A defensive handgun should be the first firearm you acquire.

* Other humans are a far more likely threat than animal attacks or hunger.

* A handgun will defend your person, but may also be used to defend your home.

* A handgun may be carried at times and in places where it is not possible to carry a shotgun or rifle.

* In an emergency, the handgun is a means of defence against most animals.

* A defensive handgun is a more effective hunting weapon than most shooters realise (see later). (Incidentally, your second purchase should be a .22 hunting rifle.)

* A handgun is a useful backup to a shotgun or rifle.

When choosing a handgun it is easy to be swamped in opinion.

If you wish to be logical about your choice, there are several strategies that you can adopt.

Any gun is only as good as the rounds it fires. This is why much of the “movie wisdom” is so farcical. For example, contrary to the advice of at least one movie, a Cz.75 and a SIG P226 fire the same round, and are both excellent weapons for their calibre.

Three Rules for Expanding Bullets

A soft-point or hollow-point load should meet three criteria:

1. The round should be capable of reliably feeding through the mechanism of the weapon using it.

For a revolver or derringer, this may simply be a requirement for the round to fit in the chamber and stay there until fired. Recoil should not case the casing to ride back and foul the gun’s mechanism, for example.

For a round that must feed from a magazine and through a self-loading or other mechanism, the requirements may be more stringent. The bullet must not be deformed or misshapen by loading or firing.

2. The round must have a high chance of reliably expanding at the velocities it is being used at by the gun/ammunition system.

If the round is unlikely to expand, you may be better off shooting solid rounds such as FMJ or semi-wadcutter.

3. Both expansion and penetration is required.

If a round does expand, it should still have sufficient penetration to reach vital organs.

If your hollow-point or soft-point loads give inadequate penetration, you should consider other loads, and be open to the idea that you may need to use non-expanding ammunition.

Choice of Model

Hollywood, video games and even some writers often tell us one model of pistol has a superior performance to another, despite that in real life the two may use the same ammunition!

The chambering of your handgun is probably the first aspect that you should consider.

Once this decision is made, you can select a model based on size, mass, capacity, budget and other factors.

Ideally, you want an automatic pistol of about 7"/180 mm overall length.

As a primary weapon for concealed carry, you want a weapon of small bulk.

As a secondary weapon for overt carry, a weapon of low weight is desirable, since you probably have a rifle or shotgun and enough other things to carry.

What is required is a weapon that is concealable, capable and convenient, both as a primary weapon and as a back-up to a long-arm.

Hence the recommended handgun is of compact/sub-compact size.

If you are shooting someone in defence of your life, you want to make a big, deep hole in them.

Yup, size does matter!

The optimal pistol round for this is the .45 ACP.

The .45 ACP is compatible with a semi-automatic action, allowing for easy and fast reloading.

There was a time when it was hard to find a .45 that was not a large, single-action weapon with a single-figure magazine capacity.

Now we have a variety of compact and sub-compact double-action weapons, with useful magazine capacities.

In “Shooting” (1930), J, Henry Fitzgerald notes that at most ranges game is taken, a handgun is as accurate as a rifle, and more accurate than many hunters can shoot. With reasonable shot placement, a 230gr .45 will do the job a 180gr .30 rifle bullet can. Fitzgerald doesn't bother with specialised hunting guns. He was happy to use his 2" barrelled .45 FitzSpecials. This makes me wonder if a .45 Glock 30 with a 3.8" barrel might be way more versatile than most shooters expect!

Thanks to US military aid, .45 ACP ammunition is reasonably easy to find in many parts of the world.

The standard load of the .45 is subsonic, making it a good choice for general military applications that may include the requirement for weapons to be suppressed.

