In my blog on foundation survival equipment, two of the items were a rain poncho and a blanket. Given how expensive good blankets are these days, many of you will have opted for a poncho-liner (aka “woobie”) instead.

Why a blanket/poncho-liner rather than a sleeping bag? A good sleeping bag is well worth having. In warmer conditions, however, a poncho-liner may be a better choice than that bulky five-season expedition bag you just had to buy, “just in case”. In colder conditions, a poncho-liner may be combined with a sleeping bag of more modest (and more practical) capabilities.

In case you have not worked it out, a more practical sleeping bag purchase would have been a two or three-season bag that can be combined with other items in colder weather, including another sleeping bag. Generally, several thinner layers trap more warm air than one very thick one.

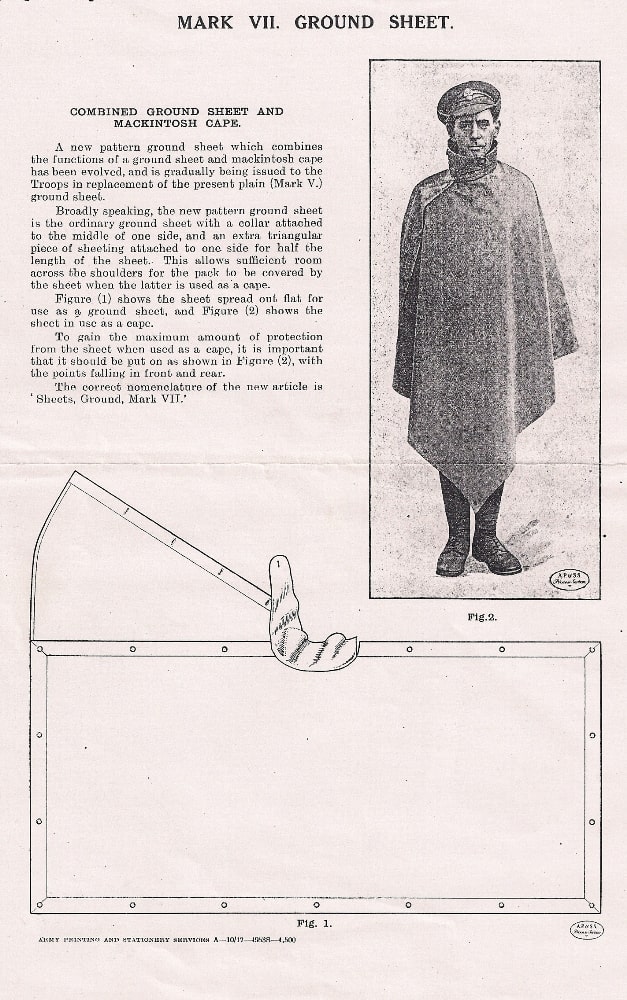

The poncho-liner was designed to be part of a warm weather sleeping system. The instructions are that the poncho-liner is to be tied to a GI-issue rain poncho, with the rain poncho outermost. The soldier lies on one half of the combination and folds the other half over themselves. The snaps (poppers) on the rain poncho should not be used to fasten the opening if sleeping in a combat zone.

Tying the liner to the poncho may not be necessary. Threading the tapes through the eyelets may keep things together by friction alone.

Easiest knot is to make a loop at the base of the cord and pass it up through the eyelet. Make a loop higher in the cord and take it over the edge of the pooncho and pass the loop through the first. Hold the free end and pull the other side of the second loop to pull the first loop snug. This is very easy to tie and easy to undo with cold, wet hands. This is “two-thirds of a Highwayman's Hitch”.

The above method of using rain poncho and liner together has become known as a “ranger roll”, not to be confused with the packing method of the same name. It has been pointed out to me that this system resembles an Australian swag, with the obvious difference a swag uses heavier but breathable canvas,

Ironically, the best way I have found to pack a poncho roll is the other kind of ranger roll.

The poncho and liner (presumably as a ranger-roll configuration) is designated as a sleeping system for temperatures above 50°F (10°C). Put another way, if your breath is fogging, make more elaborate sleeping arrangements.

