In my recent post about throwing sticks and stones, I mentioned that creating a good spear was not as easy as some survival manuals make out, and that the throwing stick might be a better investment of your time and energies.

I had wanted to link this comment to an article that I had written back in my early days on the internet. However, the throwing weapons group I had originally written it for had long since disappeared, and to my surprise, I had not placed a copy on my other website.

Since then, I have discovered several of my original articles are preserved on this site.

The spear article, in turn, referenced an article I wrote on throwing arrows, so I have updated that and reposted it here.

Throwing arrows, or at least javelins that resemble arrows, have been used by several cultures, including the Romans and the Plains Indians.

One form of Roman weapon, the plumbata, is described as being about 10 inches long with an iron head, lead or lead‑weighted shaft and tin fins. There are references to legionaries carrying a rack of such missiles on the inside of their shields, at least in some regions or periods of the empire.

The Celts are known to have used a hardwood and iron weapon of about 21 inches length. (These are the weapons termed “Irish darts” in “Slash and Thrust” by John Sanchez. Sanchez claims these were the inspiration for the lead, iron and tin Roman dart. The example of the latter that he illustrates differs from most modern reconstructions.)

By the Middle Ages, such short spears or darts were also popular in other regions, particularly with the Arabs and Spanish (no doubt with the latter due to Moorish influence). “Spanish Darts” were one of the many weapons Henry VIII was proficient with. “Top dartes” were thrown from the rigging of warships.

Hand‑thrown arrows are sometimes referred to as “dutch arrows”.

This article will deal with less conventionally thrown arrows.

In his book “The Art of Attack”, H.S.Cowper refers to a class of weapon that he calls “javelins”, although he concedes the term is also used for conventional spears.

Cowper uses the term javelin to define "“…short pointed missiles flung by the wrist, not propelled straight by the forearm, but twirling in the air end over end before striking the object aimed at”. In other words, something that looks like a spear but is thrown like a knife.

Most of these weapons he describes are between one and three feet in length.

Obviously, this use of the term “javelin” has fallen into disuse.

Cowper suggests such a javelin was the type of weapon Saul threw at David: sitting around the throne room with a full size spear and throwing it a such short range seems to him unlikely.

Cowper describes several examples of javelin:

The Persians used an all metal weapon 2.5 feet long, and sometimes carried two or three in the same sheath. The Arabs used the “mizrak”, which had a 15 inch head, 23 inch shaft and a spiked butt.

The Greek version had a head at each end, but then so do certain much longer Greek spears.

The Knights’ Armoury at Malta had large stocks of sticks with a spear point at each end. These two foot long weapons were intended for throwing from the walls.

Most of the two‑pointed weapons have one head smaller than the other. It is true that this is a feature seen on many double pointed throwing knives, but it is just as likely the lesser point is for close combat or sticking the thing in the ground.

Short throwing sticks with a point at each end date back to prehistoric man.

Two‑pointed examples certainly exist, but the majority of these weapons are single‑pointed, and single‑bladed tumbling weapons seem to have seen very little battlefield use .

Cowper's javelins resemble short spears or throwing arrows, but are thrown end over end like a throwing knife. Pretty obviously, it is hard to tell by looking if a short spear was thrown knife fashion or spear fashion, and in many cases the answer may be either.

I have seen suggestions that the Roman plumbata may have been thrown like a German stick grenade.