The Textbook of Small Arms, 1929 notes:

“Rapidity of fire is an essential in pistol shooting, and though the double action of a revolver may well be ignored when it is considered as a target arm, it is of the highest importance when the pistol is considered from the active service point of view as a weapon…

“The value of the calibre of self-loading pistols and revolvers has been much obscured by theory, but practice of recent years has amply proved that small calibre plus high velocity, although developing many foot-pounds of energy, yet lacks stopping or shocking value. There have been many attempts to substitute a high-velocity cartridge of ·38 calibre, as a Service equivalent to the traditional ·455. In practice it has been found that the small calibre sometimes fails to stop its man and that the large-diameter leaden plug of the ·455, moving even 300 or 400 feet a second slower than the high-velocity, small-calibre projectile, is yet far more effective. Recent experiment has, however, developed a new experimental ·38 cartridge [.38/200 of 200 gr] whose efficiency is, so far as ballistic tests can ascertain, not less than that of the ·455.

A hit with a ·455 anywhere literally [sic] knocks an adversary over. This quality of efficiency depends to some extent on the massive soft-lead bullet and the relatively low velocity rather than on any inherent magic in the calibre, for the ·455 or ·45 self-loading pistol firing a lighter nickel-covered bullet at a higher velocity cannot be depended on to produce equal shock effect.

The efficiency of the ·455 revolver cartridge is due to combination of the large calibre with the soft material, the mass, and the relatively low velocity of the projectile. These combine in such a way that the adversary experiences in his body the maximum development of shocking as distinct from penetrative effect. This is just what is wanted in an active service revolver. ”

It is interesting that nearly a hundred years later, this passage remains a good account of the issue, superior to many things written since.

I am well aware some readers will get distracted by the semantics of some of the terminology used.

Perhaps the most significant change since this was written has been the creation of jacketed hollow-point (JHP) ammunition that will feed reliably through an automatic. This has narrowed the gap in terminal effect between large-bore revolvers and large-bore self-loaders.

A .45 round that fails to mushroom will often make a wider wound channel than many 9mm and other medium-calibre rounds that do mushroom. .45s that do mushroom make very big wound channels.

Advances in bullet design intended to improve the performance of light, medium calibre, high-velocity bullets are even better applied to heavy, large-calibre rounds.

Logistics

You may regard logistic considerations over effectiveness.

The most common combat pistol round is the 9mm Luger, also known as the 9 x 19mm or 9mm Parabellum.

The 9mm Luger is the NATO standard pistol round, but its military and civilian use dates back to the 1900s. It was the round of the German, and other armies, for two world wars.

The majority of sub-machine guns are chambered for this round.

There are very few countries in the world where 9mm Luger cannot be found.

The medium-calibre 9 x 19mm is not as effective as the large bore .45, although many try to convince themselves it is.

Mel Tappan considered the 9x19mm round as good for hunting game in the 100-125 lb range (in the absence of a long-arm). Thus, your 9mm backup can be used to forage for small to medium game. Anything wolf-size or smaller.

If you have very small hands, a 9mm model may offer a slimmer grip without compromising magazine size.

Although not the optimum choice for defence, a 9mm handgun is a prudent addition to your survival battery.

Guns like the Berretta M9/92 are too big for roles other than as a primary overt weapon.

As for 45s, a compact or sub-compact model is preferable.

In nations that have received Soviet or Chinese military aid, the 9mm Makarov round, aka 9 x 18mm, may be more readily found than the 9mm Luger.

The 9mm Makarov is designed to be the most potent load that can be accommodated by a light, blowback-action pistol. Velocity and bullet weights are lower than the more powerful 9mm Luger.

The 7.62 x 25mm round may also be common in countries that use Soviet or Chinese weapons.

Most Soviet sub-machine guns, and their Chinese copies, are chambered in this round.

In handguns, it is usually found in the TT33 Tokarev/Type 51/Type 54 and a few other Warsaw Pact designs, such as the Czech vz.52. Some of these weapons are still in use in certain parts of the world.

The round is effectively identical to the 7.63mm Mauser round, so may be encountered in countries where the C96 Mauser “Broomhandle” was popular.

