In a recent blog, I had a wander into the field of fighting knives.

Today I would like to share some additional musings.

Firstly, it is valuable to recognize that names such as “fighting knife”, “combat knife” or “tactical knife” are in actuality rather euphemistic, particularly in modern applications.

A knife vs knife duel is unlikely.

There is an adage that if you find yourself in a fair fight, you did not plan properly, and this should be remembered when considering knife use.

Knives are generally used either as weapons of desperation or advantage.

One of the points I made in the previous post is that probability of use did not justify carrying a large combat design.

A multi-role survival blade is a far better encumbrance, and most such designs usually serve well in a defensive or offensive role.

It is no secret that I regard the kukri as superior to most fighting knives on the market.

If a dedicated fighting weapon is needed, it should be a small to medium-sized design that compliments the large and small survival designs likely to be carried as well.

That said, what are useful features to have in the hypothetical situation where carrying a large combat blade is prudent? Something for you time-travellers and trans-dimensional trippers to consider 🙂 Some of these comments may be relevant to medium combat knives too.

The "Military Art of Training", published in 1622, advocates very strongly the wearing of the dagger by soldiers, and it quotes six reasons in support of the case:

(1) The handsome appearance of the weapon;

(2) Its advantage over the sword at close quarters;

(3) Its superiority in a private combat;

(4) Its utility for the speedy despatch of the vanquished;

(5) Its advantage as a means for tethering a horse in the open;

(6) Its awe-inspiring effect if drawn by an officer when sedition is imminent.

Firstly, we will ignore the field of swords, and stick to knives and daggers, not anything longer than a cubit.

A point ignored by many manuals on knife use is that even relatively light clothing can provide a surprising amount of protection from a knife cut. The garment may be shredded. but very little damage may reach beneath the skin.

Even if you are using a knife defensively with the intention of “cutting and running” it is important to use the point first against any clothed area.

Pesh Kabz

The second consideration for a fighting knife is with respect to whether the opposition will be utilizing armour.

One of the most useful designs for use against armour is that of the pesh kabz.

Mechanically a knife is a wedge. The pesh kabz blade tapers in both width and thickness, and has a T-shaped cross section. In effect the blade is an isosceles triangle in all three planes.

The blade is narrow enough to find its way through openings in the armour, yet retains a useful cutting edge if needed.

Some time back there was a vogue for non-metallic knives, including those in a tanto configuration.

A pesh kabz configuration would have been far superior.

As stated in “A Glossary Of the Construction, Decoration and Use Of Arms and Armor In All Countries and In All Times” by George Cameron Stone, “The knife is obviously intended for forcing an opening in mail; and as a piece of engineering design could hardly be improved upon for the purpose.” (p.494)

Pesh kabz are either straight, or have a recurve that brings the point closer to the axis of the hand. The latter are often very attractive in form.

I have an example of each, and I would not complain if issued one of these instead of a Fairbairn-Sykes. A modern pesh kabz has a useful potential as a knife among modern medium fighting knives.

Bagwell and Bowies

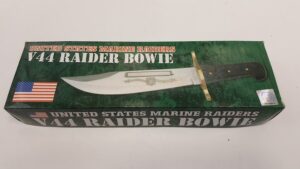

Shortly after writing the recent blog, I came across some references to Bill Bagwell, who claimed to have identified the features that were most desirable on a combat bowie.

This list of features included a distal taper, convex profile and edge and a sharpened false edge. The false edge is often quite long, creating an acute point. The blade is over nine-inches long, and over an inch or more wide.

Pugio

If you are going to have a long, sharpened false edge, an obvious question is why not have a double-edged cut and thrust blade?

Historically, one of the cut and thrust weapons par excellence was the Roman gladius. The gladius was a sword, but if you shorten the blade you have what is effectively the Roman pugio.

I have seen it claimed that a Roman soldier who lost his gladius could still fight effectively with his pugio. The width and length of pugiones give some credibility to this claim.

Pugiones seem to have retained the more attractive, wasp-waisted leaf-shape of blade long after the gladius had become straighter-edged and more utilitarian looking.

