Reams have been written about the bayonet in the last one hundred years. Several US Army manuals begin by talking about “the Spirit of the Bayonet”. Much is written about the psychological effects training and using the bayonet is supposed to induce. We are even told “the bayonet is irresistible”.

As I noted in an earlier post, the practicality of the bayonet as a weapon was being questioned as early as the introduction of breech-loaders. Once machine guns became common, one would think the matter had been settled. Not so.

The Bayonet en Mass

Part of the problem with examining this topic is that many writers fail to distinguish between the use of the bayonet in massed charges and its use in personal combat.

Many bayonet manuals do not give much space to how a massed charge is to be actually conducted. Perhaps this was covered in other manuals. A US Army manual from 1916 informs troops that they should walk most of the distance to the enemy position so as not to unduly tire themselves. At 30-40 yards distance they may begin to move at double time, and rush the last few yards. A British manual from 1942 urges troops to approach the enemy position using all available cover. When reaching 20 yards distance, the unit was to form up for the charge and rush the final distance. When conducting massed charges it was felt important that a line formation was maintained. Given the effects of adrenaline and irregular terrain, this may not have been practical in many cases.

If one can approach to within 20 yards of an enemy position, there were probably better options than a bayonet rush. The position could be attached with multiple grenades, and automatic weapons used to sweep the visible sections of trench, for example.

Sir Basil H. Liddell Hart said:

“There are two thousand years of experience to tell us that the only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind is to get an old idea out.”

The conventional military mind seems to have retained its fascination with the bayonet charge long after such tactics should probably have been retired. Certainly bayonet charges have been used since the Second World War. Charges were used in the Falklands War, and in Afghanistan.

Hill 180 Korea

One of the last great bayonet charges, for American forces at least, was the bayonet charge by Easy Company, 27th Infantry Regiment, against Hill 180.

“Commentary on Infantry Operations and Weapons Usage in Korea, Winter of 1950-51” by SLA Marshall has a chapter on the utility of bayonets, and the following observations about the attack on Hill 180:

“The tactical omissions, which accompany and seem to be the emotional consequence of the verve and high excitement of the bayonet charge, stand out as prominently as the extreme valor of the individuals. . . The young Captain Millett, so intent on getting his attack going that he “didn’t have time” to call for artillery fires to the rearward of the hill, though that was the natural way to close the escape route and protect his own force from snipers who were thus allowed a free hand on that ground. . . His subsequent forgetting that the tank fire should be adjusted upward along the hill. . .The failure to use mortars toward the same object. . .The starving of the grenade supply, though this was a situation calling for grenades, and the resupply route was not wholly closed by fire. . .The fractionalization of the company in the attack to the degree where only high individual action can save the situation, and individual ammunition failures may well lose it.

It cannot be argued that bayonet charges have not worked. And yet, one cannot help but wonder just how many lives have been needless expended because a massed bayonet charge was attempted rather than other more practical options. For a young officer the bayonet charge seems a gamble between a medal or a court martial. If they survive.

Individual Bayonet Use

Let us move to the more practical topic of the use of the bayonet as a personal weapon. In the second edition of “Crash Combat” I suggest that the use of the bayonet, or other close combat means are only attempted if the threat is within three body lengths. If the distance is greater, seek cover, reload and shoot, or some other tactic.

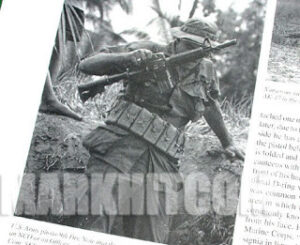

Older manuals recommend the bayonet be used for night combat where muzzle flash might expose your location. It is also to be used in close quarter situations where any firing might endanger comrades.

Three to four kilos of rifle does not make an ideal spear handle. It is, however “what you got”.

To use a bayonet, you must have a bayonet. Most modern bayonets are overweight supposedly multi-purpose tools of little actual utility. Understandably, many soldiers have discarded them in favour of more useful blades.

I won’t discuss techniques for unbayoneted weapons, since these are covered in my books.

