About a week ago, I posted the second part of “Knives You Need”, discussing Swiss Army Knives.

Since the first version went up, I have added more links and more content.

The pocket clip for my Swiss Army Ranger arrived, so I have posted an additional image of the new scales with the clip installed.

I have also put a few additional modifications on the page.

For today’s chapter of Survival Library, it seems appropriate that I look at two books that look specifically at the use of Swiss Army Knives.

Whittling in the Wild

If you are interested in Swiss Army Knives, you will have encountered videos posted by Felix Immler. Most of the links from my previous blog are to videos by Herr Immler, and for good reason.

There is a lot of rubbish on Youtube, but people like Felix Immler are a welcome breath of fresh air!

Immler has written several books on the Swiss Army Knife, but I have only been able to find a copy of “Whittling in the Wild”. It may be found under variations of this title such as “Victorinox Swiss Army Knife Whittling in the Wild”.

Felix Immler has apparently done a lot of work encouraging young people to experience whittling and create objects for themselves.

Most of the projects in this book are toys, fun‑stuff or curios. This is not the book to teach shelter construction or how to make a better rabbit trap. However, within these projects are many construction techniques that might be put to other uses, so they are worth a browse.

The book is worth reading just for the sections on safely using your Swiss Army Knife and basic handling techniques.

If you have young people you want to teach to use a knife safely and creatively, this is an ideal book. Many of us longer in the tooth and barer in the pate may learn a thing or two too!

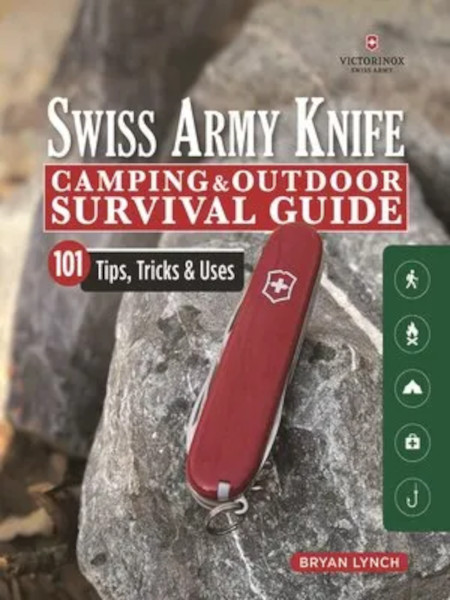

Swiss Army Knife Camping & Outdoor Survival Guide

The second book is “Swiss Army Knife Camping & Outdoor Survival Guide, 101 Tips, Tricks & Uses” by Bryan Lynch.

Part One of the book mainly looks at a variety of knife models from Victorinox, ranging from the 58mm Midnight Manager to the SwissChamps and several of the locking blade models.There is a nice chart comparing the models included in the book.

To my mind, this selection misses out some of the more humble, but more useful variants such as the Climber, Compact, Huntsman and Ranger.

Part Two is a nice section on safely using and maintaining your knife, including sharpening tools such as the wood saw and the chisel.

Part Three is on using your Swiss Army Knife in the wilds.

One oddity of this section is the author states that the distance of an arm‑span, fingertips to fingertips, is “roughly 5 feet (152cm)”.

Generally, the arm‑span is taken to approximate an individual’s height. For me this is bang‑on: distance from the centre of my chest to finger tips is exactly half my height.

The author later mentions that he is “a little on the short side”. The quick measuring scale he illustrates will not apply to the majority of readers. As he himself states “Obviously everybody is different, so premeasure your own limbs”.

Most of this part are presented as “projects” with an estimated time. Most of the projects are survival ideas that will be familiar from other sources.