Rigging your rain poncho as a shelter, such as a ridge tent or lean-to, will trap a layer of air above while you sleep wrapped in your liner. You will be better ventilated and more comfortable than the ranger-roll. Where tactically possible, a fire may be built before a lean-to.

Insulating yourself from ground-chill will also facilitate sleeping at lower temperatures. Place hay, browse, bracken etc between yourself and the ground. Wreckage such as seat cushions may be used. If you have an insulated kip-mat, it may be used instead of or in addition to the previous measures.

If you want to use your poncho as a shelter you will need to carry some cordage, pegs and possibly poles. The two hanks of cord I recommended adding to your EDC will do fine. Since most ponchos or liners do not have a waist cord such cord may be knotted around the waist when wearing a rain-poncho and/or poncho-liner. Bungee cords are an alternative to cordage for shelters, and may also be used around the waist if your brought them long enough.

Some ponchos only have eyelets at the corners, or even lack these. Fit eyelets to each corner and the centre of each edge.

There are alternate options, of course. One of them is a bivi-bag and a pair of poncho-liners.

A poncho-liner is a sensible thing to acquire, even if most of the time you just throw it over yourself when watching telly in the colder months.

Useful though the poncho-liner is, there is room for improvement.

Below is a video of “Green-Craft's” poncho-liner improvements:

Personally, I found some of the modifications described hard to fully comprehend. Long, verbal descriptions on a video are not the best means of communicating information. The video could have benefited from some more illustrations and written lists.

I decided not to use many of these suggested modifications.

For one thing, I do not like “hand-warmer” pockets. Move with your hands in your pockets and you cannot defend yourself nor save yourself if you fall. Essentially, hand-warmer pockets are diametrically the opposite of what this blog is about.

I also had concerns that some of these modifications would affect the packability of my poncho-liner.

And I am short on funds, so cannot afford all the bits needed for the modifications even if I did want them.

The Head Hole

Why did the inventors of the poncho-liner not include a head hole so that it could be worn under a rain-poncho?

Perhaps it was something to do with the commitment to the war in Vietnam? Warm clothing was not seen as a high priority?

Modifying your poncho-liner so that it can be worn as a real poncho is probably the most useful modification you can make, and it is relatively simple.

You will need:

• A 40 cm open-ended zip of suitable colour and finish

• About a metre of suitably coloured double-fold bias tape

• Sewing supplies. A needle, suitably coloured thread, pins, chalk, scissors/shears, a tape measure.

You do not want a zipper with shiny nor reflective teeth, so you will probably get a plastic zip. Colour and shades should be one that blends well with the basic appearance of your poncho-liner.

My poncho-liner is in German Tropentarn desert camo (aka “desert flecktarn” or “fleckdesert”), which is actually quite a good general-purpose pattern. Thus I brought a zipper described as beige.

I brought my double bias tape and the colour was described as “stone”.

If you have some scraps of suitably coloured or patterned material you can make your own bias tape by cutting it diagonally. Using different scraps will enhance the disruptive effect.

There are videos on how to make bias tape and how to join the different sections. You will need and iron and possibly a former.

The Cut

Decide which side of your poncho-liner will be the “outer” and which the “inside.” Also decide which part will be “front” and which “back”. My poncho-liner has a label in one corner so I arranged it so that this would be inside and at the back.

As evenly as possible, fold your poncho-liner width-wise. Then fold it lengthwise. The corner of the folds should be the centre of your poncho-liner.

Many blogs ago, I advised you to buy some chalk and add it to your EDC. You probably had several sticks left. Add some to your home sewing kit, it is times such as these it comes in useful.

Measure down from the centre corner 8 cm and mark a spot with your chalk. Make an 8cm cut through both thicknesses of the poncho-liner. Note that the cut you are making is lengthwise, going from back to front.

Unfold the poncho-liner. From the edge of the cut measure 19 cm and mark a point with chalk. I used a set-square here to ensure the line was perpendicular to a width-wise fold. Cut down the front 19 cm.

You now have a poncho-liner with a 35 cm hole in the centre. Check this fits easily over your head. Make it a shade bigger if necessary.

Fitting the Zip and Collar

Unzip your zipper into separate halves.

On the outermost side of the poncho-liner, place your zipper parts on either side of the head-hole.