This may have been that swords were issued while daggers were commonly a private purchase.

In other words, a pugio-type design offers a broad blade, acute point and the cutting advantage of curved edges.

A central rib was a common feature, increasing the capability against bone or body armour.

A flat blade with a rib is effectively a pair of pesh kabz back-to-back.

Fullers might also be included in a modern design, and some use of them was made in ancient pugiones.

Jambiya

Another good design for a large or medium combat knife is the jambiya.

Indian/Middle Eastern designs such as the jambiya and pesh kabz tend to be neglected in the west, but have much to offer.

The interest in kerambits/ karambits shows knife-users are open to the potential of curved blade designs.

Fairbairn himself experimented after the war with a jambiya-like knife he called the “cobra”.

Like the pugio, the design of a large tactical jambiya could include fullers and a central rib.

A slightly curved blade can create an initially wider wound than a straight blade of similar dimensions. This is illustrated in the figures taken from Richard Burton’s “Book of the Sword”.

The very curved blade cuts a wide channel, but needs considerable force to penetrate sufficiently.

Incidentally, the primary cutting edge of a jambiya is the concave edge. You will commonly see it held or photographed upside down.

Examples with a false edge, and the geometry of some grips make it clear that the main edge is the concave.

The jambiya is held like a claw or hook. This has the tendency to drive the point into a target rather than causing it to glance off. The blade can also reach over and hook limbs. The curved edges give a cutting advantage.

The Russian/Caucasian/Georgian khanjali/kindjals/qama have straight or curved blades that resemble gladius, pugiones and jambiya, but some are long enough to be considered short swords.

Some decades ago, a knife called the “Hobbit” gained some attention.

The Hobbit was effectively an inverted jambiya.

The main edge should have been concave and the serrations would have been more useful on the convex side.

A modern, medium tactical jambiya would also be a welcome addition to the market.

Many years ago I attempted to sketch what one might look like

Length

Around 1922-24, the British Army conducted an extensive series of experiments.

The 17" sword bayonets then in use had proved to be unwieldy and too heavy for trench warfare. Their reach against cavalry was no longer needed and they were poor multi-purpose implements.

On October 2nd, 1924, a report by the Small Arms School stated:

“ (a) It has been conclusively proved during the war, and since, with our present system of training in the bayonet, that ‘reach’ is not a main factor but that ‘handiness’ is. A man with a short handy weapon will beat an equally skilled man with a longer cumbrous weapon practically every time. As regards length of blade for killing purposes, the Physical Training Staff went into this in considerable detail during the war, and came to the conclusion that a 6-in. blade was sufficiently long to deal with the most thickly clad of our enemies—potential or otherwise. The most thickly clad was taken as being a Russian in winter clothing.

…(c) The bayonet suggested for future adoption on the Mark VI rifle is one of about 8 inches in length, cruciform in section, and without the useless handle and cross-piece”

reproduced in The Lee-Enfield Rifle (p.135). Maj. E.G.B. Reynolds.

The Roman Vegetius famously declared “…a stab, though it penetrates but two inches, is generally fatal”.

He was talking of a stab from a broad gladius blade, rather than a narrow bayonet or knife, however.

Many authors clarify “two inches, in the right place”, the latter condition not always possible to achieve in combat!

Some of the criteria for a primary fighting knife are different to those for a bayonet.

A blade of between nine and eleven inches seems to be the optimum, and was the size of most pugiones.

The blade should be at least one and a half inches at its widest.

Specialist fighting designs, such as main gauche, may need to be longer.

Grips

If we look at pugiones, kindjals and jambiya we find something of a consensus on grip form.

Most examples feature a relatively slim grip with a broad, flattened butt.

A narrow grip between two wider areas often gives a good grip for a single hand.

If you hold the knife or sword with the blade flat and level and the knuckles upwards you will find the pressure of the palm on the butt nicely counterbalances the weight of the blade.

The pugio usually had an expanded section in the middle of the hilt which improved grip, functionally similar to the ridge on a kukri handle.