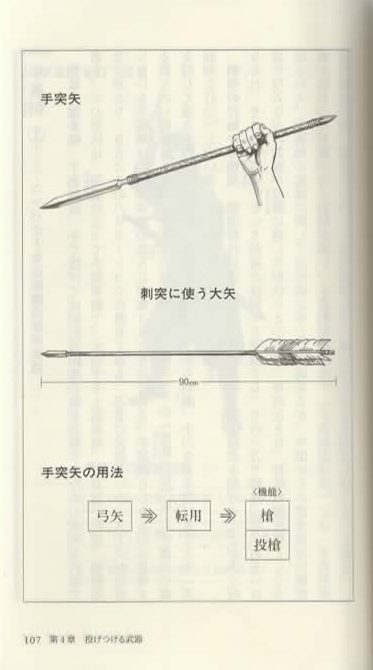

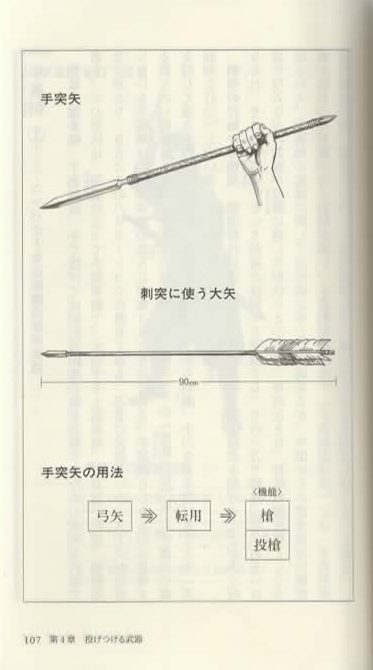

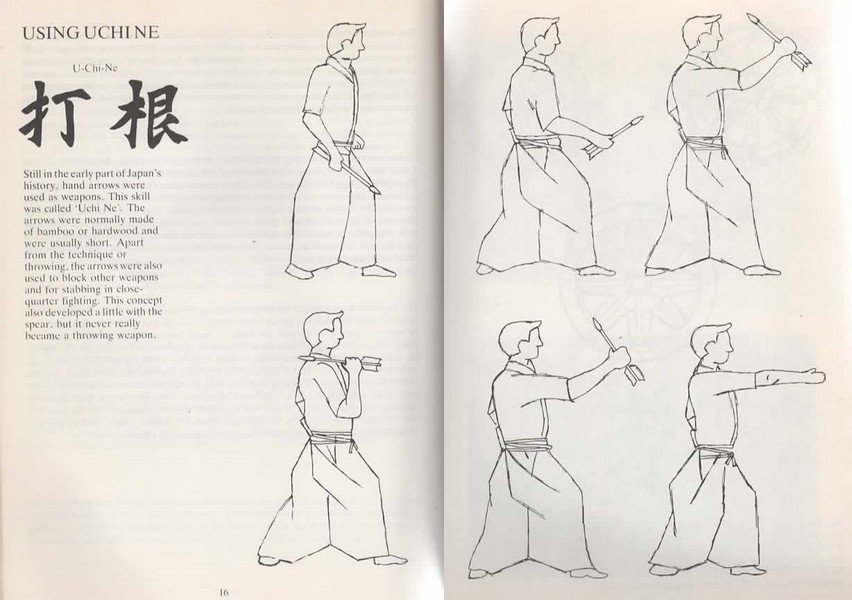

The best evidence for such missiles being used that I have found comes from Japan. The “uchi‑ne” resembles a short stocky arrow about 12 inch long with a 4 inch head.

The “nage‑yari” (“thrown/throwing spear”) is a short spear about 17 inch long with a 5 inch head. Often tassels are fitted behind the head, which may aid drag stabilisation.

According to some books, these short missiles are used in the defence of palanquins.

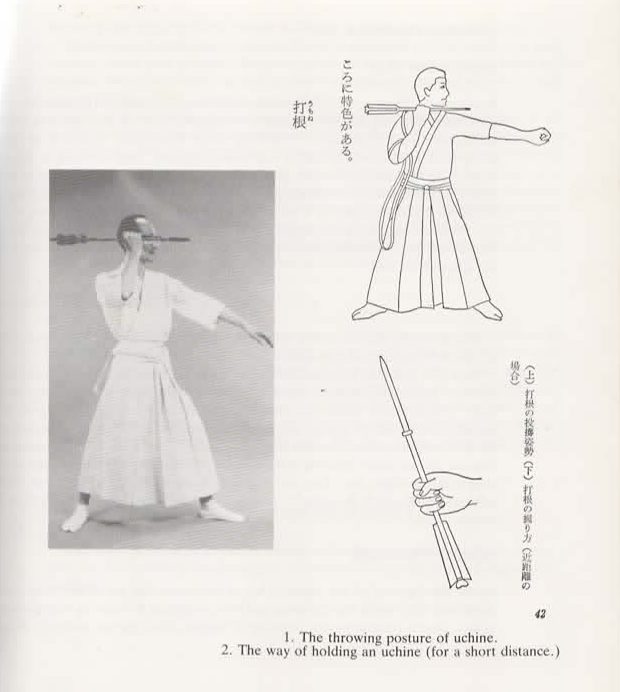

Michael Finn's book “The Art of Shuriken” plainly shows an uchi‑ne being thrown in the same way as a knife, but holding the bottom of the shaft just above the vanes. Finn’s illustration appears to show an uchi‑ne brought up to touch the shoulder and then flipped forward by straightening the arm.

Don. F. Draeger, in “Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts” lists “uchi‑ne jitsu” as a skill practiced by samurai.

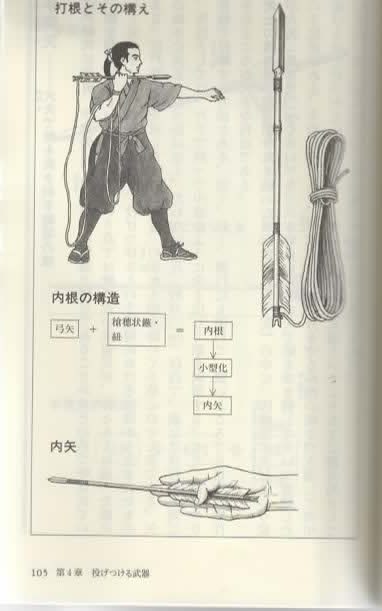

In Shirakami Ikku Ken's book “Shuriken‑Do”, there is also an illustration of uchi‑ne throwing, but this arrow is about two and a half feet long, and obviously thrown as a spear. Interestingly, this illustration also shows a retrieval cord, and the text mentions that some uchi‑ne are fitted with these. Shirakami tells us that for long ranges the uchi‑ne is thrown like a spear, but for shorter ranges it is gripped differently and thrown in a turning style.

