Recently, I have been watching the “Rurouni Kenshin” series of movies. “Origins” was a little slow and melodramatic, but the main ones are great entertainment.

The lead character's gimmick is they use a sword with a sharpened back‑edge and a blunt main edge. He clubs enemies down with the main edge in an attempt to not take any more lives.

This reminded me of a passage in Don Cunningham's book “Taiho‑Jutsu”:

“For such situations, the machi-kata dōshin [samurai police official] carried a special long jutte, usually with a tapered six- or eight-sided shaft, as their primary weapon and arresting tool. They also only wore one short sword in their obi. The dōshin either grinded the ha (sharpened edge) off their wakizashi or carried special wakizashi forged with extra-thick dull blades. The short blunted wakizashi were considered more suitable for making arrests, especially within confined spaces. A resisting suspect could easily be stunned and immobilized with a strike from such a blade without risking a potentially lethal injury as with a sharpened sword.”

I will admit to being sceptical as to whether anyone ever ground the edge off a perfectly good and valuable wakizashi for such purposes. It seems easier and more effective to fit a suitable strip or billet of iron with sword furnishings.

That such blunted weapons were carried seems possible, since the feudal police seemed to have taken considerable lengths to take their suspect alive.

Why did the police officer have a blunted sword when he already had a jutte? Possibly to show that he had samurai rank. Why did he carry a wakizashi rather than a daishō? The following passages should shed some light on that.

Most readers will know that the samurai wore two swords, known as a “daishō”. It would become enshirned in law that a samurai on official business was required to wear two swords.

Daishō means “big and little” and reflects that the two swords were of differing lengths.

In earlier periods, the daishō might be a tachi and a long tanto. By the Edo period, both weapons were katana, which were worn edge up.

In modern usage “katana” is a term usually used to distinguish the long sword. Historically, the term could be used for either of the daishō, and to distinguish them the terms “uchi‑katana/uchigatana” were used for the longer sword (“daitō”) and “chisa‑katana/chisagatana”, ko‑dachi, kogusoku, ko‑katana, wakizashi or shotō for the shorter.

To avoid confusion, I will reserve the term katana for the longer sword, as is common modern practice.

Why Did The Samurai Carry Two Swords?

Part of the reason was probably symbolic. Two swords was the symbol of a samurai and if you were a samurai, you therefore wore two swords.

Practical explanations for the practice are less satisfying. The short sword was a backup for it the long sword was lost in battle. The short sword was for removing the heads of slain opponents. The short sword was for seppuku.

Other than length, the short and long swords are effectively the same in design. Why a short sword would be better at cutting heads from corpses than a longer variant flies in the face of basic physics. Taking heads was also a task attributed to the kubikiri/kubigiri, which is of a very different form to either of the daishō.

Was the wakizashi carried for seppuku? Most samurai movies seem to use the katana with a cloth or paper wrapped around the blade for grip.

George Cameron Stone's book, “A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times: Together with Some Closely Related Subjects” (p.658) claims the wakizashi was used for seppuku, but its use had declined in favour of a dagger in more recent periods.

Some samurai fought with a blade in each hand, and utilized their wakizashi in their left. This seems to have been an uncommon practice, however.

Some writers have dismissed the wakizashi as redundant and superfluous. And yet, the wakizashi or weapons like it were widely carried for at least six hundred years!

Safety in the Home

The samurai did not always wear both swords. Etiquette required the long sword not be worn indoors when visiting a superior or another samurai. Wearing the long sword in such a situation was disrespectful, if not outright suspicious and threatening.

In his own home, the long sword might be stored in a rack, or entrusted to a servant for cleaning and sharpening.

When indoors, the samurai only wore his wakizashi, or possibly just a tanto. If the wakizashi was not worn thrust through his sash, it would be within easy reach, such as beside him as he knelt on the floor.

If a samurai was attacked in his home, the wakizashi or tanto would be the weapon most likely to be available.