The 7.63mm Mauser/7.62 x 25mm/7.62mm Tokarev is a high-velocity round noted for its high penetration and flat trajectory. The small calibre creates a narrower wound channel than many other combat pistol rounds.

W.E. Fairbairn was familiar with the round from his time with the Shanghai Police. He suggested that the round was more effectively used if aimed at shoulder level, where the high-velocity round was most likely to shatter bones and create secondary missiles.

This is fairly good advice for using any pistol round.

Convenience

Automatics

The gun you have with you will always been more effective than the one you left at home because the latter was inconvenient to carry.

There are some lightweight, low volume automatics in 9mm Luger. The 9mm Luger round requires a locked breech.

Many smaller automatic pistols are simple, blowback weapons and therefore use cartridges other than the 9mm Luger.

If you opt for a pocket automatic, the best choice is a weapon in either .380 ACP or 9mm Makarov.

Pocket pistols in 9mm Makarov are fairly rare, but many duty weapons, like the Makarov PM/Type 59, may be compact enough.

A wider choice will be found in .380 ACP, also known as 9 x 17mm, 9mm Short or 9mm Kurtz.

The .380 is slightly weaker than the 9 x 18mm. Like the Makarov round, it is well suited to small, blowback pistols and is a better choice than smaller calibre options such as the 7.65mm/.32 ACP and 6.35mm/.25 ACP.

Having less energy and momentum than a 9mm Luger or .45 ACP, the mushrooming of hollow-point ammunition in .380 or 9 x 18mm may be less reliable. You may be better off saving your money and loading FMJ that is more likely to have sufficient penetration to reach vital organs.

Revolvers

Many small-frame models of revolver such as the Smith & Wesson J-frames and Colt Detective weigh under a pound, but only have five or six shots.

Small medium-calibre revolvers in .38 Special, .357 Magnum and 9mm Luger are preferable to smaller-calibre weapons in .32 or .22. .32 S&W Short and .32 S&W Long may be used for economical plinking, practise and small-game hunting.

The same size cylinder holds six .32 rounds rather than five .38/.357/9mm. Recoil is reduced and the weapon is easier to control, which may help put rounds where they are wanted. Such chamberings, therefore, may be preferred for those that find 9mm/.38 too much in a lightweight weapon.

Some .32 H&R magnum hollow-point loads seem to have issues with expansion. In absence of more specific information about particular loads, semi-wadcutter or wadcutter loads may be the prudent choice to ensure adequate penetration.

Weapons chambered for 327 Fed. magnum will also fire 32 H&R magnum, and weapons chambered for either round will also fire .32 S&W Short and .32 S&W Long.

The 9mm Luger in a revolver has the edge over the .38 in velocity, but the merit of revolver rounds is that they can use rounds that would not reliably feed through an automatic.

The .38 and .357 cases can be loaded with wide-mouthed, soft, malleable, hollow-points, ideally of 200 gr or more, that are likely to be more effective than any medium-calibre round an automatic can fire.

If fired in an emergency from within a pocket, a pocket revolver has no slide to catch in the pocket lining. For similar reasons, models with concealed or internal hammers are preferable.

Special Purpose

.25 ACP, .32 ACP, .380 ACP, 9 x 18mm and .45 ACP are all subsonic in standard loadings. The smaller rounds are sometimes preferred since they allow the use of a smaller weapon and suppressor.

Most .22 rounds are subsonic when fired from pistols, so are also suited to suppressed applications.

.22 weapons are also useful for target practice or for foraging.

.22 revolvers often offer the option of switching between .22LR and .22 magnum by exchanging cylinders.

Some .22 revolvers can chamber more than six rounds.

Non-Runners

Other than the exceptions already suggested, revolvers are not recommended.

After more than a century of military service, it is finally being accepted that claims that revolvers are more reliable than automatics are more theoretical than practical.