When to Fix Bayonets

Assuming you have one, when should you fix your bayonet? Wartime British manuals require the bayonet to be fitted whenever the enemy is within 300 yards. Sights for shorter ranges were set to compensate for the changes the fitted bayonet made on point of impact. The Russians took this further. During wartime the Mosin-Nagant was always fitted with its bayonet. A fitted bayonet is necessary to zero the sights.

In a more modern context, it may be prudent to fix bayonets if engagement range is less than 50 metres.

The Indoor Bayonet

A fixed bayonet may seem a handy thing to have when sweeping a house. As well as its defensive use it can probe under beds or into other dark places. Bert Levy comments that within a building, bayonets are more a hazard to comrades and likely to get frequently caught on furniture. Levy was probably referring to sword bayonets mounted on relatively long bolt-action service rifles. Experiments need to be conducted to determine the best ways for teams to move with modern bayoneted weapons within building interiors. Since shooting will remain the primary offensive mechanism, this will probably be a low-ready position, rather than the high-port usually required for moving with bayoneted weapons.

À la Bayonet

Recently I read an entertaining and informative paper on the bayonet. Unfortunately the author devotes a big chunk of his discussion to perpetuating the bayonet wound fallacy. Later in the paper he graphically describes how visceral and final an encounter involving bayonets may be. It does not occur to him that this may be related to why there are so few bayonet wounds in the field hospital. Most victims never make it that far! Near the end of the on-line version of the article he states: “The Military Manual of Self-Defence (55) offers a series of aggressive alternatives to traditional bayonet fighting movements, its focus more on disabling the opponent than parrying until a clean point can be made. While not necessarily offering a full replacement to classic bayonet training, it does show that more options exist.”

This did amuse me. Firstly, The Military Manual of Self-Defence (Anthony Herbert) unashamedly copies entire sections from other works. Most of the bayonet section is taken from “Cold Steel” by John Styers USMC. The illustrations even still look like Styers! Styers, in turn, drew directly from Biddle (“Do or Die”), who was an instructor for the USMC. This “untraditional” system was that taught to most marines.

There is also an amusing irony here. During his military service, Herbert was wounded fourteen times. Three of them were from bayonets!

derived from a civilian tool favoured by outdoorsmen. Hangers, “short hunting swords” or “couteau de chasse” were useful for chopping firewood, clearing brush and butchering game. They were carried by noble and commoner alike. There are exciting accounts of them being used to hunt game and they were a useful defence against both beast and man. Decorated versions might be worn out court to display one’s affection for hunting. They might also be worn in town as a handy defence against robbers, in many cases being more effective and convenient than rapiers or small swords. Understandably the common foot soldier found the hanger to be a useful implement. In addition to the sword bayonet the hanger is probably the ancestor of both the naval cutlass and the machete, and is why you occasionally come across machetes referred to as cutlasses. Sword bayonets were created to produce a bayonet that also served as an infantryman’s hanger. The yataghan configuration blade provided better clearance for the hand when reloading a muzzle-loading weapon. The blade shape is not without other merits so a number of breech loaders also used sabre bayonets.

derived from a civilian tool favoured by outdoorsmen. Hangers, “short hunting swords” or “couteau de chasse” were useful for chopping firewood, clearing brush and butchering game. They were carried by noble and commoner alike. There are exciting accounts of them being used to hunt game and they were a useful defence against both beast and man. Decorated versions might be worn out court to display one’s affection for hunting. They might also be worn in town as a handy defence against robbers, in many cases being more effective and convenient than rapiers or small swords. Understandably the common foot soldier found the hanger to be a useful implement. In addition to the sword bayonet the hanger is probably the ancestor of both the naval cutlass and the machete, and is why you occasionally come across machetes referred to as cutlasses. Sword bayonets were created to produce a bayonet that also served as an infantryman’s hanger. The yataghan configuration blade provided better clearance for the hand when reloading a muzzle-loading weapon. The blade shape is not without other merits so a number of breech loaders also used sabre bayonets.