The wakizash/tanto were the weapons the samurai would have to rely on when he was in most need of a defensive weapon. Not surprisingly, there was a considerable body of training on how to use a wakizashi.

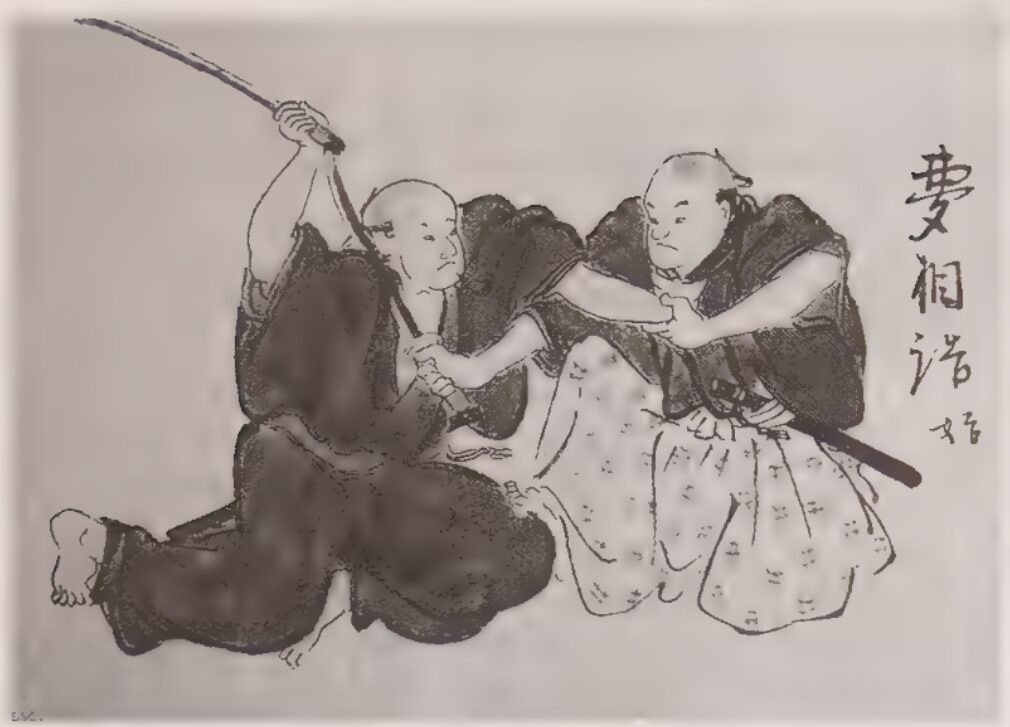

Indoor combat might be at close ranges, so the use of the wakizashi and other weapons was studied in conjunction with grappling techniques. Techniques that could be used while kneeling or seated were also studied. Some techniques involved hindering an attacker drawing their weapon, or taking their weapon and/or using it against them.

For example, as a kneeling attacker attempts to draw a wakizashi, a hand on his wrist may prevent him completing the action. The wrist hold and the other hand are used to unbalance and throw the attacker forward, possibly falling on the exposed edge of his own blade.

If he could afford it, a samurai would see that both swords of a daishō would have matching fittings and decoration. Ideally both were made by the same craftsmen. Stone suggests that the wakizashi would often be the more ornately decorated, since this is the sword that would be worn during indoor social occasions.

The wakizashi was also the one of the pair likely to mount accessories and implements such as the kogai and kozuka. This made these items available when the long sword was not being worn. This approach may have also prevented the possibility of the kogai and kozuka interfering with the draw of the long sword. Kogai and kozuka were sometimes used as expedient bo-shuriken, so having them with the wakizashi might have given the wearer another option if attacked indoors.

Something for the Ladies

Samurai women were expected to fight in defence of their homes and persons. The naginata was the usual weapon of choice, but instruction was given in the use of the wakizashi and dagger and include the kusarigama.

The naginata and kusarigama are relatively long‑ranged weapons. If an enemy got too close, or combat was indoors, the wakizashi or dagger were a useful alternative.