Position them so that for each the teeth are on the opposite side to the opening.

You should be looking at the “back side” of the zipper and the puller should be on the front-side of the poncho-liner when fully down.

Pin each of the zipper halves so that the toothless edge is flush with the cut edge of the head-hole.

Note that your zipper is longer than the hole you cut. Make sure they are closely aligned. Try closing the zipper while it is still only pinned in position and adjust as necessary.

Fitting the Double Bias Tape

Once you are happy with the position of your zipper, you need to pin the bias tape into position.

I suggest you watch a few videos to familiarize yourself with how this tape is used. We are going to fold it all the way over the edge of the head-hole. If you look at the outer edges of your poncho-liner you will see a similar method has already been used to finish that edge.

Cut two lengths of bias tape about the same length as your zipper. Unfold the tape so that you are looking at its “inside”.

Place the tape, inside uppermost, over your zipper half. Align the inner edge of the tape so that it is flush with the cut-edge of the poncho and the toothless edge of the zipper. Pin in position and repeat for the other side.

You can remove the pins you put in to hold the zipper.

There should be pins securing both tape and zipper to the poncho-liner.

Note that if I was to do this again, I would use short lengths of bias tape to cover the top and bottom of the cut before adding the zipper. What I have done does not look too bad (on the outside!), but it could have been neater.

Sewing

I started off trying to use a “mini-sewing machine”. This was very cheap when I brought it. I notice the price is creeping up now!

After attaching the first zipper half I got sick of repeatably rethreading the thing, and realized I could probably do a neater job hand-sewing. Some sections would need to be hand-sewn anyway.

Sew along the crease of the bias tape that is closer to the hole.

Once this is done, fold the tape so that it completely covers the cut edge of the liner and the other crease touches the inside of the poncho-liner, the far edge of the tape tucked in.

Both creases of the tape are thus folded and both edges of the tape tucked in.

Sew just inside the edge of the tape so your thread passes through all four layers of tape, the zipper and the poncho-liner.

Finishing the Zipper

Close your zipper and tuck each end through the cut to the inner side of the poncho-liner.

Finish the ends of the bias tape so they are sewn to the zipper.

Since the top and bottom of my head-hole was untaped, I put a few stiches through the zipper and through the poncho-liner to close off any opening that remained.

Lastly, add a length of cord or tape to your zipper-puller.

Lastly, add a length of cord or tape to your zipper-puller.

This will stop it rattling. It also lets you easily work the zipper if your hands are cold and numb or wearing thick gloves.

If you can get some bootlace that matches the ties on your poncho-liner, that would be cool. I used a length of “desert-camo” 3mm budget paracord, which does not look out of place.

The Zipper Explained

Why use this configuration for your zipper?

When used as a garment, the teeth of the opened parts of the zipper will not contact your bare neck. You can roll the edges of the opening outward if you wish. This is shown in the photo immediately below.

There are other ways to prevent the teeth rubbing the neck, but the above method is one of the simplest and involves very little sewing.

The puller of the zipper is at the front when opened so that you can adjust the neck opening to vary ventilation or retain more heat.

The zipper I brought was described as beige but the actual colour was lighter and more yellow than I had hoped. Because very little of the zipper is visible on the outside, I got lucky and it blends very nicely with the rest of the poncho-liner. I think it may work better than the dark green zipper I also considered.

In practice, the zipper will usually be covered by a scarf or shemagh.

The zipper I brought was missing a tooth at the very top. This caused the puller to jam if the zip is fully closed. Fortunately, by tucking the very bottom and top of the zip, the last few centimetres of each end are not used, yet the opening can be fully closed. A combination of luck and improvisation!

The bias tape I brought was described as “stone” in colour. I was expecting something with a hint of brown, but it proved to be a light, very neutral-looking grey. Not surprisingly, this colour and shade goes very well with both the zipper and the poncho-liner in general.

The camera flash probably creates a greater contrast than the naked eye sees.

Poppers

Once I had fitted the zipper, I went about installing some plastic poppers (aka “snaps”, “snap-fasteners”). These may need special pliers to fit.

