Suppose that you are separated from your bag or rucksack. Your webbing gear, if you wore any, has become damaged or lost. All you have is the clothes you stand up in and whatever is in your pockets. This is your “skin-level” survival kit.

Part of your skin-level kit is the clothes that you are wearing. Hopefully you were dressed appropriately for the climate. If you were chilling by the pool when everything went pear-shaped, one of your first priorities is going to be to acquire some new threads.

Today I am mainly going to concentrate on what you have in your pockets, or carried on your trouser belt. This is what many people would call “EDC” or “everyday carry”, although the exact use of this term varies.

Some people would include the contents of their daysac or handbag in their EDC. This article will assume that such items are not immediately available. Reaching them may be one of your objectives.

Some people use the term “EDC” for all the paraphernalia they have on their person, while in other contexts it is specific for defensive weapons. This article intends to examine EDC for survival.

Look on the internet and you will find EDC lists that suggest you should always carry a solar still, fishing kit, gold coins, eating utensils and so on. This is not very practical.

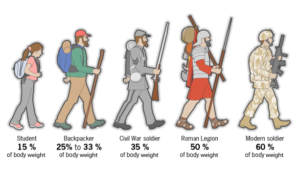

The heavier and bulkier your EDC kit becomes the more likely you are to not carry it all the time and omit parts you may need.

A good EDC survival kit is designed to have two tiers of readiness.

“Lower level” is what you carry all the time. Many of these items are carried because they can be useful in daily life.

“Higher level” are items that you add when you step up to a higher level of readiness.

Your lower-level kit would be on you when you go down to the store.

You would add the higher-level items if you were leaving town to hike in the woods.

For example, in my lower-level kit, I have a lighter, which can be used for fire-making or illumination. The expansion to higher-level is a little pouch that adds a container of tinder, some candles and a spare lighter.

I have little need for a fishing and snaring kit in town, so these items are higher-level.

Many ingenious individuals have had fun creating survival vests, survival jackets, survival walking sticks, survival pens, survival necklaces or survival hats.

These are not the best way of carrying your EDC. Jacket pockets are better used for items such as gloves, scarves and hats.

Your survival EDC should be based around your trousers. Everything should fit in your pockets, or on your trouser belt.

Since you (hopefully) wash your trousers, items should be easy to transfer to a new pair, or to a pair of shorts if the weather permits.

What you carry should not add so much weight that you have trouble keeping your trousers up. Nothing should be so bulky or hard-edged that it digs into you if you have to sleep clothed, bangs against you when walking or might injure you if you fall on it.

Personally, I am seldom not wearing cargo trousers or cargo shorts. If you have to dress more formally, there are companies that sell suitable garments with extra, hidden pockets.

Let us have a look at what I am carrying, and how I might expand it to a higher-level. Your up-level items should be stored together in a small bag such as a pencil case. Keep this with your knife-belt (qv).

Fire: The lighter in my left pocket is my primary source of fire. I have added a couple of birthday candles to my pocket pouch.

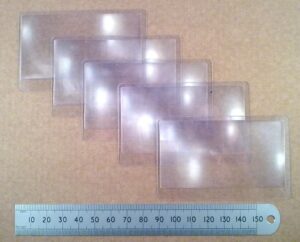

• To up-level, I will use a small fire kit that would be carried in my right cargo pocket. As described on other pages, this would have a spare lighter, a container of tinder, Fresnel lens (above), some candles and possibly some matches.

Note that the spare lighter is in a different pocket to the primary.

Food: I don't carry any food on me, so this category is more about means to procure food. At low readiness that is money and a credit card.

My current location and lifestyle mean that it is exceptionally unlikely that I would find myself needing to feed myself by fishing or trapping. In theory, the dental floss I have in my left pocket pack could be used for snaring or fishing, the safety pins serving as hooks.

Prudence dictates, however, that I should have at least some fishing and snaring capability within my baseline EDC.

With this in mind, I have added a six span length of braided fishing line to my pocket pouch. This may also be used to construct snares and for various other purposes. This line is actually far more likely to see more use than the hooks. It supplements the dental floss and the various lengths of cord and string in my pocket.

Fishing hooks weigh virtually nothing, cost very little and take up very little room, so it would be foolish not to have some for “just in case”. You should have more than your typical survival tin contains.