Possibly, only in the instance of a misfire, does a revolver offer an advantage.

This is offset by the greater ease in reloading and the usually larger ammunition capacities of automatics.

For a given calibre, an automatic tends to be lighter and more compact than the equivalent revolver.

You may be adept at quick wheel-gun reloads on the range, but under the stress of real combat it is better to keep dexterous actions as simple as possible.

Rounds such as the much hyped .40 S&W, .375 SIG and 10mm Auto are not recommended.

These are all medium-calibre rounds, most loads trying to emulate the performance of the .357/125 gr. Essentially just faster 9mm Luger.

Unsurprisingly, performance is inferior to the .45.

Logistically, ammunition in these chamberings may be difficult to find outside the US.

The answer is that we need control as well as power.

For many shooters. a quick follow-up shot with a .44 magnum or similar may be difficult.

No round can be guaranteed to always neutralize a threat first hit, or to always hit, for that matter.

Another reason for using the .45 ACP is that most of the loads that exceed the .45 ACP in power are primarily revolver loads.

For many reasons, not least its mass and bulk, the Desert Eagle is not recommended as a defence gun.

The .45 Long Colt and .44 Special are more manageable, but usually found in revolvers, so the .45 ACP remains the best choice.

Both “Attack, Avoid, Survive” and “Survival Weapons” have advice on the use of firearms.

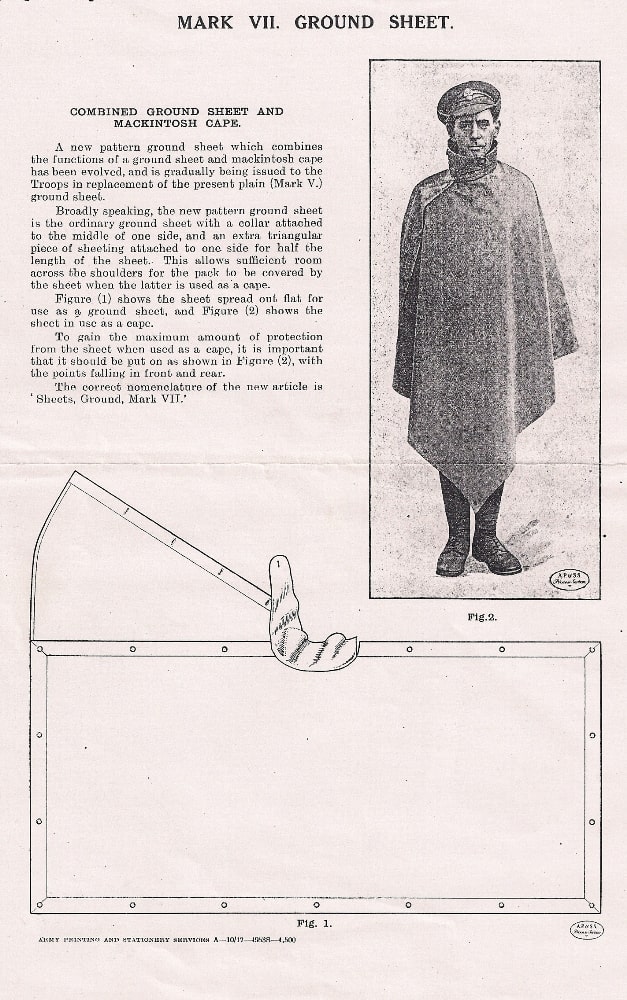

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.

of the 37 pattern small pack were actual clothing. The interior was divided into two compartments, the forward one bisected by an additional divider. One forward pocket held the soldier’s pair of mess-tins, the other a water-bottle. Carried in the main compartment was a groundsheet, towel, soap, pair of spare spare socks, cutlery and possibly an emergency ration and cardigan. Below is a photo of a typical British infantryman’s small pack contents, taken from “British Army Handbook 1939-45” by George Forty.