Any grip should include provision for a wrist loop. It is surprising how many knives costing hundreds of dollars lack this useful feature!

On the subject of grip, how a knife is gripped is a topic that some authors treat in some depth. Fencer grip, hammer grip, sabre grip, ice-pick grip, foil grip, ninja grip and so on.

Only recently, I noticed that the actual orientation of the hand was seldom mentioned.

Elsewhere I have discussed the “paintbrush grip” for double-edged blades. This tends to place the blade with the flat of the blade in a horizontal direction.

When I hold a single-edged knife I place the blade in a similar orientation, although my finger positions will be slightly different.

The reason for holding the knife so is not so the blade will slip between the ribs. Whenever possible, you should avoid thrusting at the ribcage.

If you do have to strike the ribs there are advantages to a horizontal blade angle, however.

I have seen it claimed that a horizontal blade that strikes a rib is more likely to glance past or split the rib than be stopped by it.

The main reason I hold a blade horizontal is that it makes more sense to me to have the edge as well as the point directed towards the threat.

If my hand is pronated (palm down) the blade slopes in. If palm up, it slopes outward. In either case, the main edge is towards the enemy rather than down towards the floor.

Some older sources describe holding the blade edge up, but this limits manoeuvrability.

Guards

The guard of the fighting knife is something that is not usually given sufficient thought.

If the knife has a guard, it is typically a simple crossbar or equivalent.

A simple crossbar works well on a sword. It will usually be wide enough to protect the hand. Enemy blades seldom touch the guard since a sword is long enough to parry attacks a foot or more away from the hand.

Some writers claim the main function of a sword guard was originally to stop the user from hitting his knuckles on an enemy shield.

The crossbar on a knife is seldom wide enough to effectively protect the hand. At best, it acts as an arrest to reduce the chance of penetration beyond the blade and to compress tissue for deeper penetration.

Even when the crossbar is long enough, it only provides protection in one plane.

Suppose, for example, you parry or block an attack with your blade. Since the blade is shorter, the contact point is going to be much closer to your hand than if you were using a sword.

Contact point is most likely to be on the flat of the blade, so the strike is very likely to glance down and hit your thumb or back of your hand. Potentially very nasty

In a Modesty Blaise novel, a character observes that Willie Gavin makes a steel against steel block, and reflects on Gavin’s skill, knowing that this is the most difficult of defensive movies with the knife.

Substitute “bloody dangerous” for “difficult”!

Certain styles of knife-fighting base themselves on sword fighting, so techniques involving parrying may be encountered.

One of the lessons here is to avoid using your knife (or your other hand) to parry, if possible.

Avoid letting your enemy make any contact with your weapon or hand.

If you do make contact, execute a “beat” and strike to the hand and arm beyond.

Keep both hands moving, and keep moving yourself.

Use your ginga and the other techniques in my books to avoid and attack rather than parry and block.

As an aside, the above implies there must be some length of blade over which parrying becomes practical.

Drexel-Biddle taught parrying, but had his students were training with hand-held sword-bayonets.

I would be fairly confident parrying with a ten-inch kukri. Shape and design probably contributes too. The forward curve of a kukri or jambiya increases control and compensates for length.

All that said, if I am designing a primary fighting knife, I would include a guard. Down-curved quillons that can catch a blade would be nice, although how realistic this is is debatable, and such a feature certainly needs to be backed by protection for the hand behind.

An oval or ovaloid guard, such as found on a tanto, might be a good option. The tanto, hamadashi, aikuchi and related designs themselves are good options in addition to the designs already mentioned.

As I understand it, “tanto” actually means (very) short-sword and it is not technically a “to” or sword unless it has a to-type guard and other sword fittings (Cameron Stone, p.604).

Most modern knives sold as tantos would not be classed as such, and the wikipedia article is erroneous [!]

A guard that provides protection in two planes may be problematic to wear.

One option is to offset the disc so less of it is against the body but it still protects the outside of the hand.

Renaissance daggers often combined quillons with a “thumb ring”, the latter a misnomer since it was positioned to defend the outside of the hand rather than involve the thumb.