I have two packs of ten hooks. No.12s and No.10s. (actually, it is a dozen No,12s. I had a pair of hooks from a previous project, so I added these too)

You can buy these hooks already tied to nylon leaders. When you are cold, wet and hungry it is no time to fiddle with tiny hook eyes and near invisible line. If you buy hooks that are untied, add line when you are safe and warm at home.

• If I am knowingly straying far from “civilization”, I would add a kit of additional items. For higher-level, I have a container of line, hooks, wire and other fishing items.

Useful additions would be ten or more metres of snare wire, and several additional lengths of braided line, already fitted with swivels.

For use with the latter, I would have some compact lures, additional hooks and some wire leaders.

A frog/fish gig and a net would be useful, and there are some that might fiti in a trouser's cargo pocket. In general, a gig is more likely to be pack items than skin-level.

If you are diabetic, you may want to add a small supply of glucose tablets, hard-candy etc.

You could carry a tightly rolled sheet of cooking foil, but I personally don't currently do this.

Signalling: I usually carry a phone. As well as being able to call for help, many modern phones have useful applications such as a notepad, compass or GPS capability. Phones are useful but also delicate, so should not be the sole thing you rely on.

The photon light on my keyring could be used to signal. The keyring also has a whistle.

My pocket kit includes a pencil and chalk, and I carry a pen (a retractable Zebra pen, since my belt pouch is rather small. I actually found this pen! Non-retractable, all-steel Zebras are suggested as a good alternative to more expensive “tactical” pens). A permanent marker such as a Sharpie may also prove useful.

• Up-levelling would probably add a larger, but compact, pocket torch.

A lightweight signaling mirror is another useful item. These are a good addition for tactical scenarios since they can be used to peek around cover.

You may already have an item that can be used as a signalling mirror. Many compasses have a mirror and some phones or music players have mirrored backs.

A mini-flare kit could be accommodated with the other items in the right cargo pocket, but I have never actually owned one of these.

A larger whistle, on a lanyard, might prove useful. There are cord necklaces that include a ferro-rod and steel. If you can find them at reasonable price add a whistle, photon light and a snap-link.

Shelter: Most actual shelter items are too bulky for skin-level EDC. The exception is a space blanket. One permanently rides in my pocket kit.

You may want to carry additional space blankets. Not only can they be used for warmth, but also as protection from the rain and for signalling.

Penny for penny and pound for pound, space blankets are among the best survival gear you can carry. Do not leave home without at least one.

Cordage: The dental floss in my pocket kit has already been mentioned. Either carry a couple of spare bootlaces or an arm-span of paracord. This can easily be carried in the bottom of a pocket and has numerous applications. I also carry a tubular retention cord that can be fitted to my glasses if needed.

• If up-levelling, a larger hank of paracord can be carried on your person if you have room. Braided fishing line also has many uses.

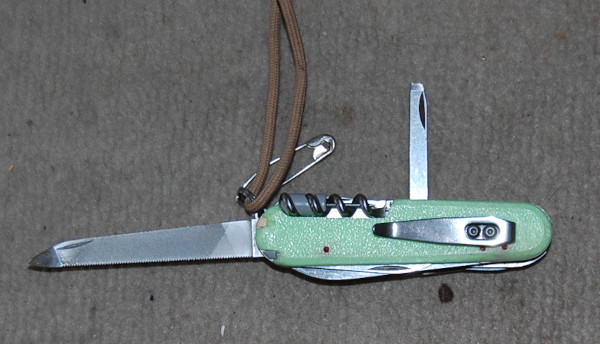

Tools: My keyring includes a bottle-opener, mini-Swiss army knife, a P38 can-opener and a little tool for removing SIM cards and opening CD drives. That last tool possibly does not have a survival application. (It broke, so has been replaced with a paper-clip that can be readily adapted should the need arise),

The keyring itself is a carabiner. Several of my items can open bottles. The bottle-opener is just a convenience, particularly in social settings.

A second pouch has my Swiss army knife, mini-Leatherman, pocket prybar and a sharpening card. I find small-print challenging now, so I have added a tiny pocket-magnifier to this pouch.

The Swiss army knife includes a screwdriver that can repair glasses.