For Lord and Commoner

Only the samurai were permitted to wear the daishō. In addition, commoners (non‑samurai) were not allowed to have long swords.

What is not so commonly know is that commoners were permitted to have short swords.

Cunningham notes (p.22):

“While katana (long swords) were prohibited, chōnin [townspeople] and nōmin [farmers] were still allowed to carry tanto (daggers) as well as short swords known as wakizashi. For many years after the end of the Japanese civil wars, though, commoners did not always abide by the laws prohibiting swords. One reason was that the actual measurements used to define katana, wakizashi, and tanto were confusing and often inconsistently applied in many of these laws. Thus during the early part of the Edo period (early1600s), some chōnin, and especially yakuza, or criminal gang members, openly carried long wakizashi that were virtually equivalent to prohibited katana.”

It was not until 1645 that a law defined the maximum blade length of katana as 2 shaku 8 or 9 sun (33.5 to 34.5‑inches/85.5 to 87.5 cm) and wakizashi as 1 shaku 8 or 9 sun (21.5 to 22.5‑inches/55.5 to 57.5 cm). [figures and conversions from Cunningham]

In 1668, chōnin were restricted to carrying ko‑wakizashi of blade no longer than 1 shaku 5 sun (approximately 17.5 inches or 45.5 cm) without official permission. There was no restriction on a commoner wearing a ko‑wakizashi, but it was unlikely for the weapon to be worn when on day‑to‑day business.

Later amendments permitted the carrying of “full‑sized” wakizashi under certain circumstances, such as travel and fire.

A travelling commoner was allowed to carry a wakizashi as a defence against robbers.

Fires were common in feudal Japanese towns. Commoners forced from their homes by the threat of fire were permitted to carry wakizashi to protect what other possessions they had managed to carry with them.

Serge Moll, in “Classical Weaponry of Japan” (p.19) notes an alternate name for a short sword was “dochuzashi”: “Dochu literally means “while on the street” or “while on a journey,” so one could describe a dochuzashi as a short sword inserted in the sash while one was traveling.”

The characters commonly used to spell wakizashi may be read as meaning “insert at the side”. The practice of wearing the daishō was termed “nihonzashi” (“insert two (swords)”)

Moll also gives a definition of ko‑wakizashi as between 30 and 40 cm, and that longer ones (up to 60 centimetres) were called Owakizashi (“big wakizashi”)

Doubtless, a commoner would avail themselves of their wakizashi or ko‑wakizashi in the event of a burglary or home invasion.

The short swords owned by commoners were probably more utilitarian and lower priced than that owned by a prosperous samurai. For every famed Japanese swordsmith, there were probably scores of blacksmiths turning out commoners' blades.

What is in a Name?

Time I addressed the topic of terminology.

Some Wikipedia articles and other websites use very narrow definitions of some of the terms that have been used in this article. A wakazashi is this! A kodachi is a quite different thing and is this! And so on. There is little credible precedent for these narrow and exact definitions, and they may prove counterproductive to your actual understanding.

We are talking a considerable period of history, large geographical area, varying levels of education and often no centralized system of standardization.

The distinction between tantos, kodachi, wakizashi, shotō etc are in practice less distinct and more fuzzy than is represented by some modern writers. Often these terms were used interchangeably or with a degree of overlap.

Moll: “The meaning of the terms “long sword” and “short sword” changed over the centuries. Nowadays, all swords that are shorter than two shaku (approximately 60 centimeters)! but longer than one shaku (approximately 30 centimeters) are called shotō, or “short swords.””

This definition nicely encompasses all wakizashi, but also includes some tantos and other Japanese knives. Moll also notes some ryu define their kogusoku/kodachi techniques as being for tanto and short swords of “up to 36 cm length”. Other ryu consider kogusoku/kodachijutsu to be methods for tanto/knife and/or short sword and it is quite probable in some cases the latter refers to wakizashi.