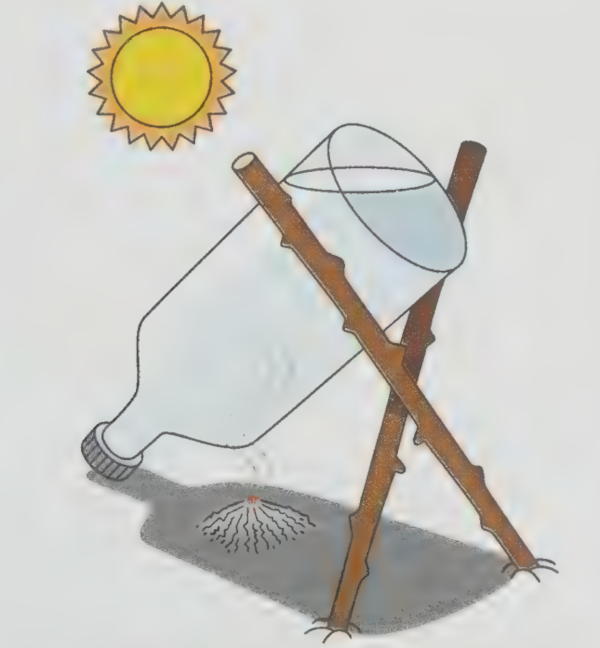

Many are nicely described, and include the occasional less‑well known idea, such as the fire‑plow. Wilder has a nice story about someone using a fire‑plow, but I have seldom seen mention of this device in other publications, although it is included in some versions of FM 21-76/3.05.70 and the SAS Survival Handbook.

There is a suggestion about carrying wire wool under the corkscrew. I wonder if contact with the corkscrew will encourage the wire wool to rust, which makes it even less useful for firelighting. It is not a particularly good tinder for non‑electric sources of ignition. Some Swiss Army Knives have an LED. Can steel wool be ignited with the batteries for these?

There are far more useful things to carry than steel wool.

When using the back of the saw or some other tool with a ferro‑rod, it is more effective to draw back the ferro‑rod while placing the “steel” on the tinder.

I liked the section on carving wooden fish hooks from branched twigs.

The author talks about “catch and release” sport fishing.

Some mention might have been made that the paracord net described (or any net made with knots) will damage fish and should only be used for emergency or sustenance fishing. Similarly, wooden gorges as hooks are very cruel, often illegal, and should only be used in genuine emergencies.

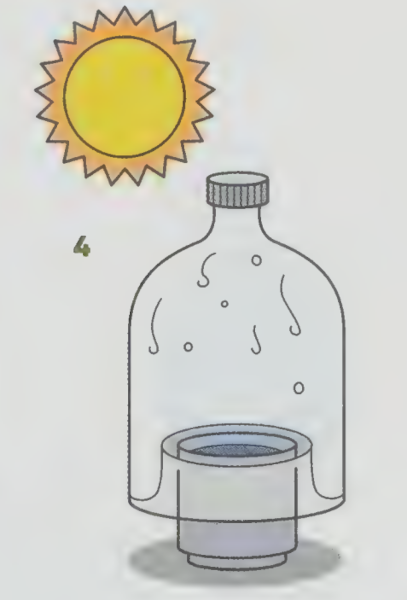

While fish trapping with a bottle is mentioned, there is no mention of trot‑lines, which are likely to be more efficient than active fishing in an emergency.

There is a useful section on how a Swiss Army Knife may be useful for firearm maintenance and cleaning.

I also liked the tip on making a squirt bottle for cleaning out wounds. Yet another use for the sometimes maligned reamer! A bottle with a drinking nipple can probably be used the same way.

“There is a lot of wasted space in a vehicle, and I urge people to use it.” Good advice, although I would stress having something like a rain poncho, duct tape, vehicle tools and a sleeping bag or poncho‑liner.

Imagine attempting to repair your vehicle in very bad weather. It will help to have a means to keep the rain or snow off what you are working on.

In the “Urban” section, the author describes getting locked in a washroom cubicle. Similar happened to me in the toilets of a very famous museum. Like the author, I used my Swiss Army Knife to dismantle the lock and free myself.

Summary

In summary, I liked both of these books. Each is worth a read. I was lucky in that I was able to read both of them together.

There is a good possibility that when you really need a tool, your EDC Swiss Army Knife may be the only tool available. These books provide a nice reminder that you are better equipped than you might fear.