You will need something that can poke a small hole through the poncho-liner. I used a stout sailmaker's needle I have in my home sewing kit. A set of these is worth having. The smaller ones go in you EDC or travel kits, the larger into your home sewing and/or repair kit.

You can chalk the needle to make the holes easier to locate.

Getting the Poppers Right

Lay-out your poncho with the inner side upwards.

Mentally divide it into quarters. We will be installing poppers using the following rules. The reason for this will be explained later:

• Each quarter will have the popper halves all of the same time. A quarter will only contain “male” poppers or “female”.

• If a quarter at the top has male poppers, the quarter immediately below will have female, and vice versa.

• If a quarter on the left has male poppers, that on the immediate right will have female, and vice versa.

• Quarters that are diagonally opposite will contain the same type of popper half.

I started off by installing the corner-most popper halves. Concentrate on getting these right and then it is just a matter of using the same popper type for each quarter.

I installed the corner poppers 40mm in from the side edge of the poncho-liner and 190mm from the top or bottom edge. If you are on the large side, place the poppers closer to the edge.

Next, fold your poncho-liner width-wise. Use the top and bottom poppers you have just added if you wish.

From the width-wise fold, measure down 240 to 250mm and install a popper 40mm in from the side. Make sure each quarter of the poncho-liner has the same type popper-half.

When you are wearing the poncho-liner, using this popper forms a sort of sleeve. The opening is generous enough to allow for bulky cold weather clothing. You can also slip your hand in and use it as a hand-warmer, “Fu Manchu”-style.

You will want to add a few more poppers down the side between the “sleeve” popper. I chose to add three more to each side.

With your poncho-liner still folded width-wise, fasten the sleeve and corner poppers. Make another width-wise fold so the corner popper touches the sleeve popper. Mark where the fold is and install a popper. As always, make sure each quarter of the poncho-liner has the same type popper-half.

Install additional poppers between the sleeve and corner poppers and the middle popper you just fitted.

Finishing the Poppers

The poppers I had purchased were supposedly “beige”. They turned out to be way lighter than expected, and had a gloss finish! When installed on the poncho-liner they appeared like they were white.

Luckily, I have some enamel model paints, several in colours close to that of the poncho-liner. I used these to paint the outer sides of the popper halves. I did not bother to paint the inners. I suspect the paint on the inners will either wear off too quickly or affect functionality, but try it if you wish.

For the record, the colours I used were Humbrol no.84 Stone and Revell no.83 Leather Brown. None of the poppers passed through green areas of the camouflage, so I did not use any of my green paints. These are not exact colour matches for the poncho-liner, but if someone is close enough to see the difference camouflage is no longer an option!

Like most painting, a second coat will improve it. You can stipple the surface to produce a more matt-effect, or even sprinkle a little sand on the first coat. However, given that the surface of the poncho-liner is quite smooth, the practical value of this is moot.

While you are at it, see if the poppers on your rain-poncho could use some paint.

Again, the flash on my camera probably shows them up more than the naked eye can discern them.

Below is a shot taken without flash.

You may not be able to avoid painting your poppers, but start off with some that are matt, medium shade and a natural or neutral colour if you can.

The Poppers Explained

Why did I insist such attention be paid to which popper half went in which quarter?

If you want to sleep in your poncho-liner, fold it lengthwise and tuck under the foot-end. You will find you can use the poppers to fasten the free long edges. Much more compact and less bulk than fitting a long zip on this edge!

Personally, I find sleeping like this a little restrictive and am more likely to use the liner like a conventional blanket. Part of the appeal of the liner as a warm weather sleeping system is that it does not confine you like a sleeping bag. Best way to turn the poncho-liner into a cold weather system is use it with a sleeping bag!

Obviously, if the poppers of the rain poncho on a ranger-roll should not be fastened in a threat environment, the same goes for the poppers you fitted to your liner when sleeping.

Wearing your poncho-liner? Two sets of poppers line up to create a sleeve-type opening. Those below can be used to close up the sides.

These simple modifications will take you less than a day, even if you have to hand-sew.

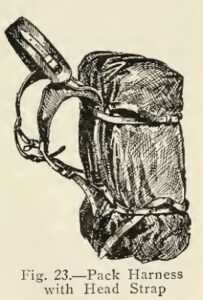

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.