A small bag in my pocket kit contains a few safety pins, hair pins and paper clips. These can be put to various uses.

A length of electrical tape is wrapped around my pencil. I may add a needle with a metre of invisible thread. I don't regard a sewing kit as an EDC-level requirement, but the weight is negligible and a sharp point potentially useful. I have now added a couple of threaded needles, wrapping them around the pencil.

• If up-levelling my main additions would be a larger knife and compass. More of that later.

Water: There are water bottles that can fit in a cargo pocket or on a trouser belt.

The bulk and weight of water means that you are unlikely to carry water at skin level unless the weather is very hot.

A few sheets of water purification tablets can be included in your pocket medical kit.

• If up-levelling the water category, I might add a “survival straw”, ideally one that fits in a cargo pocket. A condom could be used as a water carrier, but I don't carry them, no longer being single.

My pocket pouch is carried within a large Zip-lock bag, which could be used to carry water..

My pocket medical kit rides in my left cargo pocket. In addition to the items already mentioned it has alcohol wipes, plasters and pain-killers.

There is some medication I have to take with meals, so I carry a few days supply of this in my right cargo pocket.

If you need to take medication regularly then you should carry a few days supply with you, and make sure it remains in-date.

• If up-levelling, a small container of insect repellent and/or sun-cream might be a prudent addition. This need only be a small volume, your main supply being in your bag or base. Chapstick or Vaseline in winter, if you think you will need it.

Other items: If you are out in the wilds, a few metres of toilet roll or paper tissues in a ziplock bag should be added to one of your cargo pockets. Make that a permanent part of your kit if you wish.

I have a small bag with a few paper napkins for “about town” and a larger bag I add for “rural”.

A bandanna has numerous uses and is easily carried in a side pocket. Since I lack some hair, I have used mine for head protection when caught out without a hat.

I wear photochromic glasses so don't carry sunglasses. These protect the eyes from both excessive light levels and more physical threats.

Non-survival items carried are a USB drive, travel card and music player, although the back of the latter is a mirror.

So far we have talked about pockets and belt pouches.

In years past most of my EDC was in a compact bumbag. I have learnt to make more use of my cargo pockets and have replaced the bumbag with a couple of pouches attached directly to my trouser belt. One is a repurposed pouch for a mobile phone.

You should not add so many pouches to your trouser belt that it interferes with carrying a rucksack, or sitting in a vehicle.

There are belts that are made of paracord, but if you unravel them to use the cord you have nothing to hold up your trousers, nor hang your pouches from!

There are trouser-belts with hidden storage compartments, and various ingenious buckles. The original boy scout belt had a buckle that served as a bottle opener.

Earlier on I mentioned adding a larger knife and compass to the skin-level kit.

My favorite kukri weighs just under a pound, but hanging it on the trouser-belt is a bit much. What you need is a second belt. This is effectively an intermediate level between skin-level and webbing. When at a higher level of readiness you should attempt to keep it upon your person.

Your knife belt rides below the trouser-belt, like a cowboy's gun-belt. It should be adjustable, so that it can be worn over thick clothing when desired.

Add a compass pouch to one side of the belt, and attach the compass lanyard to the belt. Add a carabiner or snap-link to the front of the belt.

I carry my kukri on one side of the belt and a Mora puukko-type knife on the other. Not surprisingly, this belt could also be used to carry a handgun.

If I need to carry a hatchet or entrenching tool, I can slip it between belt and body.

A folded rain-jacket, poncho or unfolded space blanket can be draped over the back of the belt.

Many police officers experience medical problems from the weight of their duty belts. Detaching the duty belt from the trouser-belt and wearing it lower like a gun-belt might improve matters.

The knife belt can be used to carry a litre or two of water. The best way to carry water is in bladders since this is lighter than conventional bottles. Rather than placing the weight on the knife belt, my proposed “camelbum”concept would give more options.

I have mentioned carabiners and snap-links a couple of times. Use one as your keyring, add one to your whistle lanyard and knife belt. Also have them on your rucksac strap and/or webbing.

When you need a hand free, or there is a risk you might drop a tool, attach the tool to the nearest snap-link.

This is an extension of the idea to collect empty magazines described in my book “Survival Weapons”. Make sure your tools have loops or rings.