Some of you will know the “‑to” part of the term tanto actually designates that the hilt has a sword‑type guard. You will see some sources refer to tanto as “short swords” or “swords”. Other identical forms and sizes of Japanese blade, fitted to different varieties of hilt, are never called a sword. This is confusing to a reader not aware of the word's origin, when the weapon is clearly a knife or dagger in form and function.

“Dagger” itself is a problematic term, since it has been misappropriated and misused by the legal systems of certain American states, creating the false impression that the term only applies to double‑edged weapons.

Cameron Stone observes the term seems to be applied to any variety of knife, save a clasp knife. (p.198)

Wakizashi in Combat

We have seen the wakizashi/shotō was used by samurai and commoner, and by both men and women. How effective a weapon is it?

If you have ever handled a real, full‑length sword, be it Japanese or otherwise, you may have been surprised. Length and mass add up to considerable inertia. Keeping such a sword under control needs strength, conditioning and considerable practise.

Fencing swords are a possible exception to the above statement, although it is debatable if those used as sporting equipment should be considered real swords.

A shorter blade, such as a wakizashi or machete, is another thing entirely. They are light and agile.

Moll (p.21) comments that the greater speed of a wakizashi made to more effective than a longer sword against fast attacks by longer weapons such as spear thrusts.

Long weapons such as spears and naginata, tend to have an optimum range within which they are most effective. If one can close within this distance, the advantage of the longer weapon is often lost and the user may be at a considerable disadvantage.

The speed of a wakizashi improved the chances of parrying an initial attack so that distance could be closed. The wakizashi's greater manoeuvrability was an advantage when distance was reduced, since it was easier to apply either the edge or point than with a longer and heavier sword.

If using a long weapon and an enemy attempted to close distance, the wakizashi was also a good choice for a backup weapon to deal with close range threats.

One character in Rurouni Kenshin, Aoshi, only uses a kodachi for its superior defensive abilities.

The combination of a long weapon and a shorter one may be seen in some other cultures. The German landsknecht, with his pike, halberd or zweihander wore a short sword called a katzbalger (“cabbage cutter”). The huntsman with a boar spear often wore a long wood knife or hanger.

The wakizashi is short enough to be used for the close‑range fighting techniques of kogusoku/kodachijutsu but long enough to use the daitō techniques taught in kenjutsu.

The lighter weight and reduced inertia made a wakizashi more responsive and effective than a longer sword if used in one hand. Its ability to be used one‑handed and shorter length allowed use of the wakizashi to be combined with strikes and grappling attacks from the other hand. The use of a wakizashi could be combined with weapons wielded in the other hand, such as a jutte, tessen (fan), tanto or manrikigusari.

The wakizashi was also a more practical weapon to use in one's weaker hand. Nitoken was often practiced with the wakizashi in the left hand and a katana in the right (all Japanese swordsmen were taught to fight with their right hand as primary). Figure 1-8 of Moll's book shows nitoken using a kodachi in each hand, an interesting variation with considerable potential, particularly if used with the principles of long har chuan.

Being shorter and lighter, a wakizashi may be drawn in less time than a longer sword. I suspect the wakizashi will often taste blood while the katana is still leaving the station. I have come across references to Japanese bodyguards wearing short blades in full‑length sheaths as a deception.

As we have seen, the wakizashi might be used for combat indoors, and seems well suited for the purpose. Using a katana indoors may not have been as practical and elegant as the movies make it seem. A traditional Japanese ceiling was only 220 to 240 cm high, which must have hindered some of the classic kenjutsu moves. How many samurai embedded their katana in a rafter and fell victim to a wakizashi, one wonders. Not all the walls were paper, so narrow corridors may also have hindered a swordsman too.

One begins to appreciate why the ninja favoured short blades for their ninjato.

This is doubtless the reason why the machi-kata dōshin described above carried a blunted wakizashi and not a katana. There was a good chance he might have to fight indoors, and a wakizashi‑length weapon was superior to a katana in such locations.