Interestingly, Shirakami precedes this description with a few words on more conventional Japanese throwing spears, which he terms “uchine” (spelt without a hyphen).

Most illustrations of uchi‑ne that I've encountered have been of the shorter variety, however.

The uchi‑ne was obviously intended to fly point first, and there is some indication that the nage‑yari was drag stabilized: the shaft appears to be tapered and there seems to be a tassel behind the head.

The question that intrigues me is were nage‑yari thrown like spears or like knives, and did they have enough drag stabilization to fly point first or did they tumble as Cowper assumes?

These weapons pose several questions which are worth investigating.

- How long a shaft is needed to get a knife to fly point first? This will of course vary with head length and mass. Could a formulae to predict the length needed be found?

- Will adding a shaft to a knife significantly increase its range?

- Will adding a shaft to a undersized or too light knife turn it into a more effective missile?

Sadly, I don't have the room nor resources to experiment with these ideas at the moment, but would like to hear from anyone who decides to give them a try.

In addition to wood, a good shaft material may be plastic pipe.

Throwing with Strings

In his book “The Crossbow”, Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey describes arrow throwing as it was practiced by pitmen of the West Riding region, Yorkshire.

Where the Yorkshire technique differs from most arrow throwing is that it uses a length of string.

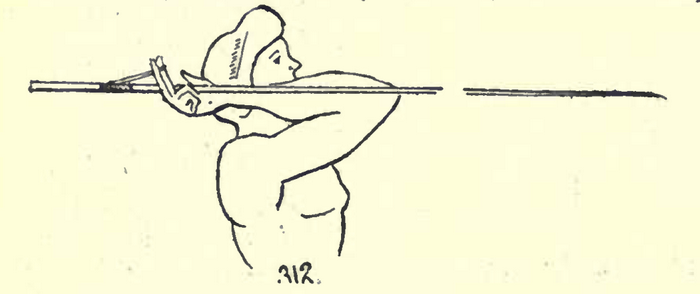

This string had an overhand knot tied at one end and this end was attached to the arrow by means of a half hitch. Hitching point was 16 inches back from the head, just behind the centre of gravity. The other end of the string was wrapped around the index finger of the throwing hand.

The arrow was then grasped just behind the head with the thumb and second and third fingers, the index finger keeping the string taunt.

The arrow is thrown like a spear, but the string increases the efficiency/duration of energy transfer. (I'll leave it to a physics teacher to explain this better!)

As the arrow leaves the thrower, the half hitch unties itself and so the string stays with the thrower.

The arrows used were 31 inches long, with an ogival tip and 5/16 of an inch wide at the head end. The arrow tapered to a point 3/16 of an inch wide at the back end.

Centre of balance was 13 inches from the head.

The entire arrow would have weighed only a little more than half an ounce. Usual material was hazelwood with a pith core. This would be dried for two years before being used to make an arrow.

A good arrow was highly prized by its owner.

The purpose of this arrow throwing was for amusement and competition.

An typical throw ranged from about 240 to 250 yards, although the better throwers may manage 280 to 300 yards.

The longest recorded throw was 372 yards.

As an experiment, Payne-Gallwey asked a thrower to use this technique with a flight arrow from a bow. A range of 180 to 200 yards was achievable. Given Payne-Gallwey's other interests, I suspect that the arrow used was a Turkish arrow which would have weighed 7 dr, or 7/8th of an ounce.

The arrows used in Yorkshire were not used for hunting or war, but the technique of throwing a missile further with a length of cord was used in a more belligerent manner by other cultures.

Natives of the New Hebrides, New Caledonia and New Guinea used a device called the “ounep” by Cowper.

The only difference between the ounep and the Yorkshireman's string is that the ounep was used on full‑sized spears and the hitch was tied at the centre of gravity rather than the butt.

The finger end of the cord might have a loop tied rather than just being wrapped around the finger.

The ounep allowed a spear to be thrown further, and theoretically a thrower would not be in danger from a return cast unless the enemy had a ounep of his own.

The principle of the ounep was known to the Greeks and Romans, although they used a loop of cord tied permanently to the shaft. This was known as the “amentum” (thong or strap) to the Romans and the “ankulé” to the Greeks. This device was used by the javelin armed pelasts of the Greek world.

A comparison of hand‑throwing, ounep, amentum and atlatl spear‑throwing would be interesting.