One or two tinder containers.

• Vaseline-soaked cotton wool.

• Bundle of birthday candles.

• Fresnel lens.

Store in a sealable waterproof plastic bag. Double-bagging is a good precaution.

Some of you will note that this kit does not contain some of the more traditional survival fire-starting items.

There are no matches or storm matches because I believe the lighters are more space efficient. A single disposable lighter is estimated to be equivalent to a hundred books of matches, so it is obvious which is preferable. If you have matches, however, by all means use them!

Conventional matches may be made more water-resistant by pouring molten candle wax over them. You may dip them individually but it is easier create a block of wax with the matches encased. The alternative idea of painting the matchheads in clear nail varnish may also be encountered, but will be more time consuming than the wax method. You will need to scrape the wax or varnish from the head before attempting to light them.

Matches may be packed into any wide-mouthed, suitably sized plastic bottle, so long as it is watertight. Do not forget to include the striking surface!

There is no ferro-rod and steel in this kit because the lighters can do the same job and are more effective.

Lighting fires with a ferro-rod is fun, and you should know how to do it. But when things get serious, have a couple of lighters handy.

If you already have a ferro-rod, carry it.

I have a waterproof match container that came with a ferro-rod glued to the side. Unfortunately the container is a little too narrow to make a good tinder carrier.

If you do not have a ferro-rod and striker, invest in some lighters and the other items first.

Shop around for a ferro-rod and steel if you want one. Prices vary considerably and some will cost you the same as a score of lighters!

seen it suggested to use a spare pair of trousers. Tuck one leg into the other to form a double layer and then tie a knot in end of the leg(s).

seen it suggested to use a spare pair of trousers. Tuck one leg into the other to form a double layer and then tie a knot in end of the leg(s).  A variation of the above is the wick method. Fill a container with your crude, suspect water and place an empty container lower down. Connect the two with a strip of cloth such as a bandanna and allow capillary action to do its thing. This may work with other materials such as paper or string. Experiment.

A variation of the above is the wick method. Fill a container with your crude, suspect water and place an empty container lower down. Connect the two with a strip of cloth such as a bandanna and allow capillary action to do its thing. This may work with other materials such as paper or string. Experiment.  Bow length varied with tribe, intended use and probably the individual. Bows of six foot or longer were known, as were bows of only a few feet. A suggested measure for a bow was the distance from the left hip to the right hand when the hand was held out horizontally to the side. This is about four feet. Some readers will recognize this as

Bow length varied with tribe, intended use and probably the individual. Bows of six foot or longer were known, as were bows of only a few feet. A suggested measure for a bow was the distance from the left hip to the right hand when the hand was held out horizontally to the side. This is about four feet. Some readers will recognize this as