This more in‑depth look at the wakizashi has made me think about other warriors that used short weapons, such as the Egyptian with his kopesh, and the Roman with his gladius. The shorter gladius was obviously handier during the close press of massed combat. Did it also over an advantage parrying against spears and longer weapons? Shaka invented the short ilkwa, giving the Zulus a significant advantage over most of their enemies.

I have liked wakizashis from the first time I handled one. The above research and analysis shows my initial gut reaction was not off target.

I have also learnt they have a much broader and significant history than is generally known. It was an important weapon for commoner and noble alike.

The wakizashi is overshadowed by the katana. Short swords don't look as good up on the screen as long ones. The wakizashi is probably a much more practical choice, particularly those of use who do not have the necessary time needed to master the inertia of longer weapons.

I have a replica wakizashi that is of particular interest. It has a 20 inch blade and an eight and a half inch grip.

Not particularly long‑bladed for a wakizashi, but long enough for most tasks I might ask of it. It is longer than many machetes, for example. It only looks short if you put it alongside a full‑length katana. The shorter weapon handles much better.

The eight and a half inch handle is a nice feature. This is longer than is found on some wakizashi, and gives a shade more leverage when using two‑handed techniques.

The Japanese blade shape is widely recognized as an efficient design. There is good reason it changed little for hundreds of years. Slightly curved for a more effective cutting action, straight enough to allow the point to easily be brought into action.

I have a modernized “ninjato” of similar dimensions. Grip a shade longer, blade a little shorter. People who have handled this sword react very positively to it, often surprising themselves. It just feels right!

I have a better quality wakizashi, longer blade and shorter grip. The oval section of the handle is less sharp and more comfortable, but it is the 20+8 that feels right.

A typical single doorway is 28 inches wide. Unless, for some bizarre reason I hold my wakizashi sideways and horizontal, a doorway is little obstruction to me when holding a wakizashi.

If, by some freak of chance that I ever have enough money to have a sword custom made for me, I think I might actually opt for a 20 inch wakizashi with an eight and a half inch grip. It is probably a far more practical and versatile option than a longer weapon.

Many years ago, this blog looked at Marc MacYoung’s suggestion on using a sword for home defence. To the comments already made there, I will add that you pay special attention to length and inertia. The reasons for my saying so should be obvious by now.

In some parts of the world, pointless local laws may prevent you owning a katana unless you are rich enough to buy antiques. Some of these laws permit a blade of 50 cm or less, which ironically may result in you getting a more effective weapon!

Many years ago, I read an article where the author noted that if you did want to own a genuine antique Japanese blade, buying a wakizashi might be the better option, since prices were often more bearable.

Wakizashis are not your only choice, of course. Many of the benefits already described also apply to machetes, barongs, kindjal, goloks, hangers, falchion and kukris, to name just a few.

To finish, a rather nice video:

There are several things to note here.

Note how the wakizashi attacks and defences come from a low position. This will be familiar to some of you from the baton, entrenching tool and machete techniques in “Crash Combat”. This is much more useful than waving a weapon around over your head.

Note the wooden wakizashi is gripped a short distance below the guard, protecting the hand from any forceful blows the guard may take.

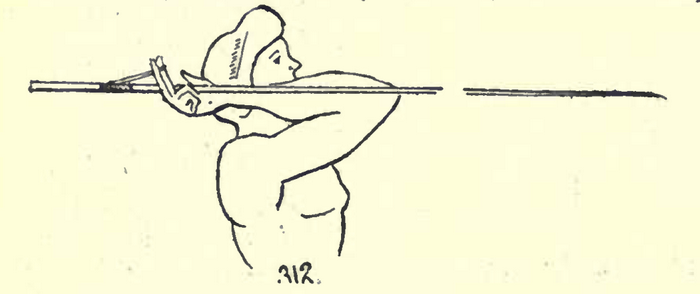

Also, note how the wakizashi allows one hand to shield the eyes against the sun while the polished surface of the blade would be used to reflect sunlight back at the attacker's eyes.